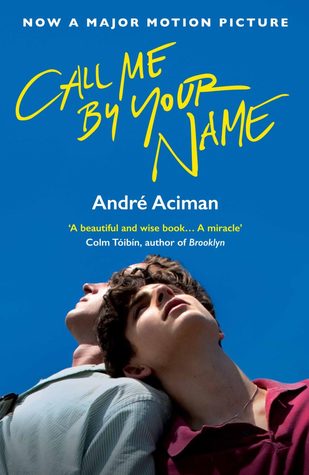

Review: André Aciman’s “Call Me by Your Name”

by Miles Raymer

André Aciman’s Call Me by Your Name is a tender love story that ultimately failed to seduce me. The protagonist is Elio, a precocious seventeen-year-old poised to blossom into a gifted musician. The bulk of the book takes place during the summer of 1987, when a beautiful twenty-four-year-old pre-Socratic scholar named Oliver comes to live with Elio and his family on the Italian coast. Elio becomes obsessed with Oliver, manages to eventually win him, and then spends the next couple decades battling with the feeling that no other intimate relationship may ever surpass the authenticity and emotional force of the fleeting weeks that he and Oliver spent together.

The best thing that Call Me by Your Name has going for it is Aciman’s prose, which is powerful and emotionally rich by any standard:

Did I want to be like him? Did I want to be him? Or did I just want to have him? Or are “being” and “having” thoroughly inaccurate verbs in the twisted skein of desire, where having someone’s body to touch and being that someone we’re longing to touch are one and the same, just opposite banks on a river that passes from us to them, back to us and over to them again in this perpetual circuit where the chambers of the heart, like the trapdoors of desire, and the wormholes of time, and the false-bottomed drawer we call identity share a beguiling logic according to which the shortest distance between real life and the life unlived, between who we are and what we want, is a twisted staircase designed with the impish cruelty of M.C. Escher. (67-8)

Aciman’s many tempting descriptions of male beauty complement his ruminations about the nature of desire:

To think that I had almost fallen for the skin of his hands, his chest, his feet that had never touched a rough surface in their existence––and his eyes, which, when their other, kinder gaze fell on you, came like the miracle of the Resurrection. You could never stare long enough but needed to keep staring to find out why you couldn’t. (9)

Also striking are Aciman’s thoughts about how memory and love can blur identity, a theme toward which he pivots in the third and fourth acts. Elio’s obsession with Oliver eventually grows into a more mature deliberation about the mysteries of memory and past relationships––how they shape our identities long after passion has died or gone dormant, and the feeling of helplessness that arises when we confront emotions and events which can be recalled in an instant but never truly relived:

It would finally dawn on us both that he was more me than I had ever been myself, because when he became me and I became him in bed so many years ago, he was and would forever remain, long after every forked road in life had done its work, my brother, my friend, my father, my son, my husband, my lover, myself. In the weeks we’d been thrown together that summer, our lives had scarcely touched, but we had crossed to the other bank, where time stops and heaven reaches down to earth and gives us that ration of what is from birth divinely ours. (243-4)

Despite these terrific passages and many more, I didn’t like this book very much. My critiques are all a matter of personal preference, and I don’t believe any of them impeach the overall quality of Aciman’s work, which is undeniably elegant and heartfelt.

I’ll begin with my pettiest complaint. When it came to connecting to this novel’s erotic center, my heterosexual imagination utterly failed me. I’m a little ashamed to admit this, but I always strive for unvarnished honesty in my reviews, so I’ll just state it plainly: I did not enjoy reading about explicit sex acts between two men. I didn’t feel neutral about it; I actively disliked it. This reaction tells me nothing about the nature of gay sex or about Aciman’s talents as a writer, but it does tell me a lot about the limitations of my own sexual openness.

My other two gripes are more substantial. First, Call Me by Your Name doesn’t offer much in the way of plot. It became difficult to endure Elio’s one-track inner monologue, which catalogs every detail of Oliver’s physique and comportment as he apricates in various states of almost-comical sumptuousness. Aciman offers an apt rendering of the ways in which first love inflames young passions, but after the first hundred pages or so, I began to realize that the story wasn’t really going to include much else. There are only a handful of supporting characters, and none of them is particularly well-developed (with the arguable exception of Elio’s endearing father). The book is sorely lacking in subplots that would allow the reader to momentarily escape Elio’s lovestruck consciousness, which eventually becomes predictable and tiresome.

Finally, I was annoyed by the feeling that there seemed to be very little at stake for any of the characters in Call Me by Your Name. Although Elio does experience some degree of apprehension regarding his homosexual urges, he is embedded in a family and social environment that appear to accept such predilections. His family is rich, educated, and they employ servants that do all the cooking, cleaning, and estate-care. Everything happens poolside, oceanside, or in picturesque cafes, bookstores, and discotheques nearby. The discussions between characters are overwhelmingly intellectual, and rarely rooted in any kind of intimacy with the world as most people experience it. This tranquil and luxurious environment made it difficult for me to feel invested in or excited about the relationship, despite the obvious sincerity of Elio and Oliver’s mutual affection.

Rating: 5/10