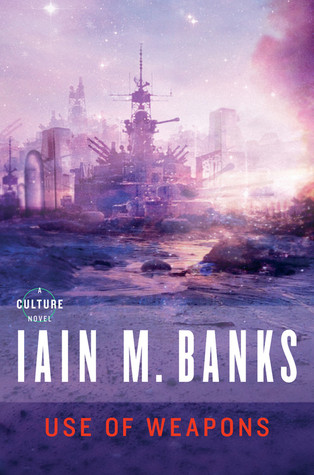

Review: Iain M. Banks’s “Use of Weapons”

by Miles Raymer

Having now read almost all of Iain M. Banks’s Culture novels, I can safely say that they should be required reading for all humans. Was Banks the smartest or most creative science fiction writer of all time? Definitely not. Was his grasp of science and futurism vastly superior to that of his many talented contemporaries? I doubt it. Was his prose the best anyone could hope to find in the science fiction section? Unlikely. But did he create a once-in-a-generation vision of post-scarcity human life that should be honored and explored by all literate apes? I think so.

Similar to other Culture novels, Use of Weapons is a bemusing journey through times and places that appear both familiar and foreign, a tackling of omnipresent human problems platformed on the never-dull contrast between the magnanimous Culture and the poor corners of the galaxy that haven’t yet joined the fold. Banks is fond of victimizing his protagonists, and the central character in Use of Weapons is no exception. Cheradenine Zakalwe’s story unfolds in a teasing, nonlinear fashion, but we eventually learn that this poor sucker was recruited to do Special Circumstances’ dirty work:

In Special Circumstances we deal in the moral equivalent of black holes, where the normal laws––the rules of right and wrong that people imagine apply everywhere else in the universe––break down; beyond those metaphysical event horizons, there exist…special circumstances. (loc. 4236)

Zakalwe soon discovers he is well-suited for this type of labor, and this unfortunate fact condemns him to a difficult but fitting existence, given that he’s already racked with guilt from events in his murky past. Zakalwe is employed and enhanced by the Culture, but not truly a part of it. He travels across the galaxy fighting wars, pulling strings, and generally trying to turn the screws in whatever direction the Culture deems agreeable. He inflicts a lot of pain, witnesses a lot of death and destruction, and saves countless lives. In his own words:

He told her about a man, a warrior, who’d worked for the wizards doing things they could or would not bring themselves to do, and who eventually could work for them no more, because in the course of some driven, personal campaign to rid himself of a burden he would not admit to––and even the wizards had not discovered––he found, in the end, that he had only added to that weight, and his ability to bear was not without limit after all. (loc. 1174)

Zakalwe has a couple of handlers who provide ancillary entertainment––a Culture citizen named Sma and a drone named Skaffen-Amtiskaw––but the overwhelming focus of the book remains on him. As he trudges through torn landscapes, macerated societies, and painful memories of his cataclysmic upbringing, Zakalwe ruminates about the nature of war and trauma. His universe will always be a tortured place where stability is fleeting and conflict dominates the horizon. This makes him a queer but useful tool for the Culture, whose pampered citizens are basically incapable of dealing with anything more serious than finding a costume for an imminent drug party (oh, oh, to be one of those lucky billions!).

As usual, this single Culture novel displays a steady flow of good ideas that most science fiction writers would kill to lay out over an entire career. Banks’s ability to describe perennial moral problems is of the highest caliber, and his talent for situating those problems in the profoundly progressive framework of Culture ideology is even more impressive. Take, for example, this terrifying revelation: After decades, lifetimes, generations of experience and inquiry, the fruit of all our wisdom comes to…utter paralysis:

I don’t know what the right thing to do is; I sometimes think I know too much, I’ve studied too much, learned too much, remembered too much. It all seems to average out, somehow; like dust that settles over…whatever machinery we carry inside us that leads us to act, and puts the same weight everywhere, so that always you can see good and bad on each side, and always there are arguments, precedents for every possible course of action…so of course one ends up doing nothing. (loc. 3942-50)

Or wrap your wetware around the novel’s eponymous passage, which can only inflict the most exquisite and delicate violence on the human imagination:

He saw that which cannot be seen––a concept; the adaptive, self-seeking urge to survive, to bend everything that can be reached to that end, and to remove and to add and to smash and to create so that one particular collection of cells can go on, can move onward and decide, and keeping moving and keeping deciding, knowing that––if nothing else––at least it lives.

And it had two shadows, it was two things: it was the need and it was the method. The need was obvious: to defeat what opposed its life. The method was the taking and bending of materials and people to one purpose, the outlook that everything could be used in the fight; that nothing could be excluded, that everything was a weapon, and the ability to handle those weapons, to find them and choose which one to aim and fire; that talent, that ability, that use of weapons. (loc. 2387-86)

Zakalwe’s tale contains many lessons, the most important being that no living thing is without sin. Life’s original sin is not the result of some moral failing or departure from divinity. It is the simple fact of existence––the jealous perpetuation of an organized collection of matter, fueled by the constant consumption of other, conquered collections of matter, for no purpose other than the maintenance of an already-arbitrary, always-indefensible maw of self-regard. Humans have embellished this charade with delusions of identity and rational justification. It is a sorry state of affairs.

In defiance of the myths we tell about our accomplishments, our ephemeral victories against suffering and discontent, an honest consciousness will always return to the question of its own right to survival, or rather, to the incontestable absence of that right. Try as he might to escape the truth, Zakalwe remains a villain––just like everyone else.

Rating: 9/10

Having now read almost all of Iain M. Banks’s Culture novels, I can safely say that they should be required reading for all humans.

Couldn’t agree more.

Thanks for reading!

I still have Exession and Inversions to read – I’ve come at the Culture series all higgledy-podge. Just read Use of Weapons and now know what the final words of Surface Detail were saying – in fact, what that whole novel was saying, as a layer on top of the Heaven/Hell/life triumverate. Your review of Use of Weapons was quite a wonderful read, thank you. I’m frustrated with Banks’s flying-off-around-the-edges sometimes, but the theme of each Culture novel is so beautifully well-rounded, so all-encompassing that each book affords loads of contemplation. And of course as I can well attest, it’s not important to read the novels “in order” as they are all self-contained with respect to technology in general and the Culture in particular. In fact, my first was Player of Games and I was surprised by each subsequent read that the Culture is always seen from the outside (except the novella State of the Art) – which is rather the point Banks was always making; as a utopian culture, the dynamics are missing for good novelistic structure. After reading 2 Culture books, I read an interview with Iain M Banks who admitted he had a tendency to kill off his protagonists, so I approach each new book with a bit of dread – as a reader, I want to identify with the protagonist, go on their journey, but knowing they’ll probably be dead at the end of the book is a bit of a downer from the outset. However, it’s the over-arching themes that he addresses which make all of Banks’s Culture novels, as previous commenter Douglas Clark said, ‘required reading for all humans’.