Journal #48: Circling America, Pt. 3

by Miles Raymer

Readers who’ve come this far might justifiably be thinking: Yeah, America’s a nice place and all, but six weeks on the road couldn’t have been pure bliss! Where’s the dirt? Our trip was surprisingly devoid of setbacks (no car trouble, natural disasters, relationship-altering fights, etc.), but it definitely wasn’t a perfect pleasure all the time.

Part Three: The Squalor

America is home to a lot of strife. Myriad socioeconomic and political problems threaten the prosperity of our individuals and communities. And while touring the National Parks pulled a rosy veil over the landscape, only someone completely blind to America’s internal struggles could have failed to notice the telltale signs of suffering and decay.

The Walmart Effect

Our first encounter with America’s darker self came early on, in Omak, WA––Jessie’s birthplace. Omak is just one of countless rural communities across the country degraded by the “Walmart Effect.” The dynamic of the Walmart Effect isn’t hard to understand (there’s even a whole book about it): Walmart opens a new megastore, undercutting local businesses by offering lower prices on almost all consumer goods. Eventually, local shops begin closing because they can’t compete; local wages also drop. Main Street starts to look like Skid Row, and Walmart rakes in profits. Numerous fast food restaurants and retails chains––also not local––ride in Walmart’s wake.

The Walmart Effect is not without its perks––namely its very low prices and some new jobs––but Omak looks very different today than when Jessie visited during summer vacations growing up. Roughly two-thirds of the local businesses she can remember are now boarded up, and the town feels distinctly less vibrant.

Jessie’s mother, Dee, has worked at Walmart for more than two decades, and didn’t have many nice things to say about the working conditions. She recently suffered a back injury on the job, and hasn’t had an easy time getting the care she needs. She worries that the managers will do everything they can to get rid of her now, because she’s an older employee who can’t do the same physical work she used to, and also has a small benefits package they’d rather not pay for.

As an outside observer, Dee’s anecdotes confirmed the general sentiment I’ve encountered elsewhere: Walmart is a heartless, profit-obsessed company that cares little for its employees or their communities.

Thousands of miles from Omak, I snapped a picture at a shopping center in Maine. I’m not sure how the corporate execs managed to let this perfect representation of the Walmart Effect remain in the open air, but my photo stands as proof that Walmart does occasionally (if indirectly) cop to the results of its business practices:

Underpaid Educators

Walmart employees are far from the only Americans struggling to get by. At a Cabela’s in South Dakota, a friendly checker struck up a discussion with us as she rang up our canister of camping fuel. She figured we were from out of town, and wanted to know what we were doing for vacation. When we said we were on a six-week road trip, she was amazed we could afford to take six weeks off work. I explained that I was unemployed and that Jessie was a teacher, and then things got interesting.

It turned out this woman––probably in her late fifties or early sixties––had recently retired from a career teaching first grade. She said she’d always had at least one additional job, working weekends during the school year. She’d go to work Sundays, then head to her classroom and prep late into the night. During summers, she couldn’t support herself without taking on more hours at her weekend job, leaving little time for vacation. South Dakota, she claimed, was dead last in teacher pay compared to other states (according to the NEA, South Dakota was second to last in terms of starting teacher salary as of the 2012-2013 school year).

The woman didn’t speak bitterly, and gave the humble impression that complaining about her situation would have felt shameful. But as Californians who’d never heard of teachers having to work multiple jobs, Jessie and I were flabbergasted and angry on her behalf. I was ashamed that I’d never realized how difficult it can be for teachers to make ends meet in lower-paying states.

Flagged Down

As a Californian, I’ve watched with removed fascination as the recent Charleston shootings brought attention to the prominence of the Confederate Flag in the American South. Before this event, I had no idea that, as of June, the flag was still flown in several southern state capitols. I assumed those who flew the flag from their front porches or car windows were few and far between, taken seriously only by ignorant hate groups.

By July, I knew better. So I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised when, as we descended the Great Smoky Mountains, Jessie and I noticed a big truck behind us with a Confederate Flag license plate. I should be clear––this truck didn’t tailgate us, nor did the driver act discourteously in any fashion. But still, Jessie and I felt uncomfortable. I found myself thinking: If this makes us––a straight white couple––nervous, how would it feel for a biracial couple, a black couple, a gay black couple, or any of the other permutations of American couples who should be able to drive anywhere in America and feel safe?

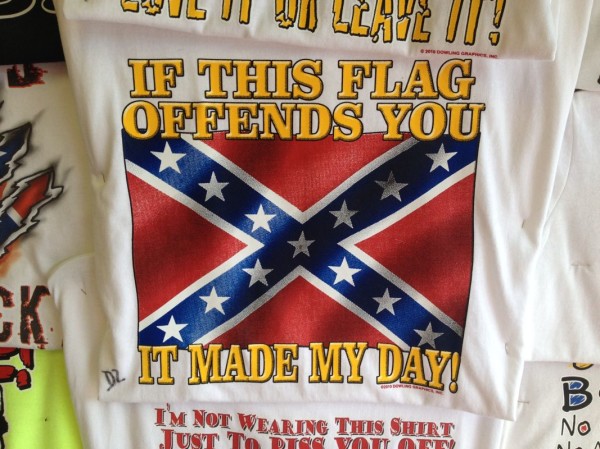

Little did we know, our unease would only increase as we rolled into Gatlinburg, TN. A rural town at the base of the Great Smoky Mountains, Gatlinburg is hands down the most repulsive place I’ve seen in America. Even if you don’t mind the Parkway crammed with tacky gift shops and paranormal-themed amusement parks, the place is a hotbed of hate dressed up as a tourist glitzfest. Here’s a sampling of what we found there:

I’ll cop to being an intolerant jerk in this instance. Almost everywhere we went on our trip, I did my best to accept the places and people on their own terms. By and large, I found Americans from all regions to be kind and courteous folk, and the inhabitants of Gatlinburg were no exception. But the town itself is a stain on our democracy, one that makes my blood boil. I wish we could scoop it out of the earth and hurl it into the deepest part of the Atlantic Ocean.

Meet Our (Not So) New Corporate Overlords

My experience of Nashville was a lot tamer, but still somewhat disquieting. Nashville’s old downtown is in great condition, with its vintage brick buildings, classic bars, restaurants, and shops. Even in the sweltering 100+ degree heat, I happily soaked up the live country music humming through the air as we strolled past joints with quirky displays and strange names.

What this picture doesn’t show is the towering behemoth that has been leering down on the festivities for more than two decades now.

Have you ever seen a building that so bluntly embodied the unsavory character of its corporate namesake? I can see the designers in the meeting room now:

“You know what would give this skyscraper just a little more kick, Jim?”

“What?”

“Horns!”

“You mean, uh, like, devil horns?”

“Yeah, it’ll be great for our public image!”

Even if AT&T weren’t one of the most reviled companies in the country, this monstrosity would still look like a ravenous beast desperate to monopolize every tech commodity in its path. It’s a blight on the otherwise endearing Nashville skyline.

Corporate mega-structures are even more upsetting when contrasted with America’s many dilapidated neighborhoods, like this one near the Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis:

Cadillac Stench

Things often fall apart because of natural attrition or lack of resources for upkeep, but sometimes the process is driven by good, old-fashioned human idiocy. So it has been with Cadillac Ranch in Amarillo, TX. Cadillac Ranch has four decades of rich cultural history, and is an interesting example of audience participation in a piece of public art. But what started out as a colorful experiment has turned into a smelly, trash-strewn cesspool.

When we visited, almost all the cars were surrounded by pools of fetid water, with hundreds of discarded spray paint cans and other detritus making it nearly impossible to walk up to a car without wading through trash. This was especially galling in light of the two large dumpsters (mostly empty) standing by the highway right next to the installation. Cadillac Ranch may have been a captivating and unique landmark at one point, but now it’s little more than a junkyard.

Desert Reservoir

While growing up in central California, some of Jessie’s classmates would spend weekends at a seemingly paradisiacal vacation destination she never got to visit. Recalling stories of fishing and water recreation at the beautiful Lake Havasu, Jessie decided the tail end of our trip would be a good opportunity to see what all the fuss was about.

Lake Havasu is an artificial reservoir on the Colorado River, where it delineates the border between southern California and Arizona. The Parker Dam, built in the 1930s, created the large reservoir that now feeds two major aqueducts.

It was an impressive feat of engineering for its time, meant to extend the boundaries of human life and create economic opportunities. But in light of the West’s recent drought, and the promise of more to come as the climate warms, I don’t think this reservoir and others like it represent a sustainable way of life. I’m not opposed to dams and reservoir systems in all contexts, but some places are better left alone. Simply put, Lake Havasu is ugly. The lake is ugly, and the city––rife with strip malls and fast food joints––is even uglier. We left thinking best course of action would be for humans to withdraw from this environment and let the desert reclaim it.

After seeing Lake Havasu for herself, Jessie suddenly wasn’t jealous of her former schoolmates anymore

Conclusion: Circling, Inside and Out

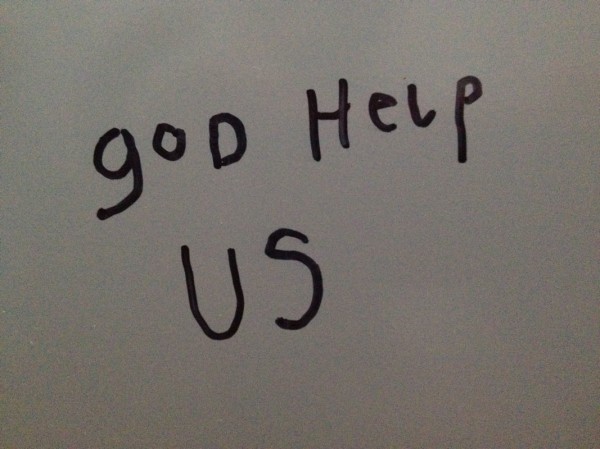

Having experienced new glimpses of a vast country filled with people, splendor, and squalor, it’s hard to know exactly what I brought home with me. It’s probably one of those questions I won’t be able to really answer until late in life––if then. Some days, I thought my heart would burst with the joy I felt traversing this land; other days, I identified more with this supplication, scrawled in a restaurant bathroom stall by an anonymous resident of Riverside, CA:

While I don’t believe there’s anything out there to hear that cry, I understand the impulse to beg the universe for mercy in the face of the unknown. The truth about living in America––or anywhere, for that matter––is that we are constantly bearing witness to something we’ll never truly understand. We observe, contemplate, and guess, but rarely comprehend. And since we are ignorant, our illusions of ownership are shabby. No one has any right to this land or the fabulous things that thrive here. We must all earn our place.

Never was this more evident than on our first night in Acadia National Park, when I found myself unable to sleep despite being tucked away in our cozy tent, Jessie breathing peacefully beside me. In that quiet dark so far from home, all my past selves seemed to crowd in around me, bringing the suffocating howl of a body trying to grasp its origins and possible futures. The noncommittal rain sounded out my regrets, questions, hopes, lies I tell myself and others. And the Great Lie, the one that tells us there’s a secret core to everything––a nugget of purest essence we can unearth if we just dig hard and fast enough.

By rejecting that Lie, I realized that in circling America, I was also circling myself.

Road trips aren’t just about figuring out where we are, but who we are. Which contours can be ruffled into new fertility? What regions go undiscovered? And with each new circumscription of land and body, do we really learn anything, or just touch for a moment the things we’ll never know?

Fearing these questions might swallow me up, I was relieved when Jessie stirred. She knew something was up. She always does. So we talked, and she brought me back––slowed the spinning and anchored my dizzy mind.

Finally, I slept. Dawn came. We moved on, leaving pieces of past selves scattered by the highway, or shoved into bear-proof trashcans.

Nice article. You remind me again how grateful I am to no longer be living in Tennessee, Georgia, or Kansas, lol. When I read about your travels and ponderings, I can’t help but think that just as a softball team’s greatness or slothness is made up of its aggregates w/ their own unique skills and behaviors, each of our experiences in life locked into particular moments of space and time make up who we are in the present. Peel away the aggregates and we dissolve into nothing. I suppose where each of us will be in the future depends on what parts we add now. It’s interesting to me to think about the whole series of twists and turns we go through before reaching that final, windy last stop. I am glad after all your twists and turns you made it back to Humboldt safe and sound:) I can only wonder where I culture will one day end up when all its aggregates are accounted for.

That’s an interesting way of putting it, Barnaby. I think it’s definitely true that our thoughts/experiences simmer around in us as we move through life, prodding us toward some futures and away from others. I sometimes find it frustrating that the process is so opaque. I understand so little about the world around me, but also must admit that I don’t understand much of what happens in my own head! It’s difficult to swallow sometimes, but it’s all part of the great mystery of being self-aware. What a wild ride.

I imagine there are very few people who have seen so much of this country so quickly and with such depth. Good, bad, and ugly, this is an interesting place to be for sure. And it’s easy to start thinking that “America” is pretty much like the three or four cities/towns you know best. This is a very good reminder at just how untrue that is.

I think a lot about the idea of a country as an “imagined community.” While there are some great things that hold us together. it’s also a pure fantasy that we have as much in common as Americans as the myth of nationalism teaches us.

Thank you for sharing your insights from this journey. I feel lucky to have witnessed a slice of loop through you!

I have lived in Ellsworth, Maine, where your photograph of the Downeast Crossing sign (Myrick street) was posted.

The idea for Myrick Street was that it would eventually be built into a large plaza. (There is a Home Depot that predates the Walmart there, and there is a bank, a cell phone store, and a liquor store near the end).

I believe the reason it wasn’t built up, though, was that the whole thing sits on wetlands and there is a strong sentiment that preserving the wetland is important and perhaps allowing the Walmart and Home Depot to be built there was a mistake.

Hi William! Thanks for your comment and for reading my article. It’s great to know that some of the development was stopped in order to preserve the wetlands, and not because Walmart out-competed everything else. The details of this particular situation do somewhat contradict my general point about the Walmart Effect, but I still think the sign serves as a nice metaphor for Walmart’s business model and practices.