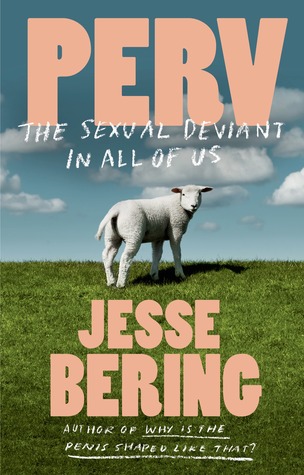

Review: Jesse Bering’s “Perv”

by Miles Raymer

Even if we won’t admit it, I think most people spend quite a lot of time thinking about sexual norms––what they are, where they come from, and to what extent each of us either conforms to or subverts them. Jesse Bering’s Perv invites the reader on a lively journey through historical and current perspectives on what constitutes sexual deviance. The book’s central argument––that harm is the only legitimate measuring stick for the morality of sexual behavior––isn’t unfamiliar to me, but Bering’s enthusiasm and wit, combined with a wealth of balanced research, made reading Perv a thoroughly enjoyable experience.

Perv is essentially a series of essays that all assert the same thing: it shouldn’t matter what turns people on or gets them off as long as nobody gets hurt. Here’s how Bering puts it:

We’ve become so focused as a society on the question of whether a given sexual behavior is evolutionarily “natural” or “unnatural” that we’ve lost sight of the more important question: Is it harmful? In many ways, it’s an even more challenging question, because although naturalness can be assessed by relatively straightforward queries about statistical averages…the experience of harm is largely subjective. As such, it defies such direct analyses and requires definitions that resonate with people in vastly different ways. When it comes to sexual harm in particular, what’s harmful to one person not only is completely harmless to another but may even, believe it or not, be helpful or positive. (21)

This approach didn’t strike me as novel, but it’s good to keep in mind that Bering’s harm principle runs contrary to the sexual worldviews of a significant chunk of my fellow Americans and Earthlings. Bering does an exceptional job of demonstrating the historical and contemporary reasons why humans have bungled the question of how to judge our sexual impulses and actions. Over and over we’ve ignored the harm principle in favor of much more capricious, parochial, and oppressive cultural norms. It’s hard to judge our ancestors too harshly given that they lacked the empirical foundation we modern humans have begun using to update and improve our own attitudes about sexuality. Even so, the historical details are not pretty or easy to stomach; the myriad tales of individuals and groups that have been unjustly persecuted over the centuries are downright depressing.

But Bering doesn’t come to the table without good news. One of the most valuable ideas in this book is the concept of sexual imprinting, which occurs when “a highly circumscribed set of erotic targets is stamped early into the individual’s brain” (122). That’s a fancy way of saying that experiences in early childhood (and sometimes adolescence) can lead to huge differences in sexual wiring between individuals. This is presumably where rare kinds of fetishes, kinks, and sexual orientations are born, as well as more mundane features of sexuality that we think of as hallmarks of “normal” development.

Sexual imprinting is critically important for two reasons: First, it forms a useful bridge between our natural (genetic) predispositions and the experiences we have in the world. As with all forms of human development, sexuality is not a “nature or nurture” affair, but rather a complex and highly individuated product of both influences. Second, sexual imprinting drives home the message that people with “deviant” sexual desires are not somehow “responsible” for those desires. Sexuality isn’t a choice, but rather something that happens to people. Sexual actions are absolutely choices and can therefore be subject to harm-based moral judgments, but no one should be ridiculed or condemned for merely having sexual impulses or thoughts––no matter how abhorrent they might seem. This leads us straight back to the harm principle, solidifying Bering’s assertion that non-harm-based judgements about sexual cognition or conduct are essentially worthless:

One person’s sexual exorbitance is another’s slow Monday morning. In my opinion, the only important point to weigh when trying to decide what is or isn’t sexually appropriate is, again, that of harm. Deviations from population-level averages are useful in helping us to understand the full range of erotic diversity, but as we’ve seen, the issue of what is “normal” or “natural” is as shallow as a thimble when it comes to guiding us about how to behave. Unless we want to invoke the idea of a God who wound up the clockwork setting of an evolved human nature (and there’s certainly no reason to do that), normal is just a number. And it’s one without any inherent moral value at all. (88, emphasis his)

Despite my view that Bering’s central argument is unimpeachable, I have mixed feelings about his style. Bering’s writing is genuinely funny but often needlessly florid. He delights in showcasing his impressive vocabulary at the risk of alienating less sophisticated readers––folks who would probably benefit from the ideas in this book more than anyone else. Content-centered readers will also struggle with numerous paragraphs that are one-third information and two-thirds quippy commentary.

Perv has a strong confessional component that isn’t commonly found in nonfiction. Bering’s personal narratives make useful and concrete contributions to sexological discussions that can feel overly abstract, but he also can’t restrain himself from weighing in with information that most nonfiction authors would keep private in order to maintain a semblance of objectivity. Too often he chooses sarcasm over seriousness, sometimes by injecting personal views such as his personal “ick” factor or religious/political leanings (38-9, 88, 230). Once again, these unnecessary inclusions might undermine the proliferation of Bering’s important message by turning off readers who don’t already agree with him. But this is a minor problem; nobody could argue that this book isn’t authentic, and it’s quite possible that Bering’s eccentricities charm as many or more readers than they drive away.

At its best, Bering’s expressive prose soars to lofty emotional and intellectual heights:

Our new value system would need to be constructed of the brick and mortar of established scientific facts, its bedrock being the incontrovertible truth that sexual orientations are never chosen. It must also have walls of iron to protect us from the howling winds sure to arrive as we move along, walls forges by the knowledge that there is no evil but that which comes from thinking there is so. To guide us forward, we must emblazon every star in the sky with the reminder that a lustful thought is not an immoral act. And our handrails would have to be painstakingly carved from the logic that in the absence of demonstrable harm the inherent subjectivity of sex makes it a matter of private governance. Finally, and most imposing of all, we’d each have to promise to walk this brave new path completely naked from here to eternity, removing this weighty plumage of sexual normalcy and strutting, proudly, our more deviant sexual selves. (232-3)

I can’t imagine a better way of characterizing the great sexual project of the 21st century. Can you?

Rating: 7/10

Good job Miles! You seem spot on in regards to your criticisms and compliments. Initially, I thought Bering was being objective despite his snarkiness, candidness, and other quips, but after reading many of his essays, I have my doubts. Nonetheless, his argument is simple and to the point–what is the harm? This seemed like a good argument at first, but now I realize that just because something doesn’t cause harm doesn’t mean it is welcomed, i.e. a man losing his hair is a good example. It doesn’t cause harm, but most men would like to avoid it anyway. I imagine there is a long list of things that don’t cause harm but that a large part of the population would rather not exist. Thanks for the review. It’s good food for thought, and it was certainly a good read.