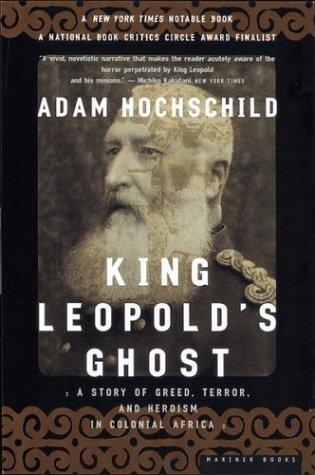

Review: Adam Hochschild’s “King Leopold’s Ghost”

by Miles Raymer

I am fortunate to have a mother who recommended this book and a father-in-law who gifted it to me. Given their convergent enthusiasm for this fascinating but grim piece of history, I expected something unique. Even so, I was unprepared for the wild ride of Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost.

This book is a quintessential example of the old saying that true life is stranger than fiction. Utilizing a combination of fluid prose and meticulous research, Hochschild’s narrative stretches the imagination and strains every moral fiber. It is the tale of King Leopold II of Belgium, an ambitious and deeply insecure monarch who, toward the end of the 19th century, made a brazen grab for a huge chunk of colonial Africa and––for a time––ruled over it with brutal and unchecked authority. Leopold’s exploitation of the Congo River Basin and its native peoples counts among the greatest atrocities in human history.

The book’s subtitle, “A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa,” is apt. These three words are indeed the best terms with which to explain Leopold’s atrocities and situate them in history while also re-contextualizing them using a modern lens. Greed is a vice that seeds the ambition of most rulers who seek an empire, and Leopold was no exception. As the second king in the newly-minted Belgian monarchy (the country gained independence in 1830), Leopold II felt inferior to the well-established European empires by which he was surrounded. Desperate to prove himself, Leopold’s sense of inferiority mingled dangerously with a ravening hunger for profit:

Leopold’s letters and memos, forever badgering someone about acquiring a colony, seem to be in the voice of a person starved for love as a child and now filled with an obsessive desire for an emotional substitute, the way someone becomes embroiled in an endless dispute with a brother or sister over an inheritance, or with a neighbor over a property boundary. The urge for more can become insatiable, and its apparent fulfillment seems only to exacerbate that early sense of deprivation and to stimulate the need to acquire still more. (38)

While it is not always best practice for a historian to psychologize his or her subject(s) of study, Hochschild’s thorough examination of Leopold’s life and behaviors leaves little doubt that he is correct, at least to some degree, in his assessment of the source and consequences of Leopold’s disposition.

Every villain needs a henchman, and Leopold found his in Henry Morton Stanley, a self-made adventurer who built an international reputation on a bewildering combination of tall tales and daring expeditions. Hochschild describes Stanley as “one part titan of rugged force and mountain-moving confidence; the other a vulnerable, illegitimate son of the working class, anxiously struggling for the approval of the powerful” (62). With Leopold manipulating the money and business relationships from afar, and Stanley cutting his way through the Congo Basin looking for new resources to extract and natives to enslave, it was a match made in hell.

Stanley and the wave of colonizers that followed him soon controlled huge swaths of the Congo, their physical presence a placeholder for Leopold’s remote but unquestioned authority. Ivory was their most lucrative export at first, but was surpassed by rubber starting in the 1890s. The reign of terror necessary to establish and sustain such an operation was swiftly institutionalized. The Force Publique––Leopold’s regional enforcers––press ganged natives into hard labor via a variety of brutal methods, including coercion through kidnapping, rape, torture, and outright murder. Profit was maximized at every turn, leading to the bleak environment that became the direct inspiration for Joseph Conrad‘s Heart of Darkness. Leopold’s opulent lifestyle kicked up a notch, fueled by the suffering of millions.

Hochschild’s research reveals a byzantine network of organizations, legal mechanisms, and financial pathways Leopold created to conceal and transfer his stolen wealth:

In setting up this structure, Leopold was like the manager of a venture capital syndicate today. He had essentially found a way to attract other people’s capital to his investment scheme while he retained half the proceeds. In the end, what with various taxes and fees the companies paid the state, it came to more than half. (117)

Perhaps the most insidious element of Leopold’s operation was how he depicted his presence in the Congo to Americans and other Europeans. Deploying rhetoric aligned with the “White Man’s Burden” ideology that characterized the turn of the century, Leopold assured the “civilized” world that he had only the best of intentions:

Ambitious as his and Stanley’s plans were, Leopold was intent that they be seen as nothing more than philanthropy. The contracts Stanley made his European staff sign forbade them to divulge anything about the real purpose of their work. “Only scientific explorations are intended,” Leopold assured a journalist. To anyone who questioned further, he could point to a clause in the committee’s charter that explicitly prohibited it from pursuing political ends. The king wanted to protect himself against the widespread feeling in Belgium that, for a small country, a colony would be a money-losing extravagance. He also wanted to do nothing to alert any potential rivals for this appetizing slice of the African cake. (65)

Leopold and his cronies claimed that humanitarian efforts were their primary aim, including scientific exploration, Christian charity, education, the abolition of slavery in the Congo (a thriving practice even before Stanley’s arrival), the creation of hospitals, and the general empowerment of the native population.

Of course, nothing could have been further from the truth. But how would the world discover this? This question can be answered by examining the powerful streak of heroism that runs through Hochschild’s story––the sole element that saves the book from being intolerably depressing. George Washington Williams, an African-American, was the first to speak out about what was really happening in the Congo. Viewing the Congo as a potential reception point for African-Americans who wanted to leave the United States and return to their continent of origin, Williams traveled to the Congo to investigate. Although prone to embellishing the facts of his personal origins and credentials, Williams appears to have been completely truthful about what he witnessed there: “Whatever Williams’s elaboration of his own résumé, virtually everything he wrote about the Congo would later be corroborated––abundantly––by others” (114).

There is a long list of brave individuals who followed in Williams’s footsteps; the two most notable are E.D. Morel and Roger Casement. Morel was a British citizen who undertook one of history’s most heroic investigative efforts:

His prodigious capacity for indignation seems to be something he was born with, as some people are born with great musical talent. After learning what he had in Brussels and Antwerp, he writes, “to have sat still…would have been temperamentally impossible.”

It was this smoldering sense of outrage that led Morel to become, in short order, the greatest British investigative journalist of his time. Once he determined to find out all he could about the workings of the Congo and to reveal it to the world, he produced a huge, albeit sometimes repetitive, body of work on the subject: three full books and portions of two others, hundreds of articles for almost all the major British newspapers, plus many written in French for papers in France and Belgium, hundreds of letters to the editor, and several dozen pamphlets. (187)

This is even more impressive given that Morel was completely unaided by the multimedia tools available to contemporary journalists. Morel’s activist outpourings were complemented by the perspective of Casement, who, unlike Morel, had traveled extensively in the Congo and had seen its horrors firsthand. Casement was a supporter of Irish independence as well as a homosexual, and was therefore able to empathize with the oppressed peoples of the Congo in ways few other white men could:

He was a man possessed. His anger at what he saw had a dramatic effect on many of the other Europeans he encountered; it was as if his visible outrage gave them permission to act on stifled feelings of their own. (201)

Morel and Casement were not just fellows in service of the same cause, but also became good friends. This observation––that the pursuit of compassion and moral duty can have global effects while simultaneously forging meaningful and lasting relationships between individuals––is one of the most important lessons a reader can take away from King Leopold’s Ghost. Together, Morel, Casement, and others who joined the movement generated a critical moment in the global development of human rights:

Among its supporters, it kept alive a tradition, a way of seeing the world, a human capacity for outrage at pain inflicted on another human being, no matter whether that pain is inflicted on someone of another color, in another country, at another end of the earth. (305)

Sadly, Leopold’s Ghost lingered long after the petulant monarch’s death. Hochschild demonstrates the tragic and long-lasting effects of the Congo’s colonization, showing how and why it remains one of the world’s most violent places. Not only did Leopold’s practices provide a blueprint for other European powers participating in the disgraceful Scramble for Africa, but the United States also got its hands dirty. Much of the rubber used to fight World War II was extracted from the Congo, as well as “more than 80 percent of the uranium in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs” (279). Worse still, the US government played an active role in the brutal murder of the Congo’s first democratically-elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, and supported the vicious dictator who replaced him.

The only obvious failing of this book is lamented by the author in the Afterword:

My greatest frustration lay in how hard it was to portray individual Africans as full-fledged actors in this story. Historians often face such difficulties, since the written record from colonizers, the rich, and the powerful is always more plentiful than it is from the colonized, the poor, and the powerless. Again and again it felt unfair to me that we know so much about the character and daily life of Leopold and so little about those of the Congolese indigenous rulers at the time, and even less about the lives of villagers who died. (313)

Despite the regrettable absence of voices drowned in the torrent of injustice, Hochschild has created something of deep value. King Leopold’s Ghost forces us to confront the darkest parts of human nature and culture, but also demonstrates the undeniable progress sprung from Enlightenment ideals. Leopold’s mistreatment of the Congo is and should remain a source of indignation and critique, and the actions of those who resisted reveal humanity’s commitment to the betterment of life for all peoples, which endures even in the face of tremendous hardship.

Rating: 8/10

Hey Miles,

Thanks for the fascinating overview. Immediately this exhibition that I saw in Berlin came to mind: https://www.dhm.de/en/ausstellungen/archive/2016/german-colonialism/the-exhibition.html

(pardon the fact that I don’t know how to insert a link)

Keep up the historical investigations!

Super cool. Thanks for sharing, Carissa!

Really good review! You mentioned: “…European powers participating in the disgraceful Scramble for Africa, but the United States also got its hands dirty.” I know it’s a little different issue than the partitioning debacle, but I think we already had our hands dirty from a little enterprise known as slavery as far as African disgraces go! just sayin’…

Haha, good point!