Review: Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt’s “The Coddling of the American Mind”

by Miles Raymer

The Coddling of the American Mind is a book that every American should read. While this was my first encounter with author Greg Lukianoff, I’ve long respected and followed the work of his coauthor, Jonathan Haidt. In the early 2010s, Haidt’s The Righteous Mind was one of my gateway texts into the field of moral psychology, which has captivated me ever since.

In this new book, Lukianoff and Haidt team up to take on a host of controversial issues, including freedom of expression, outrage on college campuses, and the general culture of “safetyism” that is on the rise in modern America:

“Safetyism” refers to a culture or belief system in which safety has become a sacred value, which means that people become unwilling to make trade-offs demanded by other practical and moral concerns. “Safety” trumps everything else, no matter how unlikely or trivial the potential danger. (30)

The Coddling presents a fine-grained examination of safetyism, which is driven by an insidious form of concept creep that equates emotional/psychological safety with physical safety. The authors combine a battery of empirical research with clear, concise arguments that demonstrate the downsides of conflating these two concepts, and outline a number of positive methods for identifying and avoiding this cognitive distortion in everyday life.

Before highlighting what I found to be the most important aspects of Lukianoff and Haidt’s findings, a few words of criticism regarding this book’s title and cover. I usually don’t comment on such trivial matters, but in this case I feel compelled to make an exception. I think The Coddling of the American Mind is a needlessly abrasive title that will likely put off potential readers before they have the chance to give the book’s content a fair hearing. Combined with a harsh red cover depicting nondescript young people in graduation caps falling off a cliff like lemmings, I’m afraid this book will be written off by many of the people who would benefit most from reading it. I hope this fear is unjustified, and certainly don’t blame the authors for the unfortunate decisions of their publisher.

Contrary to what the title and cover might imply, this is not an anti-left screed or a histrionic lament about how “snowflakes” are ruining American society. Lukianoff and Haidt’s tone is consistently civil and charitable to the opposition, as evidenced by this representative passage:

This is a book about good intentions gone awry. In…the book, you’ll read about people primarily acting from good or noble motivations. In most cases, the motive is to help or protect children or people seen as vulnerable or victimized. Our goal…is not to blame; it is to understand. (126)

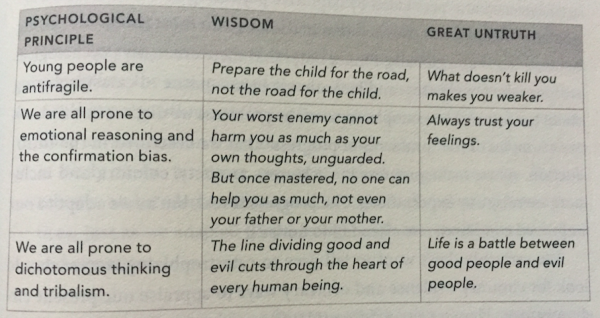

In their attempt to understand what’s going on when good intentions lead to negative results, Lukianoff and Haidt posit three “Great Untruths” that they claim are enfeebling American society:

- The Untruth of Fragility: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

- The Untruth of Emotional Reasoning: Always trust your feelings.

- The Untruth of Us Versus Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people. (4)

These Great Untruths run contrary to ancient wisdom as well as modern psychological research, and also harm the individuals and communities who embrace them (4). Lukianoff and Haidt pair each Untruth with a proposed psychological antidote, as shown here:

One key to understanding why the Great Untruths can be so harmful lies in Nassim Taleb‘s concept of “antifragility”:

Many of the important systems in our economic and political life are like immune systems: they require stressors and challenges in order to learn, adapt, and grow. Systems that are antifragile become rigid, weak, and inefficient when nothing challenges them or pushes them to respond vigorously. (23, emphasis theirs)

When we seek to protect people from all possible dangers, we deny them the chance to exercise the inherent growth mechanisms that build up their antifragility and transform them into more robust, resilient citizens. Without strain and strife, people languish.

Using myriad examples, Lukianoff and Haidt demonstrate how the Great Untruths can produce all manner of undesirable outcomes: unnecessary social acrimony; neurotic parenting; a fanatic adherence to safetyism; depression and anxiety; and even physical violence against innocent victims as a means of “protecting” vulnerable individuals and groups. These sections focus primarily on parents and young people, but will be engaging and useful for any curious reader seeking to shore up his or her own antifragility.

Lukianoff and Haidt also have much to say about the touchy topic of identity politics. They distinguish between two types of identity politics: common-humanity and common-enemy. Common-humanity identity politics focuses on widening the reach of societal compassion with the goal of promoting equal rights and access to opportunity for all people, regardless of race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, etc. This approach, which was championed by Martin Luther King, Jr. and many other civil rights activists, seeks to overcome political division by positing our shared humanity as the most important (but certainly not the only important) driver of political and social progress:

The more you separate people and point out differences among them, the more divided and less trusting they will become. The more you emphasize common goals or interests, shared fate, and common humanity, the more they will see one another as fellow human beings, treat one another well, and come to appreciate one another’s contributions to the community. Pauli Murray expressed the power of this principle when she wrote, “When my brothers try to draw a circle to exclude me, I shall draw a larger circle to include them.” (260)

Common-humanity identity politics stands in stark contrast to common-enemy identity politics, whose practitioners succumb to the Great Untruth of Us Versus Them. This phenomenon is as old as humanity itself, and capitalizes on our native tribal instincts that crave an unambiguous distinction between in-groups (good people) and out-groups (bad people). Lukianoff and Haidt show how the practice of common-enemy identity politics on both ends of the political spectrum leads to a “call-out culture” in which intelligent political discourse degrades rapidly and heterodox views are suppressed. Other negative results include dehumanizing one’s political opponents, participation in violent protests, and cycles of mutual provocation that chip away at the political center and leave little room for nuanced and fact-based debate.

Lukianoff and Haidt’s firm rejection of common-enemy identity politics and support for common-humanity identity politics is a great example of their readiness to compromise with those who might disagree with them. Given the recent idiocies that have been enabled by common-enemy identity politics on both the left and right, it’s becoming increasingly easy for pundits to reject identity politics outright, claiming that differences in identity should play no role at all in political life. Even if this is correct in some theoretical or idealistic sense, this approach comes off as ahistorical and dismissive of the perfectly legitimate grievances of minority communities and marginalized groups. Common-humanity identity politics provides a platform on which we can celebrate difference while simultaneously forming coalitions based on our common biological inheritance. Modern science has taught us that biological similarities trump cultural differences more often than not, and it’s time to bring that reality to the forefront of our political movements:

As a result of our long evolution for tribal competition, the human mind readily does dichotomous, us-versus-them thinking. If we want to create welcoming, inclusive communities, we should be doing everything we can to turn down the tribalism and turn up the sense of common humanity. (70)

The role of American universities in fanning the flames of political division is another hotly-contested subject that Lukianoff and Haidt tackle. The politicization of higher education is nothing new, but the most visible forms of protest that have exploded on campuses in recent years have taken on a new and particularly irrational flavor. The Coddling contains lots of good advice about how university students, professors and administrators can help one another take a deep breath and stymie unnecessary outrage and violence. Most importantly, Lukianoff and Haidt remind us that the main charge of a university is to seek out and disseminate truth, not to be a vehicle for social change:

Some students and faculty today seem to think that the purpose of scholarship is to bring about social change, and the purpose of education is to train students to more effectively bring about such change.

We disagree. The truth is powerful, yet the process by which we arrive at truth is easily corrupted by the desires of the seekers and the social dynamics of the community. If a university is united around a telos of change or social progress, scholars will be motivated to reach conclusions that are consistent with that vision, and the community will impose social costs on those who reach different conclusions––or who merely ask the wrong questions. (254)

Should universities abandon their allegiance to truth in favor of an ethos of social change, a great and powerful tool for enlightenment will become corrupted, perhaps irredeemably. People who denigrate the idea of truth and seek an activist agenda for universities, even with the best of intentions, are forgetting the fact that social change will happen no matter what––it always does. The proper role of a university is to inoculate the process of social change with facts and reason, not to direct the process itself or predetermine its outcome. Above all else, education should be about creating good thinkers:

It is challenging to think well; we are easily led astray by feelings and by group loyalties. In the age of social media, cyber trolls, and fake news, it is a national and global crisis that people so readily follow their feelings to embrace outlandish stories about their enemies. A community in which members hold one another accountable for using evidence to substantiate their assertions is a community that can, collectively, pursue truth in the age of outrage. Emphasize the importance of critical thinking, and then give students the tools to engage in better critical thinking. (259)

At its heart, The Coddling calls us back to a simple practice that, while it has always had positive utility, is now becoming a critical feature that will differentiate healthy 21st-century societies from lost or doomed ones. This is the practice of giving people the benefit of the doubt, of assuming the best of intentions (or at least neutral intentions) unless one has very good reason not to:

It is important to find out whether an acquaintance feels hostility or contempt toward you. But it is not a good idea to start by assuming the worst about people and reading their actions as uncharitably as possible. This is the distortion known as mind reading; if done habitually and negatively, it is likely to lead to despair, anxiety, and a network of damaged relationships. (40-1, emphasis theirs)

One of the pitfalls of the information age is that we suddenly think we’re so damned smart, that we can understand other people better than they understand themselves. We read books and articles that purport to teach us how to detect “unconscious bias,” and gobble up partisan podcasts that so keenly articulate the assumed stances of our political and cultural opponents that we don’t feel the need to actually engage with them. I am just as guilty of this as most people, but I’m trying hard to break the habit, as should all Americans.

We can start with an enthusiastic revival of the principle of charity, and with following Lukianoff and Haidt’s rules for productive disagreement:

- Frame it as a debate, rather than a conflict.

- Argue as if you’re right, but listen as if you’re wrong (and be willing to change your mind).

- Make the most respectful interpretation of the other person’s perspective.

- Acknowledge where you agree with your critics and what you’ve learned from them. (240)

Lukianoff and Haidt have offered up a terrific text that carries on the long American tradition of cultural critique; they clearly love America and want it to live up to its promise. Probably the best quote in the whole book is lifted from an interview with Van Jones, one of my political heroes:

I don’t want you to be safe ideologically. I don’t want you to be safe emotionally. I want you to be strong. That’s different. I’m not going to pave the jungle for you. Put on some boots, and learn how to deal with adversity. I’m not going to take all the weights out of the gym; that’s the whole point of the gym. This is the gym. (97)

Fellow American, whoever you are, wherever you are: I’m hitting the gym. Want to join me?

Rating: 9/10