Review: Chris Arnade’s “Dignity”

by Miles Raymer

In winter 1993, journalist David Simon and ex-policeman Edward Burns began conducting what would become a full year of daily interviews on a drug corner on Fayette Street in West Baltimore. They became familiar with the residents, many of whom were heroin and cocaine addicts and drug dealers. Simon and Burns recorded their experiences and, in 1997, published them in a book called The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood. This book––one of the very best I have ever read––contains profound insights about the true nature of drug addiction and what life on the corner can teach us about America:

We want it [drug addition] to be about nothing more complicated than cash money and human greed, when at bottom, it’s about a reason to believe. We want to think that it’s chemical, that it’s all about the addictive mind, when instead it has become about validation, about lost souls assuring themselves that a daily relevance can be found at the fine point of a disposable needle…

This is an existential crisis rooted not only in race––which the corner has slowly transcended––but in the unresolved disaster of the American rust-belt, in the slow, seismic shift that is shutting down the assembly lines, devaluing physical labor, and undercutting the union pay scale. Down on the corner, some of the walking wounded used to make steel, but Sparrows Point isn’t hiring the way it once did. And some used to load container ships at Seagirt and Locust Point, but that port isn’t what she used to be either. Others worked at Koppers, American Standard, or Armco, but those plants are gone now. All of which means precious little to anyone thriving in the postindustrial age. For those of us riding the wave, the world spins on an axis of technological prowess in an orbit of ever-expanding information. In that world, the men and women of the corner are almost incomprehensibly useless and have been so for more than a decade now. (58-60)

More than two decades on, Chris Arnade’s Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America is proof that Simon and Burns’s plangent message fell on deaf ears. Though a very different kind of story––less exhaustive but broader in scope––Dignity is the first book to stir the same emotions in me as when I first read The Corner in 2009. This compassionate and heart-wrenching journey exposes in high definition America’s despicable treatment of its most vulnerable citizens, carrying on the honorable tradition of Simon, Burns, and many other writers and activists.

Arnade is a former Wall Street banker who quit his job in 2012 to start documenting drug addiction and poverty in the Hunts Point neighborhood of the Bronx. Over the next five years, he traveled across the United States, seeking out locations that “were poor and rarely considered or talked about beyond being a place of problems” (17). In these communities, he walked the streets and frequented churches and McDonald’s, talking to folks and taking pictures. The goal was to document “back row America,” which Arnade defines as people “fighting to maintain dignity” who have been “left behind, literally and figuratively” by an exclusive “front row” culture:

We wanted to get ahead––and we had. We were now in the front row of everything we did, not physically but hierarchically. We were at the top of our class, we went to the top colleges and top graduate schools, and we landed jobs in the top law firms, banks, universities, media companies, tech companies, and so on…We were mobile, having moved many times before, and we would move again. Staying put was seen as failure…We were well intended, but we had removed ourselves from the lived experiences of most of the country, including the places and people we wanted to help. The vast majority of minorities and the working poor were excluded from our club––by a lack of credentials and by a system rigged against them getting any…

If we were in the front row, they were the back row. They were the people who couldn’t or didn’t want to leave their town or their family to get an education at an elite college. The students who didn’t take to education, because it wasn’t necessarily their thing or because they had far too many obligations––family, friends, problems large and small––to focus on studying. They want to graduate from high school and get a stable job allowing them to raise a family, often in the same community they were born into.

Instead the back row is now left living in a banal world of hyper efficient fast-food franchises, strip malls, discount stores, and government buildings with flickering fluorescent lights and dreary-colored walls festooned with rules. They are left with a world where their sense of home and family and community won’t get them anywhere, won’t pay the bills. And with a world where their jobs are disappearing. (17, 44-7)

In Simon and Burns’s terms, front row Americans occupy “an axis of technological prowess in an orbit of ever-expanding information” while the back row becomes “almost incomprehensibly useless” to a society obsessed with economic productivity and material gain. This is somewhat reductive in that it ignores “middle row” Americans––those cut off from the first row but avoiding the back row through combinations of ingenuity, grit, privilege, and luck. I suspect there is also a healthy minority of potential front row occupants who pass on certain “opportunities” because they reject the front row’s worldview and lifestyle. Nevertheless, Arnade’s core framing mechanism provides a useful way of thinking and talking about socioeconomic inequality––a companion concept to Arlie Russell Hochschild‘s “waiting in line for the American Dream” image from Strangers in Their Own Land.

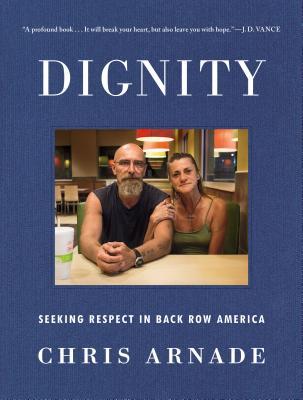

While Dignity doesn’t break a lot of new ground content-wise, it does have one quality that sets it apart from your typical work of nonfiction: physical presentation. The hardcover edition of Dignity is an absolute pleasure to handle and peruse. Most engaging are the color pictures Arnade took during his travels, which embrace the diverse experiences of his subjects. The pictures are broken into themed sections interspersed throughout the book and are also worked into the chapters, breathing a special life into Arnade’s prose. If you decide to read this, be sure to get a hard copy; an audiobook or ebook won’t do it justice.

Like his photography, Arnade’s writing is simple and direct. He does not romanticize or dramatize the back row with unnecessary flourishes. Each chapter focuses on a different aspect of back row life: the importance of McDonald’s as a “space where they could be themselves on their own terms” (38); how drugs “are a refuge” for people who produce “their own tight-knit communities” (81-2); religion’s function as a coping mechanism for those who “cannot ignore human fallibility” (119); why being told to pursue a better life by abandoning “the connections, networks, friends, family, congregations” of one’s hometown is insulting (152); racism’s historical role in creating a have and have-not geography that paves “the most dangerous” road to racial identity formation (212); and the risky, irrational acts taken by people who feel “humiliated” by their society’s “wholesale rejection that cuts to the core” (232-3). Arnade makes an effort to punctuate his narrative with reprieves of respect and perseverance, but it will surprise no one that Dignity is a grim, emotionally-draining read.

In critiquing the front row, Arnade uses himself as the main target. His expressions of humility are intelligent and genuine, as are his observations regarding the front row’s disconnectedness from the rest of the country:

We have implemented policies that focus narrowly on one value of meaning: the material. We emphasize GDP and efficiency, those things that we can measure, leaving behind the value of those that are harder to quantify––like community, happiness, friendships, pride, and integration. (283-4)

Separated by the ruthless definitions of our unjust economic system, Arnade concludes that front and back row Americans lack the ability to understand one another. Both sides bristle with a mutual intolerance that makes it increasingly difficult for us to solve collective problems, or even to agree on what our collective problems are. He’s not big on how-to-fix-it messages (it’s not that kind of book), but Arnade does take a cursory stab at what he thinks will help:

What are the solutions? What are the policies we should put in place? What can we do differently, beyond yell at one another? All I can say is “I don’t know” or the almost equally wishy-washy “We all need to listen to each other more.”

It is wishy-washy, but that is what I truly believe, because our nation’s problems and differences are just too big, too structural, and too deep to be solved by legislation and policy out of Washington. (282)

It’s true that Americans “all need to listen to each other more.” I say this without irony or cynicism, and concur with Arnade that any positive American future depends on citizens across the nation committing to open-minded discussion and productive compromise. However, I strongly disagree that “legislation and policy out of Washington” don’t have an equally or even more important role to play. It’s likely that sweeping government action is the only thing that can get us out of this mess. It won’t happen through new programs for abating addiction, or ending homelessness, or fixing racism, or job creation, or building better education or healthcare systems. Surely we must do all of those things, but we must first eradicate, once and for all, the existential crisis of abject poverty, which is upstream of all those problems and so many more. Ending poverty would not be a silver bullet, but it would remove our single largest barrier to socioeconomic and environmental progress. And guess what? We’re the richest country in human history. We have the money. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise.

Whether through a basic income, negative income tax, or some other form of massive wealth redistribution, America needs to dedicate more than warm words and sympathetic snapshots to aid our poorest citizens––to show each member of the back row that they’re one of us, and that a country in which everyone can flourish is preferable to one where some enjoy unchecked growth while others languish. For readers interested in digging into the numbers and arguments for abolishing poverty, I recommend Andrew Yang‘s The War on Normal People and Rutger Bregman‘s Utopia for Realists.

I can understand why Arnade doesn’t venture into this territory. Maybe he doesn’t agree with me and others who’d like to see our government fight a war on poverty, or perhaps he thinks he will reach a wider audience if he doesn’t politicize his work––probably true in these hyper-polarized times. But at a gut level, I find it perplexing that his experiences left him uninspired by (or at least ambivalent about) concrete pathways to back row revitalization. Even so, Dignity is an impactful piece of art, one that I hope will educate and motivate many of my fellow Americans.

Rating: 8/10