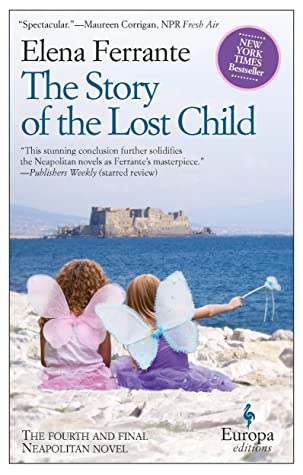

Review: Elena Ferrante’s “The Story of the Lost Child”

by Miles Raymer

There can be no doubt that Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels comprise one of the great literary masterpieces of the early 21st century. Even so, the end of this series left me numb, enervated to the point of apathy. It’s hard to tell if my reaction is the aberrant result of a desolate narrative’s collision with the very real tragedy of COVID-19, or if it was always bound to be this way. Whatever the case, I’m caught between my admiration for Ferrante’s accomplishment and the flatness of my emotional response to its conclusion.

For more than 1500 pages over four summers, I entered the mind of Elena Greco, a fictional Neapolitan writer whose life is destined to merge with that of her best friend, Lila. The Story of the Lost Child explores their friendship over the distance of decades as they enter maturity and old age. These women are irreplaceable companions but also nemeses, thrown together by fate and kept together by a mercurial but ineradicable thread of deep connection. This relationship is so complex that it feels impossible to satisfactorily summarize.

Many other themes fill out The Story of the Lost Child, some of them holdovers from previous books and some new. Ferrante’s meta-commentary on the practice of writing is especially sharp. “In my job,” Elena declares at one point, “I have to paste one fact to another with words, and in the end everything has to seem coherent even if it’s not” (262). Ferrante delights in creating critical loops through which she can celebrate and condemn an activity where “words rarely go to the right place, and if they do, it’s only for a very brief time” (78). These musings become mingled with Lila’s professional success as a computer programmer in the incipient digital revolution. Here’s how Elena describes her first encounter with word processing:

We locked ourselves in her office and sat at the computer, a kind of television with a keyboard, very different from what she had showed me and the children some time before. She pressed the power button, she slid dark rectangles into gray blocks. I waited, bewildered. On the screen luminous tremors appeared. Lila began to type on the keyboard, I was speechless. It was in no way comparable to a typewriter, even an electric one. With her fingertips she caressed gray keys, and the writing appeared silently on the screen, green like newly sprouted grass. What was in her head, attached to who knows what cortex of the brain, seemed to pour out miraculously and fix itself on the void of the screen. It was power that, although passing for act, remained power, an electrochemical stimulus that was instantly transformed into light. It seemed to me like the writing of God as it must have been on Sinai at the time of the Commandments, impalpable and tremendous, but with a concrete effect of purity. Magnificent, I said. I’ll teach you, she said. (311)

Though I remember the early days of boxy desktops, floppy disks, and dial-up Internet, I was too young to recognize computing in this way. For me, it was cool. For Ferrante’s generation, it was a miracle.

Ferrante also reveals the full character of Lila’s mental health struggles, which are hinted at but not fully explored in earlier volumes. In one incredible passage depicting the Irpina Earthquake of 1980, we discover just how tenuous Lila’s cognition has been all along:

She used that term: dissolving boundaries. It was on that occasion that she resorted to it for the first time; she struggled to elucidate the meaning, she wanted me to understand what the dissolution of boundaries meant and how much it frightened her. She was still holding my hand tight, breathing hard. She said that the outlines of things and people were delicate, that they broke like cotton thread. She whispered that for her it had always been that way, an object lost its edges and poured into another, into a solution of heterogeneous materials, a merging and mixing. She exclaimed that she had always had to struggle to believe that life had firm boundaries, for she had known since she was a child that it was not like that––it was absolutely not like that––and so she couldn’t trust in their resistance to being banged and bumped. Contrary to what she had been doing, she began to utter a profusion of overexcited sentences, sometimes kneading in the vocabulary of the dialect, sometimes drawing on the vast reading she had done as a girl. She muttered that she mustn’t ever be distracted: if she became distracted real things, which, with their violent, painful contortions, terrified her, would gain the upper hand over the unreal ones, which, with their physical and moral solidity, pacified her; she would be plunged into a sticky, jumbled reality and would never again be able to give sensations clear outlines. A tactile emotion would melt into a visual one, a visual one would melt into an olfactory one, ah, what is the real world, Lenù, nothing, nothing, nothing about which one can say conclusively: it’s like that. (175-6, emphasis hers)

Lila’s experience, which might be characterized as a kind of derealization disorder, is conceptually beautiful when confined to words but terrifying to contemplate as one’s perpetual reality.

The tension between professional ambitions and parental obligations creates a powerful conflict in Elena’s life. Whether it’s her disastrous romantic exploits or her successful-but-demanding writing career, she is always abandoning her children while still trying to find ways to nurture and love them:

What was bad for my children, what was their good? And bad for me, and my good, what did those consist of, and did they correspond to or diverge from what was bad and good for the children? (79)

I regretted not having been with the child, of having deprived her of my presence just when she needed me. Because now I didn’t know anything about how much and in what way she had suffered…Even now that I knew about my daughter’s illness, I couldn’t get rid of the satisfaction for what I had become, the pleasure of feeling free, moving all over Italy, the pleasure of disposing of myself as if I had no past and everything were starting now. (293)

Readers with children are likely to relate, and childfree readers will breathe a sigh of relief about their choice to abstain from parenthood. This all takes place in tandem with the decline and death of Elena’s mother, with generational affections and resentments running high.

Ferrante’s preoccupation with apocalyptic imagery emerges again in this novel, this time describing not only the historical natural disaster mentioned above, but also the failings of Western Civilization in general:

It became simpler to reflect on Naples, to write about it and let myself write about it with lucidity. I loved my city, but I uprooted from myself any dutiful defense of it. I was convinced, rather, that the anguish in which that love sooner or later ended was a lens through which to look at the entire West. Naples was the great European metropolis where faith in technology, in science, in economic development, in the kindness of nature, in history that leads of necessity to improvement, in democracy, was revealed, most clearly and far in advance, to be completely without foundation. To be born in that city––I went so far as to write once, thinking not of myself but of Lila’s pessimism––is useful for only one thing: to have always known, almost instinctively, what today, with endless fine distinctions, everyone is beginning to claim: that the dream of unlimited progress is in reality a nightmare of savagery and death. (337)

This passage, though stunning in structure, purveys an incomplete and reductive interpretation of progress as it arises in this or any human era. It smacks of postmodern superiority––the worst kind of elitism that almost always comes from someone for whom modernity has worked out quite well. Perhaps Ferrante is being ironic, perhaps not, but this perspective was one of the things that prevented my total emotional investment in this novel. Fortunately, the true nature of progress––inconstant and fragile but undeniable––is vigorously honored by the Neapolitan Novels as a whole.

True to itself, every word of The Story of the Lost Child hinges on the always-mutating bond between Elena and Lila:

The very nature of our relationship dictates that I can reach her only by passing through myself…Now that I’m close to the most painful part of our story, I want to seek on the page a balance between her and me that in life I couldn’t find even between myself and me. (25)

What a waste it would be, I said to myself, to ruin our story by leaving too much space for ill feelings: ill feelings are inevitable, but the essential thing is to keep them in check. (138-9)

At that moment I felt happy, satisfied with myself, and so I also felt, very clearly, that I loved my friend for how she was, for her virtues and her flaws, for everything. (264)

Every intense relationship between human beings is full of traps, and if you want it to endure you have to learn to avoid them. (451)

It’s only and always the two of us who are involved: she who wants me to give what her nature and circumstances kept her from giving, I who can’t give what she demands; she who gets angry at my inadequacy and out of spite wants to reduce me to nothing, as she has done with herself, I who have written for months and months and months to give her a form whose boundaries won’t dissolve, and defeat her, and calm her, and so in turn calm myself. (466)

There’s no easy way out here, no redemptive moment or restorative event to banish antipathy and secure love in perpetuity. All we have is the unpredictable, often-cruel and sometimes-merciful pulses of real life, which, “Unlike stories…inclines toward obscurity, not clarity” (473).

Rating: 9/10