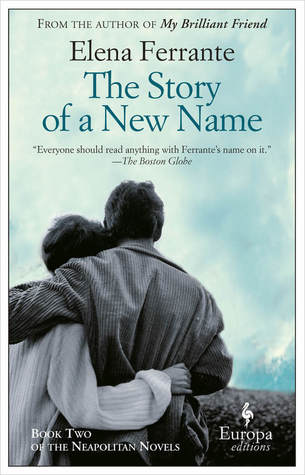

Review: Elena Ferrante’s “The Story of a New Name”

by Miles Raymer

Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels deserve every bit of the intense praise heaped on them by critics and readers. Even though I have only finished two of the four novels, it seems undeniable to me that this series occupies a superior position in 21st-century literature.

The second book picks up right where My Brilliant Friend left off, with all the urgency and emotional intensity that Ferrante packed into those final, brutal sentences. In The Story of a New Name, Ferrante thrusts Elena and Lila into young adulthood, sending new obstacles to challenge and hasten their development. The experience of reading these books is difficult to articulate, but a fitting description can be found inside its own pages:

The story is good, a contemporary story very well expressed, the writing is always surprising…On every page there is something powerful whose origin I can’t figure out. (452)

Ferrante’s use of language is like an imaginative blender in which the prosaic ingredients of human life coalesce into a delicious narrative smoothie. With unfailing consistency, she imbues a huge cast of Neapolitan subjects––fully decipherable only through the extremely useful index of characters provided at the front of the text––with mystery and tension. At the center of everything are Elena and Lila. As Elena grows into her role as our increasingly lovable and empathy-inducing narrator, Lila continues her legacy as the most furiously passionate and enigmatic best friend one could imagine.

As with the first novel, Ferrante forces the reader to confront the difficult intersection of class and gender roles. In these youthful years, Elena and Lila come to represent two ways of escaping (and yet not escaping) the confines of poverty: Elena studies hard to win herself a coveted place in higher education, and Lila marries a wealthy man. Lila’s marriage to Stefano, which Elena recognizes as “already over” before the sun sets on its first day, is dominated by a power struggle in which money and sex are used as leverage points and weapons (20). Stefano explains:

Lina, we just have to get a few things straight. Your name is no longer Cerullo. You are Signora Carracci and you must do as I say. I know, you’re not practical, you don’t know what business is, you think I find money lying on the ground. But it’s not like that. I have to make money every day, I have to put it where it can grow…If we don’t make money we don’t have this car, I can’t buy you that dress, we lose the house with everything in it, in the end you can’t act the lady, and our children will grow up like the children of beggars. So just try saying again what you said tonight and I will ruin that beautiful face of yours so that you can’t go out of the house. You understand? (34)

Stefano, trapped by his own gender role as male provider, would be sympathetic were it not for the cruel outbursts of violence portended in this passage. Lila, fierce as ever, finds all manner of ways to strike back at Stefano for his brutish comportment. Among her many wifely subversions is profligate spending:

What impressed me most, though, was her casual behavior with money. She went to the cash register and took what she wanted. Money for her was that drawer, the treasure chest of childhood that opened and offered its wealth. In the (rare) case that the money in the drawer wasn’t enough, she had only to glance at Stefano. (109-10)

Elena, for her part, trudges through the remainder of her secondary education before finally earning a place for herself at a university in Pisa. Though she is clearly a gifted student, Elena struggles with constant feelings of inferiority, always anxious that she is striving to enter a world in which she will never truly belong. This situation is complicated by her keen understanding that the most effective way to increase her acceptability in educated society is to show up on the arm of the right man:

I had quickly understood that Franco, his presence in my life, had masked my true condition but hadn’t changed it, I hadn’t really succeeded in fitting in. I was one of those who labored day and night, got excellent results, were even treated with congeniality and respect, but would never carry off with the proper manner the high level of those studies. I would always be afraid: afraid of saying the wrong thing, of using an exaggerated tone, of dressing unsuitably, of revealing petty feelings, of not having interesting thoughts. (404-5)

The inescapable fear that accompanies nascent maturity is probably the single most prevalent emotion expressed in this novel––one that Ferrante wields with stunning precision. This horror derives from the daily difficulties and indignities these young women must endure, combined with oceanic undertones that make the act of living feel exhausting and sometimes meaningless:

And then there was the lazy sea, the leaden sun that bore down on the gulf and the city, stray fantasies, desires, the ever-present wish to undo the order of the lines––and, with it, every order that required an effort, a wait for fulfillment yet to come––and yield, instead, to what was within reach, immediately gained, the crude life of the creatures of the sky, the earth, and the sea. (104)

I made the dark descent. Now the moon was visible amid scattered pale-edged clouds; the evening was very fragrant, and you could hear the hypnotic rhythm of the waves. On the beach I took off my shoes, the sand was cold, a gray-blue light extended as far as the sea and then spread over its tremulous expanse. I thought: yes, Lila is right, the beauty of things is a trick, the sky is the throne of fear; I’m alive, now, here, ten steps from the water, and it is not at all beautiful, it’s terrifying; along with this beach, the sea, the swarm of animal forms, I am part of the universal terror; at this moment I’m the infinitesimal particle through which the fear of every thing becomes conscious of itself. (289)

Elena and Lila, despite their compelling and unique talents, are too intelligent to overlook the shackles of history, tradition and nature that narrow their horizons of possibility. Watching them battle these restraints––sometimes in unity and sometimes in opposition––is both heartbreaking and deeply pleasurable.

As ever, their relationship is dominated by an obsession with perceived asymmetry––the gutting suspicion that one of them is truly prodigious while the other is a simpleton masquerading as worthy of attention and friendship. The dangers of comparison threaten even the strongest bonds, and the central satisfaction of The Story of a New Name is found in observing how Elena learns to articulate and (at least partially) overcome this dynamic:

Yes, it’s Lila who makes writing difficult. My life forces me to imagine what hers would have been if what happened to me had happened to her, what use she would have made of my luck. And her life continuously appears in mine, in the words that I’ve uttered, in which there’s often an echo of hers, in a particular gesture that is an adaptation of a gesture from hers, in my less which is such because of her more, in my more which is the yielding to the force of her less. (337, emphasis hers)

I understood that I had arrived there full of pride and realized that––in good faith, certainly, with affection––I had made the whole journey mainly to show her what she had lost and what I had won. But she had known from the moment I appeared, and now, risking tensions with her workmates, and fines, she was explaining to me that I had won nothing, that in the world there is nothing to win, that her life was full of varied and foolish adventures as much as mine, and that time simply slipped away without any meaning, and it was good just to see each other every so often to hear the mad sound of the brain of one echo in the mad sound of the brain of the other. (466)

Though nothing can surpass friendship in this regard, books are also a vehicle for transmitting the “mad sound of the brain” from one consciousness to another. I celebrate Ferrante’s adroitness at the narrative wheel, and am relieved that it is not yet time to bid farewell to Elena, Lila, and the solar system of Neapolitans in their orbit; to do so at this point would be devastating.

Rating: 10/10

Excellent review!

Thanks for reading! 🙂