Traveling in Post-Brexit Britain

by Miles Raymer

Introduction: Waves Across the Pond

I can’t remember a time when the political coverage of Britain in the United States was more fervent than during this summer’s Brexit vote. Given the parallels between the Brexit movement and the rise of Donald Trump, it makes sense that many interpreted the referendum as a testing ground not only for the ideas propounded by Trump and his British counterparts (most notably Nigel Farage and Boris Johnson), but also for the bullish and deceitful strategies they use to push their agendas. Now that the results are in, the immediate consequence for Americans is that we can no longer say it is impossible for these ideas and strategies to win a national vote; we must adjust our political calculations accordingly as we scrutinize our upcoming presidential election.

Taking a longer view, it will serve us well to wonder why these movements have arisen on both sides of the Atlantic and how they will affect the political futures of America and its sire state. Many political and intellectual elites seem baffled by the strength of support for Brexit and Trump, but there is now no way to deny that significant support exists (if Trump’s nomination for the Republican ticket wasn’t enough). The reasons for and sources of this support have already been well documented and will continue to be analyzed, so I need not belabor them here. I want to do something smaller.

When Jessie and I began planning our honeymoon late last year, we’d never heard the word “Brexit” and had no idea a referendum on EU membership was on the horizon in Britain. We decided to travel to the UK to visit friends and see more of the beautiful cities and landscapes we remembered from previous trips to that region. When we learned the results of the vote in late June, I had a mixed reaction. I was disappointed because my politics favored the remain voters, but I was also selfishly excited by the success of Brexit. One reason was that my US dollar was suddenly going to do a lot more work for me abroad, but the more important reason was that I relished the opportunity to speak directly with people living in post-Brexit Britain. Americans have heard a lot about what people think in the wake of the referendum, but we don’t get an equal chance to experience how it feels to be a UK citizen pondering the political future. That is the purpose of this article.

Part One: England

Let’s begin in London, where we spent our first bleary day before hopping on a train to the countryside. Our London hosts were Henry and Emily, a delightful couple that befriended me during my year with the JET Programme in Japan. Henry and Emily generously offered their spare room to Jessie and me for a day while we recovered from jet lag, and then for an additional week during the last leg of our trip. Their flat in Hammersmith Borough is clean and cozy, an ideal space for two people with just enough room to accommodate visitors. Jessie and I were charmed by their tiny refrigerator and washing machine disguised to look like a kitchen cupboard––features that mirrored the compactness and energy efficiency we’d experienced in Japanese apartments.

Although both still in their twenties, Henry and Emily are the most cosmopolitan millennial couple I’ve met. They’ve traveled extensively in Europe and Asia, working and living in communities large and small, rich and poor, rural and urban. They never fail to squeeze as much experience as possible into each journey (exploring Japan with them was always fun, but always exhausting!). As upper-middle class Londoners with good jobs, successful families, and an internationalist worldview, Henry and Emily fit snugly with the majority of a city that roundly rejected Brexit.

That first day, Henry and Emily shared their thoughts with us on a walk through beautiful Holland Park. While they both expressed concerns about what Brexit would mean for the future of British politics and economics, they also revealed something more interesting about how voters make decisions. Emily acknowledged that the decision was more emotional and values-based for her, and that she knew Henry was more informed about the details of what Brexit might entail, especially economically. Emily works for a national charity and was raised to believe that cooperation and compassion are the cornerstones of progress; she saw continued participation in the EU as the more cooperative and compassionate solution. Henry, who works at a law firm that specializes in family wealth management, was sympathetic to some of the economic arguments of Brexit supporters, but preferred to vote remain because he thinks the economic benefits of involvement ultimately outweigh the drawbacks. Both made convincing cases for their differing ways of reaching the same conclusion.

Henry and Emily also highlighted an important lesson about the demographics of self-selection, which increasingly influence politics in America and other ideologically-polarized nations. They aren’t close with anyone who voted for Brexit, and are hardly even acquainted with anyone who did (the best example they could think of was one of Henry’s old girlfriends from his teen years). They were shocked by the results of the referendum––shocked not that their fellow countrymen and -women disagreed with them, but by the magnitude of the distance between their personal views and those of Brexit supporters.

We observed this sense of shock in rural Britain as well. Thorney is a serene, tiny hamlet nestled in the heart of southwest England’s Somerset County. Since first traveling there 15 years ago, I’ve described it to people as “The Hobbiton of Britain” (it even has a “One Tree Hill” that looks exactly as I’d imagined Bag End as a child). It is a green place where people live slowly and well, an expansive neighborhood where each home has its own special name, such as Old Withy Yard, Faerie’s Nest, and The Anchorage.

Willow Cottage––the home of Michael and Utta, our hosts––is just off the narrow, hedged-in road that wends through Thorney. The house is better known to my family as “The Hotel Brown”; due to a longstanding friendship between Michael and Utta and my parents, it has been a place of respite for traveling Raymers since the 1970s.

The residents of Thorney exude a durable dignity that isn’t likely to crumble in the face of a single referendum. Still, Michael and Utta were shaken by the Brexit results. They spoke candidly with us regarding their surprise that not only had Brexit passed nationally, but also that three of the four regions of Somerset had voted in favor of it. Micheal recalled hearing from his local poll station that voter turnout had been huge, which he assumed would mean an overwhelming victory for the remain vote. He expected many farmers in the region to vote remain due to the financial help many farmers receive from EU membership, but in the end the leave vote held significantly more sway in rural communities throughout the UK (excluding Scotland, where not a single region voted to leave).

This contentious outcome became vivid for me when I glimpsed a “Vote Leave!” sign amidst a sea of cornstalks on the road to Bath. Two days later, I sat riveted at a livestream of Richard III from London’s Almeida Theatre, which we viewed in the comfort of a local cinema. These lines from Richmond’s closing speech landed with particular bitterness:

England hath long been mad, and scarr’d herself;

The brother blindly shed the brother’s blood,

The father rashly slaughter’d his own son,

The son, compell’d, been butcher to the sire…

Abate the edge of traitors, gracious Lord,

That would reduce these bloody days again,

And make poor England weep in streams of blood! (V.v.24-7, 36-8)

First-worlders can be glad to no longer experience political upheaval in such violent terms, but we cannot deny the fresh metaphorical relevance of Shakespeare’s words. As avid travelers with an adult son raising a family in Australia, Michael and Utta’s perspective expands far beyond Somerset’s horizon; their strong sense of British identity is tempered by numerous friends and family in Europe and elsewhere. The thought of pulling away from that global village gives them pause, although they remain optimistic that the UK will find its way as a sovereign entity and key player in modern economies.

Part Two: Wales

After a week of relaxation, local sightseeing, and stimulating conversation at The Hotel Brown, Jessie and I headed north to Wales. The land retained its bucolic atmosphere while also becoming wilder and more hilly. Our destination was Upper Pant Farm in Abergavenny, a small town just a few miles from Wales’s eastern border with England. Upper Pant Farm is where my friend Josh grew up, and I was eager to see his place of origin. Josh’s parents, Chris and Tessa, live on the farm and raise livestock (mostly cattle these days).

Tessa and Chris seem like people who became farmers because they wanted to distance themselves from everything that makes Brexit so relevant: the globalized economy, nationalistic sentiment, and modern forms of labor that pull humans away from our earthy origins. In some cases, it would be safe to assume that people like this just don’t want to deal with how complicated the world has become. But appearances can be deceiving; Chris and Tessa are both well-educated and informed about national and international events, and each spoke eloquently about any topic I could think to toss their way.

Regarding Brexit, Chris and Tessa drove home the idea that many communities don’t take enough responsibility for themselves. People are eager to blame others for their problems––the government, immigrants, corporations––but they rarely step up to improve their lot in a substantive way. Chris spoke of his involvement in the Abergavenny farming community over nearly three decades, of the various ideas and movements that had come and gone, some leaving lasting impressions, and others falling by the wayside. His emphasis was not on the success of individual projects, but on the process that a community continually undertakes in order to sustain and develop its own style of flourishing. Compared to this process, which lives off the sweat and energetic creativity of small but hardy groups of neighbors, Brexit seems abstract, and even irrelevant to some degree. My Humboldt heart was ravenous for such talk, which resonated deeply with my own motivations for moving back home after my year in Japan.

Jessie and I soon learned that Upper Pant Farm was brimming with perspective. Kit, one of Chris and Tessa’s three sons, visited us for an evening. Kit got married a few weeks before we did, and lives with his wife in Bristol. He’s a jovial and keen fellow who works as an electrician. The job has given him insight into the world of “little-c” British conservatism. Many of Kit’s coworkers and clients are intensely dedicated to their quotidian habits, so their judgments and assumptions flow from their ability to maintain their feeling of normality. They also tend to occupy the under-educated and less wealthy ranks of society. Kit’s interactions with these folks haven’t led him to agree with their politics, but they do give him a richer understanding of why many Brits support Brexit.

Kit also pointed out the problem of people not really knowing what they were voting for, and not just because they may have misunderstood the purpose or implications of the referendum. The UK’s new deal with the Eurozone is still up in the air more than two months after the vote, and your average Brexit supporter will have precious little negotiating power when it comes to deciding how the deal gets done. Ironically, this was a central complaint that the Brexit movement leveled at remain supporters during the campaign.

We also spoke at length with Tina, Tessa’s niece. Tina lives in Germany with her husband and young son, and plays french horn in a police band (a band that does community outreach through music on behalf of the police). As I’ve come to expect from Germans encountered abroad, Tina’s English was impeccable and her argumentation solid. She said that most Germans found the Brexit results shocking. She explained that contemporary Germans see themselves as inextricably part of a larger whole, and don’t take seriously the notion of opting out of the collective arrangement. Tina agreed that the UK’s island geography might make it easier for Britain to see itself as separable from the Eurozone, but also pointed out that such boundaries mean less and less as the global economy continues to reshape the modern world’s borders––virtual, metaphorical, and physical.

When I asked Tina about Germany’s heated immigration debate, she said people are conflicted. Tina supports the compassionate use of German wealth to aid desperate people in need. But she also cannot deny the experiential and ideological chasms between 21st-century Germans and many of the refugees that now reside in Germany. Germans are eager to help, but there is also plenty of anxiety about what role refugees from the Middle-East will play in German society, now and in the future.

Part Three: Scotland

After several days of great food and company, we continued north to Scotland. Scotland was the visual crown jewel of our honeymoon. Its breathtaking landscapes and friendly inhabitants made it a terrific place to spend five days alone as newlyweds.

We didn’t speak to any Scottish folks about Brexit, but we did encounter a peaceful protest one morning in Glasgow:

This march shows the residual drama from Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum. In that referendum, those who voted to remain in the UK were also voting for continued membership in the EU. Since not a single region of Scotland voted in favor of Brexit, we can assume a majority of Scots were happy with their decision from two years ago. These lively protestors were calling for a second Scottish referendum, which would provide another opportunity to leave the UK and freedom for Scotland to autonomously re-negotiate EU membership thereafter. It was moving to see these people showing their national pride, even if the country as whole still may not support Scottish independence. As an American, I was also happy to see the Scottish police handling the march with professionalism and a conspicuous dearth of military-grade weapons.

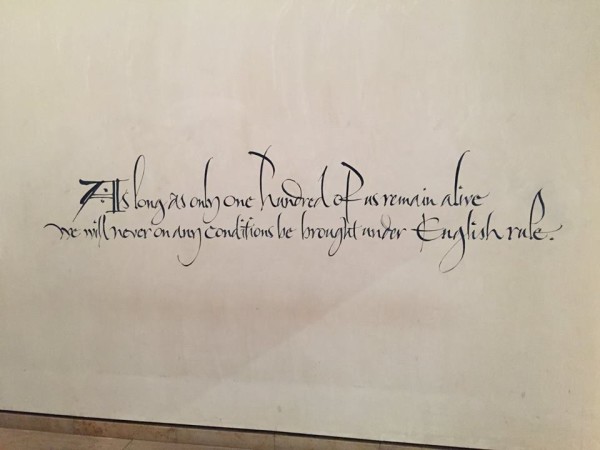

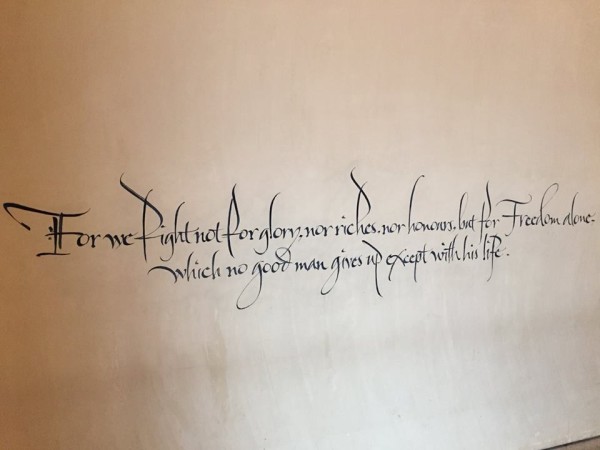

One day later, a visit to the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh reminded me again of Scotland’s long tradition of national struggle:

Part Four: England Revisited

We enjoyed Scotland’s cities, countryside, and citizens immensely, but soon it was time to head back to London for the final week of our trip. We hit a lot of the usual sites for tourists, but I also had the opportunity to spend some quality time with Jon, my closest friend from my year in Japan. Jon and I found each other at orientation in Tokyo, and I distinctly remember the relief I felt when I learned that this clever, witty redhead would not only be working the same job, but would also be living in the same apartment complex.

Jon and I have remained close over the last few years as he’s moved on to exciting jobs in mainland China and now Hong Kong. He’s also the creator of a terrific geopolitics blog called PoliAtlas, which I can’t recommend highly enough (full disclosure: I am his style editor/proofreader). Jon and I have an ongoing discussion about international politics, and it was a rare pleasure to keep it going face to face.

Like everyone else I spoke to on the journey, Jon did not support Brexit. However, he has several friends who voted to leave, and I found it quite telling that they asked him to keep their identities confidential. It speaks to just how divided British society is, both in terms of its political views and its acceptance of difference across social strata. Jon is sympathetic to those skeptical of the immediate prospects of the Eurozone, but like Henry and Emily, he ultimately sees more value in continued involvement in collective endeavors.

Jon also thinks that, despite recent difficulties, citizens in Europe and the UK should remember to be proud of the features that have made and continue to make Europe a desirable place to live: secular, democratic governments; legal protections for individuals (including nondiscrimination laws); vibrant, diverse cultures with long histories; regulations designed to support public safety and health; publicly-funded education and scientific inquiry; and freedom of expression and movement. It can be easy to forget that billions of people across the globe do not have the luxury of taking these things for granted.

Conclusion: The Skies of Abergavenny

During our days in Abergavenny, the sky was a constant delight. Clouds came and went with remarkable alacrity, sometimes dropping sheets of rain and sometimes just shading the landscape. The summer sunlight was always fleeting, and therefore always precious.

One evening, Kit walked us up a nearby hill that overlooked the town. We arrived in time to catch one of the most beautiful sunsets I’ve ever seen:

This natural chiaroscuro reflects humanity’s efforts to know itself, to parse its own actions and respond with something that might be called “better” than what came before. The challenge is that the landscape of life is illuminated differently for everyone; we are all standing in different positions at different times, and the clouds that hinder our sight or pull back to reveal marvelous details are always in motion. This dynamic can make it infuriating to be human, but it also breathes vitality into the scope of human perspective.

Regardless of political views or personal backgrounds, I believe that each UK citizen who cast a vote on June 23rd was attempting to play some small but not insignificant role in human progress. It is a sign of arrogance to assume that no light falls where we cannot see it, and we must listen to those who see light where we see only darkness. That is what I learned from the skies of Abergavenny.

as usual, beautiful conclusion.

Thanks for reading, Dad!

Nicely written, Miles. I especially like what Jon had to say about Europe still being an admirable place to live. Sometimes when we are facing the unknown, as we all are with the fallout from Brexit, we forget what we still have! I very much enjoyed reading this!

beautiful conclusion, Miles. How do I subscribe? Found your website by way of goodreads review of sacred economics by charles eisenstein.

Hi Jonathan! Thanks very much for reading my work, and for the kind words. I don’t actually have a subscribe function for words&dirt, but I may look into it (you are the first reader to ever inquire about subscribing!).

In the mean time, feel free to send me a friend request on Facebook, if you use it. I post everything I publish on words&dirt to my FB profile, so that would be an easy way to follow me. I’ll let you know if/when I get a subscribe function set up.

Thanks again!

You can add me to that subscribe function list, Miles, although I will follow your Facebook profile. I love your writing.

Thank you for reading! I really appreciate it. I will be sure to let you know if/when I get around to configuring that subscribe function.

Hi! Just thought I should drop a note to say I really enjoyed reading this post, especially the conclusion. Coincidentally, I also found my way here from your Goodreads review of Sacred Economics – and I wish there was a subscribe or like function as well!

Hey there. Thanks for your comment and for reading my work! I appreciate it. Will work on perhaps implementing a subscribe function. Thanks for the feedback!