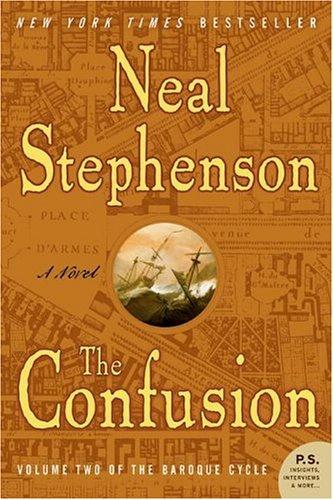

Book Review: Neal Stephenson’s “The Confusion”

by Miles Raymer

Deeper into the wordy quagmire that is Neal Stephenson’s Baroque Cycle. As with Quicksilver, this volume contains a considerable dose of magical moments dissolved in a nearly impenetrable sea of overdone gibberish. It’s brilliant gibberish, but not brilliant enough to make this book shine the way I typically expect from Stephenson. While enhancing the Baroque Cycle’s thematic strengths and moving the saga forward in promising ways, The Confusion is ultimately every bit as languorous as Quicksilver.

This volume neglects the Baroque Cycle’s most interesting plot thread––Stephenson’s fictionalized account of the intellectual development and personal squabbles of 17th century Europe’s Enlightenment figures––for nearly 500 pages. Daniel Waterhouse is the most maligned victim of Stephenson’s overreach. Save a decidedly moving scene in which he brings a floundering Isaac Newton to his senses, Daniel’s narrative is largely put on hold here.

Our consolation is that the lives of Jack Shaftoe and Eliza of Qwghlm become more complex (if not always more interesting). These two signify the social upheaval and economic recalibration that swept through Europe (and the rest of the world, to varying extents) as the 17th century came to a close. They are the figureheads of Confusion, that great handmaiden of Progress.

Jack Shaftoe, it turns out, is not dead. His body having purged itself of the maddening French Pox, Jack teams up with an eclectic cabal of similarly disenfranchised galley slaves to win their freedom. The antics of this motley bunch are variously inspiring, puzzling, and yawn-inducing. During the decade leading up to 1700, they gallivant through Barbary, the Middle East, “Hindoostan,” the Far East, and the New World, before returning to Europe. Along the way, they manage to steal a boatload of “magic gold,” which enhances Jack’s already considerable mystique as Europe’s most audacious rapscallion. Jack solidifies his reputation as a ruthless pragmatist, and his diverse gang of freedom-seekers serves as Stephenson’s metaphorical conduit for inserting a modern sense of self-determination into a thoroughly antiquated historical setting. As a general idea, it’s clever and fun. Jack is charismatic and exhibits just enough moral complexity to pique my curiosity about how his unfolding odyssey will terminate. Unfortunately, his story is cluttered with bizarre, boring adventures that rarely influence the Baroque Cycle’s overarching plot. Important events do happen, but slowly, ever so slowly.

Eliza has grown on me. I wasn’t sure how I felt about her after Quicksilver, but I think it’s fair to say she propounds a strange sort of feminism after all, and isn’t quite the bimbo with brains I thought she was. Similar to Jack, she is a vehicle for unlikely (but inevitable) fits of progress in a stifling world. She is unusually assertive and laudably subversive, but also tragically subject to the confines of Baroque gender roles. Her most intriguing quality is her relationship with the French aristocracy, which turns up its nose at her humble origins but can’t deny her intellectual cunning and financial savvy. Despite her past, Eliza is eventually declared a Duchess by Louis XIV––a historically significant concession that marks the decline of monarchic power and the rise of the mercantile class and free markets. Later, she marries (unhappily) into a very powerful French family. Though Eliza is forced to assume traditional wifely responsibilities, she retains her passion for independence, her economic acuity, and her steadfast hatred of the slave trade. She is a woman of contradictions sprung from traits and perspectives ahead of her time. Unfortunately, as with Jack’s tale, Eliza’s story is tarnished by Stephenson’s inability to quell his discursive predilections. Ideas that could be communicated in a few carefully-chosen scenes get lost in a barrage of monetary minutiae, epistolary doldrums, and tiresome aristocratic bickering.

Perhaps the saddest aspect of both Eliza and Jack is that they seem more coherent when understood as symbols rather than as actual people, a quality that makes for excellent intellectual fodder but prevents me from making an emotional commitment to them.

The farther I fall down the Baroque Cycle’s rabbit hole, the more I find myself begrudgingly enthralled by the project’s scope, if not its nuts and bolts. Perhaps I am just desperate to justify my efforts after 1,700+ pages, with nearly 900 left to go. I’ll stand by my claim that it’s far from Stephenson’s best work, but I’m beginning to doubt that I will get to the end and feel I’ve wasted my time. Despite its flaws, The Confusion concludes with a series of highly entertaining and genuinely meaningful flourishes, mostly having to do with Jack’s return to England. Perhaps it’s not too much to hope it all might come together in a climax most marvelous, one befitting Stephenson’s ambitions and undeniable genius.

Rating: 5/10