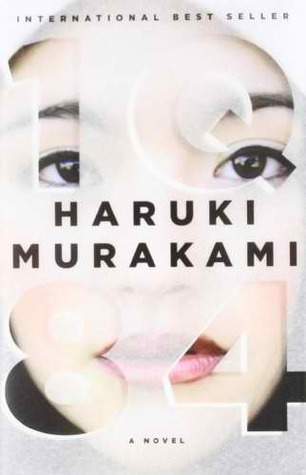

Review: Haruki Murakami’s “1Q84”

by Miles Raymer

1Q84 made a big splash in the literary world when the English translation was released in 2011, but only recently did I get around to reading it. Haruki Murakami is among my favorite living writers, and I always relish the opportunity to return to his weird psychological landscapes.

This nearly-thousand-page novel is comprised of three books, and unfortunately I will be reviewing them as a single work. Books 1 and 2 were on par with the best of Murakami’s other writings, but Book 3 was a major letdown. My dissatisfaction with the last book marred my reading of the other two, and made me feel that 1Q84, all things considered, is a better example of a literary failure than anything else.

1Q84 is the story of Tengo and Aomame, two people living in Tokyo in 1984. They have a shared past, but haven’t seen each other in twenty years. The novel slowly brings them back together after this long period of estrangement, by way of a bizarre sequence of events that won’t surprise any regular Murakami reader. His brand of magical realism is potent indeed, even if it fails to bear fruit in this particular instance.

The big fantastical element in 1Q84 is the Little People, a kind of ideological foil to Orwell’s Big Brother:

There’s no longer any place for a Big Brother in this real world of ours. Instead, these so-called Little People have come on the scene…The Little People are an invisible presence. We can’t even tell whether they are good or evil, or whether they have any substance or not. But they seem to be steadily undermining us. (236)

This is classic Murakami. Rather than a large, overt bringer of doom, we get a small, mysterious power that is “steadily undermining” us. There’s plenty of room here for connections with all forms of modern malaise––a smart tribute to the “Not with a bang but a whimper” school of thought. Sadly, the Little People become less menacing as the story progresses, until we are left thinking that they never actually posed a threat to begin with. Perhaps that is Murakami’s intent, but it feels more likely that he never quite figured out how to to turn his good idea into an effective narrative tool.

Tengo and Aomame make this story hum with possibility and excitement, especially early on. Aomame’s narrative is preoccupied with power dynamics and abuse. Since women are especially vulnerable in a male-dominated world, they must take special care. Aomame explains:

The important thing is to adopt a stance of always being deadly serious about protecting yourself. You can’t go anywhere if you just resign yourself to being attacked. A state of chronic powerlessness eats away at a person. (132)

Aomame trains women in self-defense as part of her profession, but also doles out punishment to abusers in secret, thanks to inspiration and support from a wealthy benefactor. This arrangement prompts the reader to consider whether illegal violence can be morally justified; Aomame’s discipline and daring make her a formidable and alluring character.

Tengo is a former math prodigy who teaches at a cram school while writing fiction on the side. We meet him just as a slick editor is convincing Tengo to accept a dubious assignment: secretly rewriting another author’s novella to improve its chances of winning a literary contest. As is the case with many Murakami protagonists, Tengo soon finds himself embroiled in a web of intrigue that interests him not at all.

Tengo’s quiet life becomes upset by mysterious machinations he doesn’t understand, including some interesting metafictive elements that stem from the rewritten novella. The moon takes center stage as an enigmatic signpost for alternate realities. Sensing disturbances in their respective interpretations of reality, Tengo and Aomame find themselves wondering what constitutes the “real world,” and search for ways to confirm that they are in fact a part of it.

In one particularly curious moment, Murakami seems to harness Tengo’s narrative in order to snipe at critics who complain about “authorial laziness”: “If an author succeeded in writing a story ‘put together in an interesting way’ that ‘carries the reader along to the very end,’ who could possible call such a writer ‘lazy’?” (380). Murakami’s certainly not a lazy writer, but he can be accused of occasionally weaving narratives that are grossly incoherent. It’s unclear here whether Murakami is being playful, or if Tengo’s thoughts represent some genuine resentment on Murakami’s part.

Even though 1Q84 proves more coherent than some other Murakami novels, it fundamentally fails to “carry the reader along to the very end.” I was riveted by this story through the end of Book 2, but Book 3 marked a notable decline in intensity and quality. Tengo and Aomame both retreat into static holding patterns, slackening the pace of an already slow story. They repeat the same thoughts and actions over and over, to the point where their stories become more somnolent than endearing.

Meanwhile, Murakami inexplicably pivots toward one of the novel’s ancillary characters: Ushikawa. Ushikawa has been hired to investigate the relationship between Tengo and Aomame, and while he possesses a kind of repulsive charm, his chapters are little more than recycled mashups of already-familiar information. Sometimes a fresh face can revitalize a long book, but the introduction of Ushikawa as a full-fledged character only embellishes this book’s weaknesses, and throws a few new ones on the heap.

All in all, I found myself sleepwalking through the final 300 pages. The last chapter tied things up more neatly than one expects from Murakami, but by then the damage was already done. My resentment prevented me from enjoying the ending, which I could tell would have been poignant under different circumstances.

In the case of 1Q84, less would have been so, so much more.

Rating: 4/10