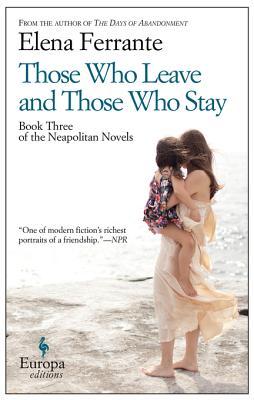

Review: Elena Ferrante’s “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay”

by Miles Raymer

For three summers running, I have welcomed one of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels into my life. Each has helped me rediscover the beautiful and complex ways in which emotional experience becomes simultaneously trapped and liberated by the act of articulation. Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, the penultimate installment in this narrative quartet, breaks new ground while proving every bit as brilliant as its two predecessors.

This novel covers “Middle Time”––the period when our narrator Elena, her best friend Lila, and the host of Neapolitans from their childhood community take on the risks, responsibilities, and revelations that come along with maturation. In her incisive and inimitable fashion, Ferrante continues to interrogate the central themes that drive the series: the ambiguities of friendship, the suffocating intricacies of gender roles, and the tension between capitalism and labor. Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay adds some additional concerns to this already-weighty list, including the nature of madness, the challenges of motherhood, the advent of the digital age, and the question of whether personal reinvention is possible as we age.

The book’s title admits at least three interpretations: First, this stage of Elena and Lila’s lives is clearly about the consequences of either leaving or staying in Naples itself. Second, these years tell the story of how they choose to remain in or abandon their most profound romantic ties. Third, all adults must grow out of their younger selves to some extent, but it is always an open question how much of their childhood will leave them in peace or stay behind as some combination of comforter and torturer.

Amidst the throes of adulthood, Elena and Lila’s friendship continues to mutate. As each woman pursues a different version of success in a male-dominated culture and economy, each learns the extent to which childhood bonds can be strengthened, transformed, or broken. As always, events seem smeared across a landscape of tragedy––one in which any choice to leave or stay may ultimately prove meaningless:

Leave, instead. Get away for good, far from the life we’ve lived since birth. Settle in well-organized lands where everything really is possible. I had fled, in fact. Only to discover, in the decades to come, that I had been wrong, that it was a chain with larger and larger links: the neighborhood was connected to the city, the city to Italy, Italy to Europe, Europe to the whole planet. And this is how I see it today: it’s not the neighborhood that’s sick, it’s not Naples, it’s the entire earth, it’s the universe, or universes. (28)

The new living flesh was replicating the old in a game, we were a chain of shadows who had always been on the stage with the same burden of love, hatred, desire, and violence. (291)

Cynical though Elena can be, her profound desire to understand herself and her world is more inspiring than ever. Now a wife and mother, we see Elena battling with her past in a desperate and heroic struggle for self-determination, bouncing chaotically between states of passionate longing and staid acceptance:

Become. It was a verb that had always obsessed me, but I realized it for the first time only in that situation. I wanted to become, even though I had never known what. And I had become, that was certain, but without an object, without a real passion, without a determined ambition. I had wanted to become something––here was the point––only because I was afraid that Lila would become someone and I would stay behind. My becoming was a becoming in her wake. I had to start again to become, but for myself, as an adult, outside of her. (346-7, emphasis hers)

I said to myself that maturity consisted in accepting the turn that existence had taken without getting too upset, following a path between daily practices and theoretical achievements, learning to see oneself, know oneself, in expectation of great changes. Day by day I grew calmer. (353)

Ever since I was a child I had constructed for myself a perfect self-repressive mechanism. Not one of my true desires had ever prevailed. I had always found a way of channeling every yearning. Now enough, I said to myself, let it all explode, me first of all. (398-9)

These passages convey the intense dynamism of Elena’s character development, which accelerates thrillingly as the novel reaches its denouement. Again Ferrante leaves us on the precipice of a portentous moment, but this time brimming with a new joy that could either elevate Elena to an entirely new realm of self-discovery, or bring about a heretofore unimaginable plunge into suffering.

Rating: 10/10