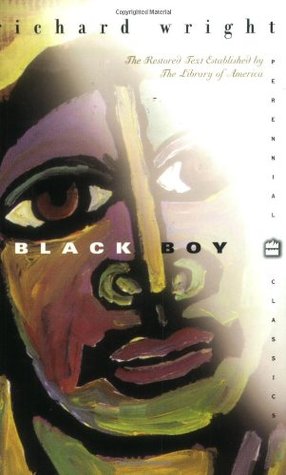

Review: Richard Wright’s “Black Boy”

by Miles Raymer

Recently, the desire arose in me to read something that might help me better understand the internal perspectives of African-Americans and my country’s ignominious legacy of slavery. My mother, who spent a long career teaching American history to undergraduates, recommended Richard Wright’s autobiography, Black Boy. And although I expected the book to be good, I didn’t anticipate how profoundly it would speak to me. Black Boy is a masterpiece of literary genius.

Wright presents his story in two parts. Part One, “Southern Night,” chronicles his upbringing in the deep south during the early 20th century. Part Two, “The Horror and the Glory,” recounts Wright’s experiences after moving to Chicago as a young man in the late 1920s, including his rocky relationship with the Communist Party. The progression is linear, with occasional parenthetical interjections where Wright utilizes his fully-fledged adult mind to reflect on key moments in his personal development. His prose hums with energy and artfulness; haunting and observant passages grace every page.

Wright’s narrative feels basically limitless in its potential for generating insight, but there were three main themes that I kept returning to along the way. The first is Wright’s amazing ability to depict what it feels like to grow up as a member of a disempowered class. His experiences obviously have a particularly African-American flavor, but are also universal enough to speak to anyone who knows (or wants to imagine) what it feels like to struggle against systemic oppression. As a young boy, Wright learns the character of American racism in stages, stemming from his innately inquisitive nature:

I soon made myself a nuisance by asking far too many questions of everybody…It was in this manner that I first stumbled upon the relations between whites and blacks, and what I learned frightened me. Though I had long known that there were people called “white” people, it had never meant anything to me emotionally. I had seen white men and women upon the streets a thousand times, but they had never looked particularly “white.” To me they were merely people like other people, yet somehow strangely different because I had never come in close touch with any of them. (23)

As he grows older, the “strangely different” quality of white people becomes crystallized by Wright’s growing awareness of the brutal and routine acts of violence visited upon black bodies by white ones, as well as the constant threat of violence that permeates the black community. This reality gives birth to fierce imaginings of defending himself against an implacable white aggressor:

My spontaneous fantasies lived in my mind because I felt completely helpless in the face of this threat that might come upon me at any time, and because there did not exist to my knowledge any possible course of action which could have saved me if I had ever been confronted with a white mob. My fantasies were a moral bulwark that enabled me to feel I was keeping my emotional integrity whole, a support that enabled my personality to limp through days lived under the threat of violence.

These fantasies were no longer a reflection of my reaction to white people, they were a part of my living, of my emotional life; they were a culture, a creed, a religion. The hostility of the whites had become so deeply implanted in my mind and feelings that it had lost direct connection with the daily environment in which I lived…I had never in my life been abused by whites, but I had already become as conditioned to their existence as though I had been the victim of a thousand lynchings. (74)

Wright’s struggle to deal with these crippling emotions is compounded by his family’s poverty and strict religious practices, which he reflexively rejects. Years later, as a young man in Chicago, he demonstrates a keen awareness of the damage wrought on the African-American community by the cruelties of history and omnipresent injustice, describing with painful intimacy the total hopelessness that is the logical conclusion for so many of his black brethren:

I was going through a second childhood; a new sense of the limit of the possible was being born in me. What could I dream of that had the barest possibility of coming true? I could think of nothing. And, slowly, it was upon exactly that nothingness that my mind began to dwell, that constant sense of wanting without having, of being hated without reason. A dim notion of what life meant to a Negro in America was coming to consciousness in me, not in terms of external events, lynchings, Jim Crowism, and the endless brutalities, but in terms of crossed-up feeling, of psyche pain. I sensed that Negro life was a sprawling land of unconscious suffering, and there were but few Negroes who knew the meaning of their lives, who could tell their story. (267)

This final sentiment points us to the second theme that cried out to me in Black Boy: The power of the written word to nurture and liberate the human mind, even in the direst of circumstances. Wright’s memories overflow with enlightening descriptions of the sweeping impacts that reading and writing can exert on human life. From the very first time Wright hears a story read aloud by a schoolteacher, he knows intuitively that it is something miraculous:

As her words fell upon my new ears, I endowed them with a reality that welled up from somewhere within me…The tale made the world around me be, throb, live. As she spoke, reality changed, the look of things altered, and the world became peopled with magical presences. My sense of life deepened and the feel of things was different, somehow…My imagination blazed. The sensations the story aroused in me were never to leave me. (39)

Wright’s literary consciousness grows along with his racial consciousness, offering ephemeral but sturdy salvation from the torturous mindsets of oppression. Wright’s love affair with reading becomes a heroic fight for survival, as evidenced by his first encounter with the works of H.L. Mencken:

Why did he write like that? And how did one write like that? I pictured the man as a raging demon, slashing with his pen…What was this? I stood up, trying to realize what reality lay behind the meaning of the words…Yes, this man was fighting, fighting with words. He was using words as a weapon, using them as one would use a club. Could words be weapons? Well, yes, for here they were. Then, maybe, perhaps, I could use them as a weapon? (248)

This stroke of insight––that racial violence might be countered with linguistic violence––transforms Wright, propelling him down a path of self-discovery as he wrestles with his burning desire to give voice to his slice of subjectivity:

I strove to master words, to make them disappear, to make them important by making them new, to make them melt into a rising spiral of emotional stimuli, each greater than the other, each feeding and reinforcing the other, and all ending in an emotional climax that would drench the reader with a sense of a new world. That was the single aim of my living. (280)

Anyone who reads Black Boy will agree that Wright certainly developed the talent to “drench the reader with a sense of a new world,” and it is this vibrant image that brings us to the third theme in this book that I want to address: Wright’s conviction that the United States––a “new world” shockingly abused by its crude “discoverers”––can never be truly whole or fully decent as long as racial animus continues to corrupt American society. At the core of this conviction is the irony of the African-American position in American life:

Whenever I thought about the essential bleakness of black life in America, I knew that Negroes had never been allowed to catch the full spirit of Western Civilization, that they lived somehow in it but not of it. (37)

It is critical to note here that Wright doesn’t reject Western Civilization outright or seek to blame it for the predicament of African-Americans; he is not “anti-American” in that regard. Rather, he laments the evils of exclusion, of forced participation in a sociocultural and political project over which one has no ownership, and the fruits of which are meted out according to such an obviously frail justification as skin color. This problem arises repeatedly in Black Boy, with Wright’s thoughtfulness and urgency taking new life in each iteration:

I feel that for white America to understand the significance of the problem of the Negro will take a bigger and tougher America than any we have yet known. I feel that America’s past is too shallow, her national character too superficially optimistic, her very morality too suffused with color hate for her to accomplish so vast and complex a task. Culturally, the Negro represents a paradox: Though he is an organic part of the nation, he is excluded by the entire tide and direction of American culture. Frankly, it is felt to be right to exclude him, and it is felt to be wrong to admit him freely. Therefore if, within the confines of its present culture, the nation ever seeks to purge itself of its color hate, it will find itself at war with itself, convulsed by a spasm of emotional and moral confusion…Our too-young and too-new America, lusty because it is lonely, aggressive because it is afraid, insists upon seeing the world in terms of good and bad, the holy and the evil, the high and the low, the white and the black; our America is frightened of fact, of history, of processes, of necessity. It hugs the easy way of damning those whom it cannot understand, of excluding those who look different, and it salves its conscience with a self-draped cloak of righteousness. Am I damning my native land? No; for I, too, share these faults of character! (272-3)

This prescient passage shows just how well Wright came to understand America in his time, as well as his willingness to admit his personal frailties as a way of identification with the American ethos. Despite the many positive and substantial points of progress in race relations and law since Wright’s death in 1960, we again find ourselves “convulsed by a spasm of emotional and moral confusion,” again thrown into internecine conflict derived from the embattled and immoral aspects of our national heritage.

What is the remedy? That is for each citizen to decide, and for us to build together at every conceivable site of conversation and debate across this great and sometimes terrible nation. We should look to Wright as an exceptional source of inspiration. He found his voice and his method. He was a champion of the continual and passionate undertaking of the struggle of life, as channeled through the peaks and valleys of language:

I headed toward home alone, really alone now, telling myself that in all the sprawling immensity of our mighty continent the least-known factor of living was the human heart, the least-sought goal of being was a way to live a human life. Perhaps, I thought, out of my tortured feelings I could fling a spark into this darkness…I would hurl words into this darkness and wait for an echo, and if an echo sounded, no matter how faintly, I would send other words to tell, to march, to fight, to create a sense of the hunger for life that gnaws in us all, to keep alive in our hearts a sense of the inexpressibly human. (383-4)

Rating: 10/10