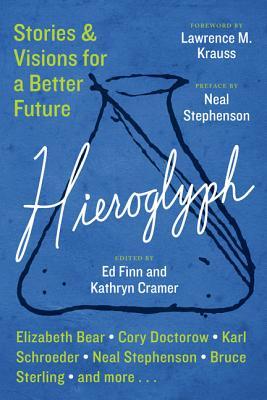

Book Review: Ed Finn and Kathryn Cramer’s “Hieroglyph”

by Miles Raymer

Hieroglyph: Stories & Visions for a Better Future is an outgrowth of Arizona State University’s Center for Science and the Imagination. Since the project was inspired by a Neal Stephenson essay (one of my favorite authors), I figured it would be an enlightening and worthwhile collection of speculative fiction. And while that turned out to be partly true, I was surprised to find myself resisting many of the assumptions on which these stories are founded. Not unlike many modern notions of progress, Hieroglyph suffers from split personality disorder. Taken as a whole, the book vacillates between humbly interconnected and shockingly egocentric visions for humanity’s near future. Such visions are not by definition mutually exclusive, but my sympathies and intellectual loyalties favor the former over the latter.

Editors Ed Finn and Cathryn Cramer claim that the tales in Hieroglyph are imaginative depictions of what they call the “moonshot idea”: “the intersection of a huge problem, a radical solution, and a breakthrough discovery that makes the solution possible now or in the near future” (xxv). It’s a promising idea, but one that can be easily mishandled. While a good chunk of Hieroglyph’s moonshot ideas would make worthy additions to any desirable human future, an equal portion offer little more than juvenile fantasies spun from myopic webs of profit-driven competition, socioeconomic inequality, and consolidated power.

Hieroglyph’s dark side stems from a mélange of ambitious whimsy and staggering disconnectedness from the mundane problems that ail normal human beings. The worst offenders here are Neal Stephenson, Geoffrey A. Landis, Gregory Benford, and Charlie Jane Anders. These authors write about small groups of people pursuing eccentric, large-scale tech dreams that vary in their practical usefulness and contain little or no moral substance: Building a 20-km tall tower in the middle of a desert, turning Antarctica into a tourist destination for the hyper-wealthy, pursuing interstellar travel by hoarding capital and tax dodging while global warming ravages an overpopulated Earth, and saving the planet by selling kitschy gadgets that secretly fight climate change to an idiotic, blindly-consumptive public. These might sound like fun pursuits for Silicon Valley tycoons and ambitious entrepreneurs, but most readers will disregard them as anti-social, haughty, and hubristic ideas that fail to seriously acknowledge––let alone significantly mitigate––the sufferings of normal folks and Earth’s compromised ecosystems.

The core problem here is a fundamental mistrust of average people and modes of collective self-governance. I’ll be the first to admit that modernity doesn’t always make a great case for cheering on the little guy or trusting democratically-elected governments. This would be a lot more damning, however, if corporations, autocracies, and the super-rich didn’t have equally awful––and oftentimes far more detestable––track records. Consider this moment from Benford’s “The Man Who Sold the Stars,” where protagonist Harold Mann learns he’s been indicted for massive tax fraud: “When he was growing up, the paradigm had been with liberty and justice for all, but now on a world stage jammed with swarming masses in desperate need, it seemed to be three hots and a cot and whatever you got” (342). Instead of facing the music, Mann decides to head into outer space with his wife, remarking, “‘This is going to be more fun than retirement to a prison'” (342). I’d be surprised if these same words hadn’t escaped the mouths of any number of white-collar criminals who caused the 2008 housing market meltdown. Benford should be ashamed to glorify such behaviors and the worldviews that justify them.

It would be disingenuous to claim that we don’t need ambitious individuals and wealthy companies to spur innovation and take big risks, but too often we ignore the greater context in which such pursuits take place. The aggregate results of small day-to-day actions taken by billions of normal people, combined with our still paltry understanding of the natural ecosystems on which all human communities depend, paints a confounding picture that is much harder to quantify or assess intuitively than the aspirations and soundbites of a highly visible socioeconomic elite. It’s easy to gawk at guys like Bill Gates and Elon Musk, shrug, and assume they will save civilization for us. It takes a lot more effort to imagine and actively pursue small, ameliorative progress within the scope of our personal lives and communities.

Although it gives voice to more than a few silly ideas and a handful of repugnant ones, this book is far from beyond redemption. Thanks to a group of feisty, empathic, and refreshingly creative authors, Hieroglyph also sheds light on ways in which future generations might better comprehend and improve ourselves and the natural world, giving birth to ethically responsible and physically sustainable communities. These authors indicate that such communities can be created via the cultivation of decentralized, technology-based methods of social organization that optimize collective action in order to solve big problems.

Hieroglyph’s best moments are summed up nicely by this assertion from Vandana Singh’s “Entanglement”: “The days of the lone ranger were gone; this was the age of the million heroes” (369). Singh and her fellow forward thinking authors (Kathleen Ann Goonan, Karl Schroeder, Brenda Cooper, and Elizabeth Bear) understand that technology’s greatest gift is its ability to circumvent physical and cultural boundaries by connecting individuals with overlapping interests and struggles in ways that enrich human experience while simultaneously generating workable solutions to our toughest challenges. Their stories make it clear that the various methods for accomplishing this are limited only by the human imagination. Here are some examples: Mentor-based education focused on learning through empathy; virtual reality overlays that impose ownership boundaries, capital flows, and civil disputes onto physical landscapes; social networking tools designed to clarify terms prior to community meetings and/or elections; wrist bands that monitor vital signs and moods in order to automatically match people up with friendly strangers in times of need; highly effective international activist networks enabled by enhanced texting, face-chats, and remotely controlled drones; advanced neuroscience techniques that transform psychopathic killers into beings capable of empathy and possible redemption.

My personal favorite of these is Karl Schroeder’s idea for an app called Wegetit:

There were two text fields, one for a word or concept (very short) and a longer one, for about a tweet’s worth of definition. You could let fly your idea of what something meant and wait. After a while, people would respond with restatements of your definition. If you thought a restatement accurately represented your meaning, you could click the Wegetit button. There was no button for disagreement…Somewhere out there were thousands of people who shared his understandings of many basic concepts, even if they might disagree with his politics. Wegetit was drawing lines connecting all those people, and every agreement strengthened the connections. (221)

Schroeder’s story suggests that collective use of such an app could radically improve the effectiveness of community and national decision-making by highlighting from the outset where different groups agree and disagree, obviating the need to clarify terms in the moment. This idea didn’t just make me smile and think––it filled me with effervescent excitement about the coming wave of apps that will pivot toward helping people do a lot more than buy consumer products or communicate frivolous personal details. It’s a great example of a truly worthy “moonshot idea,” one in which average people could easily participate. It also wouldn’t require a centralized authority or wealthy corporation to create and implement.

I’d rather this weren’t the case, but I can’t help but notice that almost all of Hieroglyph’s best stories (with one or two exceptions) were written by female authors, while all the ones that bothered me were written by men. This made me think that perhaps the futurist movement could use a solid injection of feminine brainpower. This could help move us away from male-dominated, radically individualist visions toward ones that are more democratic, distributed, and pluralistic. We need the next few decades to be “the age of the million heroes,” and while there are many ways to get there, there are also lots of ways to make societies even less equal, opportunities even scarcer, people even more blinded by competition rather than liberated by cooperation. We should take seriously the possibility that female leaders might be a key (or even the key) to nudging us in the right direction.

Hieroglyph closes with a charming and enigmatic story in which author Bruce Sterling lays down by far the wisest piece of prose in the Hieroglyph’s 500+ pages:

Mankind can build a Great Thing. Sometimes we do it. But then we have to live with the consequences of greatness. What does a Great Thing tell us about ourselves? Not that we are great, but that our Great Things are so rare, and so much abused. So many in our dreams, so few to loom like towers in the light of day. (506)

This trenchant passage just about cut me in half. The distance between our inflated notions of our own importance––both as individuals and as a species––and the reality of our “rare, and so much abused” Things of Greatness cannot be stressed enough. Still, few would dispute that we find ourselves at a critical juncture; the coming century will determine much about the long-term future of human civilization, and perhaps about the viability many other lifeforms on Earth. We lack the time and resources to waste any more of our Great Things, so we’d better do everything we can to make sure we pledge our loyalties to the best possible projects and minds. This mixed-bag of a book––every bit as capricious, inventive, self-obsessed, and noble as human nature itself––might help you sort out where your attentions and energies can be put to good use.

Rating: 7/10