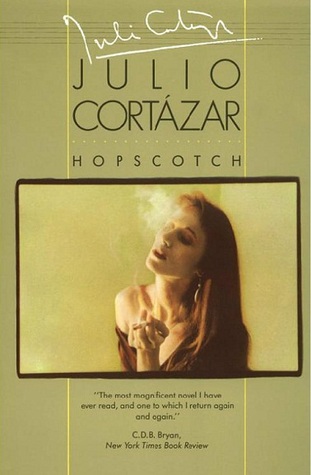

Book Review: Julio Cortázar’s “Hopscotch”

by Miles Raymer

In this novel’s table of instructions, Julio Cortázar states that Hopscotch “consists of many books, but two books above all.” The reader is given a choice: read the book in normal fashion and stop at the end of Chapter 56 (in which case a large portion of the book will remain unread), or jump between chapters in a prescribed order (this method includes all chapters). This choice is a false and rather insincere one, for only with great difficulty can I imagine a reader willing to stop midway through any book––excepting cases of extreme frustration or boredom––without wanting to experience the whole story. A dedicated enthusiast might undertake dual read-throughs to sample each method, but having finished using the hop-step approach, I’m in no rush to jump back into this enigmatic mess of a novel.

While Hopscotch contains some of the tropes we associate with traditional novels, it’s more concerned with subverting expectations than telling a story. As a fictionalized work of postmodern philosophy, its only firm conviction is that it has nothing concrete to say. Cortázar spills much ink obsessing over abstruse existential quandaries, failings of language, and the human preoccupation with our inability to access realms of pure essence/meaning.

This book’s downfall is its utter lack of characters with whom I can emotionally connect. Horacio Oliveira, the novel’s protagonist, is a self-serving, ultra-intellectual boob so mired in his own theoretical confusion that he fails at every turn to behave like a decent human being. I’m not typically hostile to antiheroes, but Oliveira is simply despicable in ways that preclude endearment. This is most evident in his consistently deplorable treatment of La Maga, his lover, and of women in general. Oliveira is a pompous posterboy for male chauvinism and all the worst aspects of machismo; he thinks women are incapable of participating in intellectual discourse and treats them as sex objects good for nothing more than making him tea and serving as vacuous receptacles for his sperm and/or philosophical pretensions (in whatever combination he happens to be spewing them). Throughout the novel, Oliveira surrounds himself with equally unlikable and even more uninteresting characters, all of whom––like Oliveira himself––fail to learn from their experiences or prove dynamic in any meaningful way.

Fans might claim that Hopscotch is not primarily concerned with characterization or progressive storylines, but rather with pushing the limits of literary form and posing questions about the nature of narrative consumption. Very well. I insist on an addendum, which is that the book, while structurally creative, is severely limited in its ability to illuminate much beyond the contradictory and destructive behaviors on which its endlessly circular conflicts are predicated.

Hopscotch would be quite horrendous if Cortázar were not such a tremendously gifted writer; his prose turns on a dime, cuts in an instant, and regularly embarks on fascinating and emotionally devastating flights of fancy. These moments are like powerful but rushed orgasms: they come on with great intensity but diminish quickly, leaving impressions more whimsical than profound. The quality of Cortázar’s thinking is top-notch, but, as with all postmodern philosophy, its contribution to the reader’s enlightenment is stymied by a bottomless lack of conviction.

Despite my harrumphing, it must be said that Hopscotch is without doubt a singular and brilliant piece of fiction that should probably be read by anyone with even a passing interest in literary theory. Such works are probably better appreciated by readers with a less specific sense of what they want from a novel. Cortázar’s potent message is lost on someone like me, who sees ingenious prose as a means to draw in an audience but not enough to deserve its full attention for 500+ pages. I need characters I can feel something about. I don’t need to like them or agree with them, but I need to care about what happens to them, to fret about where they will end up or how they will move forward.

From the outset, Hopscotch is so unwavering in its self-negation that it seems to end before it has even begun. It is a relic from a not-so-long-ago era when intellectualism was defined by the idea that meaningfulness itself might be among our most illusory and futile concepts. It is an excellent reminder of the many reasons why I feel fortunate to live in a world that has largely dispensed with such sophistry and moved on to better things.

Rating: 5/10

Thank you.

I read Hopscotch roughly 17 years ago. Certain moments of the narrative stay with me.

I did see him as sort of sympathetic character who became grotesque, but whom was still sort of sympathetic in his grotesqueness.

I read it at a time when I was affected by depression, and there was one passage in particular that resonated with me. He was describing the pull of depressive and cataclysmic emotions, comparing them to the way that a drain hole will pull water out of a sink. When we’re deeply depressed, we feel like we may ourselves get pulled down the drain. He said that, sure, maybe everyone feels this dreadful pull to some extent. But some of us feel the pull more than others. That resonated with me.

I personally feel like Oliveira was an adequate antihero. He was a misogynist. He practiced a sort of empty elitism, seeking escape in women, philosophy, cigarettes, booze, and zany adventures.

But there were moments when he realized that people were put at risk and sometimes got deeply hurt by his flippant attitude and behavior.

Philosophical nihilism is a monstrous thing on its own, but when it’s actually applied in life, it becomes an excuse for a destructive kind of hedonism that is neither noble nor heroic.

In the end I think that Hopscotch was an semi-effective warning against this kind of degeneracy.

We can seek joy, or at least solace, in the vampiric consumption of alcohol, entertainment, philosophy, and human souls. But these joys will be empty, and indeed they lead to further suffering.

Or we can dig deeper, and begin to excavate our own soul.

I think Hopscotch helped me see that cynical nihilism wasn’t where it’s at. It conveyed a sort of dysphoric absurdity. It didn’t really offer any solutions, which is kind of sickening. But it provoked me to find my own.

Hi Elliot!

Thanks very much for reading my review and leaving this thoughtful comment. You articulate your experience of the book with clarity and keen observation.

Your comment sent me to my notes, and I’m pretty sure I found the passage that stuck with you over the years:

“Between sleep and wakefulness, diving into washbasins. And it’s so easy, if you think about it a little, you ought to understand it. When you wake up, with the remains of a paradise half-seen in dreams hanging down over you like the hair on someone who’s been drowned: terrible nausea, anxiety, a feeling of the precarious, the false, especially the useless. You fall inward, while you brush your teeth you really are a diver into washbasins, it’s as if the white sink were absorbing you, as if you were slipping down through that hole that carries off tartar, mucus, rheum, dandruff, saliva, and you let yourself go in the hope that maybe you’ll return to the other thing, to what you were before you woke up, and it’s still floating around, is still inside you, is you yourself, but then it starts to go away…Yes, you fall inward for a moment, until the defenses of wakefulness, oh pretty words, oh language, take charge and stop you…In my case the washbasin really sucks me in.” (Chapter 57, 353-4).

I wonder if this will resonate with you today in the same way it did nearly two decades ago. It’s amazing and wonderful how such strings of words can work their way into our consciousness, memory, and identity.

Had I better understood your perspective when I read this years ago, I might have been able to conjure more sympathy for Oliveira and temper my haughty reaction to him. I agree with you that he’s an effective antihero––a symbol of how human life can be squandered instead of cherished. I hope you have learned to cherish yours in the way it deserves. 🙂

Take care and thanks again for taking the time to read and comment on my review!

This review put all the thoughts flying aimlessly in my head into concrete sentences. THANK YOU.

Hi Celeste! Thanks for reading and leaving this comment. Glad you enjoyed my review! 🙂

Hey Miles – Incisive review, sir! All valid points. I say this as a Julio fan. I even wrote a positive review of the novel (below). But,but, but…just tried to reread Hop. No can do. Julio’s imagination is much better suited to shorter work. —- https://glenncolerussell.blogspot.com/2023/08/hopscotch-by-julio-cortazar.html