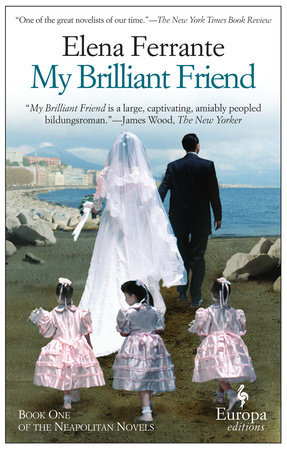

Review: Elena Ferrante’s “My Brilliant Friend”

by Miles Raymer

I often hear readers of contemporary literature speak of Elena Ferrante in hushed, reverential tones, so I’ve been curious for a while now to see what all the fuss is about. The brilliance of My Brilliant Friend was so subtle and supple that it almost escaped my notice, but in the end I came around, and can now situate myself firmly on the Ferrante bandwagon.

My Brilliant Friend is a story about Elena (our narrator) and Lila, two girls growing up together in postfascist Naples. It is the first in a four-book series called the Neapolitan Novels, with this installment covering Elena and Lila’s childhood and adolescent years. From the start, there were many barriers between my personal experience and those of these two young girls: gender, culture, socioeconomics, a generation (or two), geography. The story also has a large cast of characters with Italian names, so I was somewhat overwhelmed getting to know them all (although a handy Index of Characters is provided). My experience of the opening chapters felt similar to how Elena reacts to seeing the sea for the first time:

I had the impression that although I was absorbing much of that sight, many things, too many, were scattering around me without letting me grasp them. (loc. 1715)

Fortunately, these difficulties proved easy to overcome. The main reason for this was Ferrante’s superb writing, complemented by Ann Goldstein’s excellent translation from the original Italian. Like most great works of contemporary fiction, My Brilliant Friend displays a remarkable merger of simple language and complex emotional landscapes. Here are some samples:

It seemed to us that we were always going toward something terrible that had existed before us yet had always been waiting for us, just for us. When you haven’t been in the world long, it’s hard to comprehend what disasters are at the origin of a sense of disaster: maybe you don’t even feel the need to. Adults, waiting for tomorrow, move in a present behind which is yesterday or the day before yesterday or at most last week: they don’t want to think about the rest. Children don’t know the meaning of yesterday, of the day before yesterday, or even of tomorrow, everything is this, now: the street is this, the doorway is this, the stairs are this, this is Mamma, this is Papa, this is the day, this the night. (loc. 241)

There are no gestures, words, or sighs that do not contain the sum of all the crimes that human beings have committed and commit. (loc. 1935)

We are flying over a ball of fire. The part that has cooled floats on the lava. On that part we construct the buildings, the bridges, and the streets, and every so often the lava comes out of Vesuvius or causes an earthquake that destroys everything. There are microbes everywhere that make us sick and die. There are wars. There is a poverty that makes us all cruel. Every second something might happen that will cause you such suffering that you’ll never have enough tears. And what are you doing? A theology course in which you struggle to understand what the Holy Spirit is? Forget it, it was the Devil who invented the world, not the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. (loc. 3450)

As one might gather from those passages, there is a deep well of melancholy from which this novel draws inspiration. The main conduit for this melancholy is the fraught relationship between Elena and Lila, in which the admiration and affection the girls share for one another is constantly threatened by equally powerful feelings of envy and resentment. At its core, My Brilliant Friend is a treatise on the perils of a life lived by comparison, coupled with the despairing suggestion that there is perhaps no other sort of life humans are capable of leading. Elena’s journey toward young adulthood is bound up with her complex reactions to Lila’s development, which are as celebratory as they are covetous:

I didn’t know her well; we had never spoken to each other, although we were constantly competing, in class and outside it. But in a confused way I felt that if I ran away with the others I would leave with her something of mine that she would never give back…I did many things in my life without conviction; I always felt slightly detached from my own actions. Lila, on the other hand, had, from a young age…the characteristic of absolute determination. (loc. 302)

Although she was fragile in appearance, every prohibition lost substance in her presence. She knew how to go beyond the limit without ever truly suffering the consequences. In the end, people gave in, and were even, however unwillingly, compelled to praise her. (loc. 724)

I was blind, she a falcon; I had an opaque pupil, she narrowed her eyes, with darting glances that saw more; I clung to her arm, among the shadows, she guided me with a stern gaze. (loc. 3399)

I have never encountered a writer so capable of capturing in words the experience of deeply loving someone who makes you feel inferior and insignificant. Elena’s ability to blossom as an individual is directly related to her proximity to Lila. When Lila drops out of her life, Elena develops with ebullient splendor; when Lila inevitably reasserts herself, Elena questions her own worth and despairs of her ability to ever become Lila’s true equal.

This emotional roller coaster contains much suffering and more than a little self-pity. My Brilliant Friend would be in danger of falling prey to a kind of myopic narcissism if it didn’t also take up many of the universal human themes that reside at the heart of all great literature. Elena and Lila’s neighborhood in Naples is a microcosm in which all of human history plays itself out, crammed with cranky, petty people with endless appetites but few viable paths toward self-actualization. Ferrante invites the reader to consider how classism, poverty, tribalism, sexism, domestic abuse, postwar trauma, and mental illness keep humans locked in internecine conflicts, while also demonstrating how education, art, and acts of compassion can subvert and even resolve those conflicts under the right circumstances.

Although the horizon of this book’s ambitions is wide as the sky, its central focus never wavers. As Elena and Lila approach womanhood, Ferrante brings everything to a climax with artful poignancy; nowhere is this captured better than in Elena’s thoughts while gazing upon Lila’s naked body on her wedding day:

At the time it was just a tumultuous sensation of necessary awkwardness, a state in which you cannot avert your gaze or take away the hand without recognizing your own turmoil, without, by that retreat, declaring it, hence without coming into conflict with the undisturbed innocence of the one who is the cause of the turmoil, without expressing by that rejection the violent emotion that overwhelms you, so that it forces you to stay, to rest your gaze on the childish shoulders, on the breasts and stiffly cold nipples, on the narrow hips and the tense buttocks, on the black sex, on the long legs, on the tender knees, on the curved ankles, on the elegant feet; and to act as it it’s nothing, when instead everything is there, present, in the poor dim room, amid the worn furniture, on the uneven, water-stained floor, and your heart is agitated, your veins inflamed. (loc. 4173)

My Brilliant Friend represents a fearless confrontation of a painful and often unfaceable truth: Within each of us the ambitions of a million lives are born, and yet we only get one shot at this thing we call living. Ferrante stabs her pen straight into the heart of this problem, ripping from heartache a series of unforgettable questions: When we encounter an Other who epitomizes our own unrealized (and unrealizable) ambitions, is this a blessing or a curse? Can we overcome our feelings of inadequacy enough to appreciate the Other’s realization of these ambitions, or are we forever prisoner to the notion that these qualities must be our possessions or no one’s? And, most importantly, if this inimitable Other somehow sets its gaze on us and speaks the word “friend,” can we hear it?

Rating: 10/10