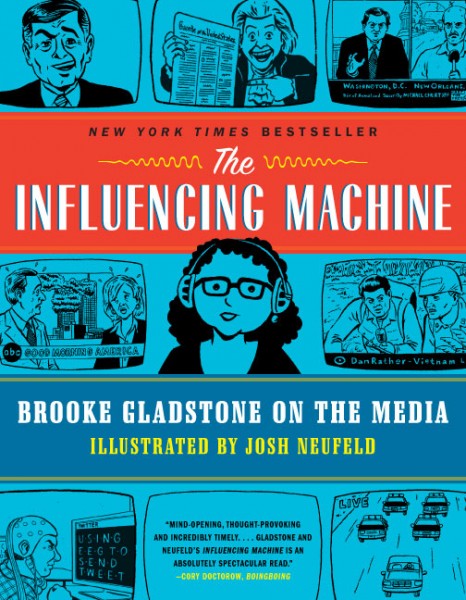

Book Review: Brooke Gladstone and Josh Neufeld’s “The Influencing Machine”

by Miles Raymer

This is a terrific primer on media history and one reporter’s take on how average citizens can promote a free, open news environment. Aided by Josh Neufeld’s clever illustrations, Brooke Gladstone takes the reader on a whirlwind journey through media history’s most tenuous moments, setting her sights on the perennial conflict between authoritarian power, which has traditionally sought to suppress non-propagandist news, and the heroic but flawed individuals and organizations who have fought the long struggle for a free and protected press. Though she doesn’t delve deeply into any single topic, Gladstone offers an eclectic set of perspectives that sift the right questions from a broad range of sources rather than perpetuating the illusion that any single source has the right answers.

Its comic book aesthetic and simple language make this text accessible to all kinds of readers; it’s a great potential resource for junior high and high school history and language arts teachers. Gladstone provides a handy list of media biases and an overview of psychological biases as understood by contemporary social scientists and neuroscientists. She doesn’t shy away from the reality that figuring out who to trust is no cakewalk, especially when the biggest potential deceiver is your own brain.

At the heart of Gladstone’s message is her desire to switch out one cultural metaphor for another. She claims that most people think of the news media as an “influencing machine” that alters (and to some extent controls) the minds of consumers. This machine is variously portrayed as a means of population control for shadowy cabals with aspirations of world domination, corrupt governments, or super-wealthy elitists eager to propagate their personal worldviews. Gladstone rejects this metaphor, arguing instead that the media is better understood as a mirror, one that reflects and amplifies the virtues and flaws of its consumers. She makes the case that media distributors, even ones that seem indestructible, are ultimately subject to the preferences of their audience: us. Citizens should take up the responsibility of learning about and interacting with valuable media sources and reject those that pander to the lowest common denominator.

I generally agree with Gladstone’s views and think the mirror metaphor is a useful way of talking about the media’s role in a free society. However, I think the media can be understood as both an influencing machine and a mirror, depending on context. I certainly don’t think the mirror metaphor applies to autocratic regimes where the government has complete control over the news cycle (e.g. North Korea). And closer to home, it’s hard to argue that the personal preferences of powerful media executives don’t exert a disproportionate influence on public policy.

We can’t ignore the potential for private media companies to become so large and influential that they can buy government influence and/or begin breaking down the barrier between service providers and content producers. If your cable/internet provider is also your primary content producer (or can favor certain content providers over others), and there is not viable competition from other providers (as is currently the case in most of the US), it becomes increasingly difficult for users to make the bottom-up consumption choices for which Gladstone advocates. This is the crux of the ongoing net neutrality debate, and it’s unclear if Gladstone’s call for informed media consumption would have the same harnessing effect on media companies operating in a post-net neutrality world. Another source of anxiety is the question of how media freedom changes in the face of the US government’s recent hostility toward whistle-blowers. There are future scenarios in which the influencing machine shatters the societal mirror.

Overall, Gladstone and Neufeld aptly highlight our simplest and most useful modes of media analysis. The Influencing Machine has no pretensions of being more than it is. What it lacks in depth it makes up in accessibility and historical scope. Its message––that the power to enact progress resides less in the machinations of institutions and social networks than in everyday choices made by common people––is timely and true. True enough, anyway.

Rating: 7/10