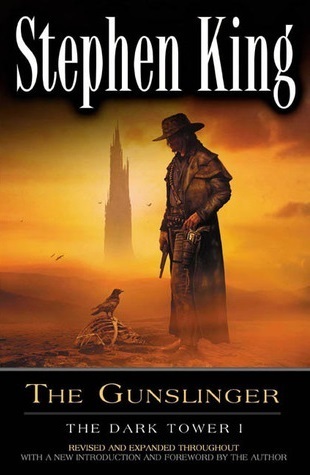

Book Review: Stephen King’s “The Gunslinger”

by Miles Raymer

I recently listened to a recording of Stephen King speaking and reading an excerpt from his latest book for a live audience, and was charmed by his rough candor and obvious affection for his doting readership. He seemed like a guy who’d be great to get a beer with (or seven). I’ve never done more than dip a toe into the vast King-sphere, so I thought this might be the right time to try out the first novel in his well-loved Dark Tower series. The Gunslinger has one of the best opening sentences I’ve ever read: “The man in black fled across the desert, and the gunslinger followed.” Sadly, the buzz from that delightfully simple and intriguing expository shot was spent quickly, not to be revived until the book’s final pages. The Gunslinger is a disjointed work that reads exactly like what it is: a group of loosely-related short stories unfairly styled as a coherent whole.

The gunslinger himself, like every character in this book, is more of an allegorical placeholder than a believable flesh-and-blood being. He is the classic western hero: gruff, moral according to his own personal code, and wholly fixated on achieving a bloody and probably impossible task. His austere mind was interesting for about 50 pages, at which point I began to realize that the gunslinger is a one-trick pony with little substance behind the facade of chiseled weariness and perfectly-weighted six-shooters. The boy with whom the gunslinger spends part of his journey is an equally hollow allegorical shell; I felt no emotion whatsoever when the gunslinger betrayed him despite professing a fatherly love that was neither well-developed nor believable for an honest second.

King’s sordid penchant for gratuitous sex and the inconsistent quality of his writing compound the problem of stilted characterization. I’m not opposed to graphic sexual descriptions as a rule, but they need to feel like more than pulpy placeholders disguising the fact that a writer hasn’t figured out how to help characters connect in less explicit, more nuanced ways. Nearly every single one of the women in this book is treated or referred to as a sexual object, and not in a fashion that serves genuine character or plot development. Additionally, King’s writing is sporadic in its quality; he is quite capable of spinning off terrific sentences and paragraphs, but too often falls back on one particular syntactic cadence that had me balking before I was halfway through the book:

They could see the smooth, stepped rise of the desert into foothills, the first naked slopes, the bedrock bursting through the skin of the earth in sullen, eroded triumph. Further up, the land gentled off briefly again, and for the first time in months or years the gunslinger could see real, living green. Grass, dwarf spruces, perhaps even willows, all fed by snow runoff from further up. Beyond that the rock took over again, rising in cyclopean, tumbled splendor all the way to the blinding snowcaps. Off to the left, a huge slash showed the way to the smaller, eroded sandstone cliffs and mesas and buttes on the far side. (126-7)

I realize that by many accounts this is a perfectly good piece of descriptive prose, but I couldn’t enjoy it because I became so fixated on King’s obnoxious tendency to rely repeatedly on the tedious “adjective, adjective” rhythm (“smooth, stepped,” “sullen, eroded,” “real, living,” “cycopean, tumbled” “smaller, eroded”). Just pick one damn adjective and stick with it! I wanted to shout. You already used “eroded” once in this paragraph––mix it up a bit! Such snooty critiques have been leveled at King all too often, so I guess I’m not doing a lot more than jumping on that already overburdened and pretentious bandwagon.

My nitpicking aside, the last chapter of this book is a real masterpiece of creative and metaphorical effort. The gunslinger finally catches up to the “man in black” (perhaps the novel’s most overwrought caricature), who unveils at least the rough draft of King’s Dark Tower concept. The idea is fascinating and in many ways just as vibrant in the context of the early 21st-century as it must have been in the 1980s. Without revealing too much, here’s a little taste:

If you fell outward to the limit of the universe, would you find a board fence and signs reading DEAD END? No. You might find something hard and rounded, as the chick must see the egg from inside. And if you should peck through that shell (or find a door), what great and torrential light might shine through your opening at the end of space? Might you look through and discover our entire universe is but part of one atom on a blade of grass? Might you be forced to think that by burning a twig you incinerate an eternity of eternities? That existence rises not to one infinite but to an infinity of them? (288-9)

This passage, along with many others in the book’s denouement, is not only wonderfully imaginative, but also well-written by any standard. It wasn’t nearly enough to send me wading through the next few thousand pages that lead to this series’ climatic ascension of the Dark Tower, but it definitely helped me understand why many readers––ones with sensibilities more aligned with King’s style and narrative preoccupations––choose to press on.

Rating: 4/10