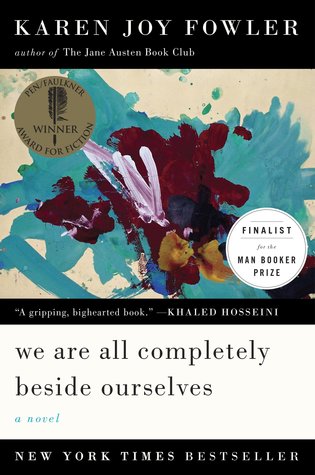

Review: Karen Joy Fowler’s “We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves”

by Miles Raymer

We live in a world shaped by scientific principles, but our understanding of those principles is always less than perfect. As technology and scientific inquiry become ever more embedded in our social and professional lives, it’s important not only to ensure exposure to reliable information, but also to ask how this trend affects the quality of human experience. We have plenty of hard-nosed, data-driven works of nonfiction to inform, warn, and titillate us, but none of them has the same impact potential as a good story. Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves throws humanity’s relationship with science into the messy landscape of modern fiction, revealing our deeply conflicted feelings about the practice that makes modernity hum.

Fowler grabbed me right away with her vivid prose, sardonic tone, and a mysterious premise rooted in familial angst rather than contrived conflict. Rosemary, the book’s narrator, is a quiet young woman with a fragmented memory and some serious emotional baggage. We first meet Rosemary in her early twenties, but soon learn that, as part of a psychology experiment in the 1970s, Rosemary’s father decided to raise her with a “sister”––an infant chimpanzee named Fern. Fern lived as Rosemary’s twin, sharing a home with her parents, older brother, and a handful of graduate students. Then one day, when Rosemary was five years old, Fern disappeared. Seven years later, her brother Lowell also vanished.

Before we can find out what happened to Rosemary’s siblings, we must first delve into the mind of a woman reluctant––or unable––to recall all the pertinent details about her past. Rosemary is an unreliable (but not insincere) narrator trying to understand her own story along with the reader. She is particularly preoccupied with the inadequacies of memory and language: “Language does this to our memories––simplifies, solidifies, codifies, mummifies. An oft-told story is like a photograph in a family album; eventually, it replaces the moment it was meant to capture” (48).

Rosemary’s childhood traumas have stymied her personal development; she has trouble expressing herself verbally and maintaining relationships. Her internal monologue is a loquacious, nonlinear waltz where literary metaphors regularly pair up with psychological and philosophical theories, but her intelligence and verve don’t translate easily to the world outside her head. She is deeply ambivalent about the purposes and methods of science, especially as related to animal rights:

I came to a report on a 1985 break-in at UC Riverside. Among the many animals stolen was a macaque named Britches. Britches’s little eyes had been sewn shut the day he was born, in order to test some sonic equipment designed for blind babies. The plan was to keep him alive for about three years in a state of sensory deprivation and then kill him to see what that had done to the visual, auditory, and motor-skills parts of his brain.

I didn’t want a world in which I had to choose between blind human babies and tortured monkey ones. To be frank, that’s the sort of choice I expect science to protect me from, not give me. I handled the situation by not reading more. (141)

Rosemary’s reaction to this horrifying true story of animal cruelty is a brilliant representation of the misconceptions and difficulties that accompany scientific society. Sometimes science creates a new problem while searching for a solution to an old one. Progress often forces us to choose between undesirable outcomes when there’s no good option. There’s a split between those who practice science and the general public, which has the option to ignore unsavory details (as Rosemary does). When abused, science can become a haven for the worst expressions of human cruelty. We can’t assume that the benefits of science come with no cost, and if we’re open about how research is conducted, we can’t “protect” people from being disgusted or outraged by it.

Fowler smartly problematizes these issues without becoming dogmatic about who’s innocent and who’s guilty. Rosemary’s brother Lowell becomes an operative with the Animal Liberation Front after learning about Fern’s fate. Contrasting their reactions, Rosemary thinks:

Lowell heard that Fern was in a cage in South Dakota and he took off that very night. I heard the same thing and my response was to pretend I hadn’t heard it. My heart had risen into my throat, where it stayed all through Kitch’s horrible story. I couldn’t finish my Coke or speak around that nasty, meaty, beating lump. But as I’d biked home, my head cleared. It took me all of five minutes to decide it wasn’t such a bad story, after all…Lowell, I thought, was capable of leaping to some crazy conclusions. (125)

Again, Fowler cleverly reveals the mental mechanisms we use to cope with modernity’s omnipresent deluge of distasteful information. Most of us do not become radicalized in the face of injustice. We grimace, we gasp, we feign dismay long enough to lose our appetites. And then we tell ourselves a story, one in which veracity is less important than salutary effects. If we condemn Rosemary for her inaction, we must also condemn ourselves. So we love her instead, so we can keep loving ourselves.

Lowell’s not exactly an inspirational figure, either. After abandoning his family for a life on the run, his experience is marked more by disaffection and paranoia than heroism. No one deals with the situation well, and there’s plenty of blame to go around.

As poignant and thoughtful as Fowler’s story is, I found it difficult to care much for any of the characters other than Rosemary, even when I knew I was supposed to. This general insouciance also extended to Fern, even as she suffered tragic forms of victimization. While the writing was great to the end, I disengaged somewhat after learning what had happened to Fern and Lowell. It’s unclear whether this a failure of Fowler’s writing or the result of my well-known empathy gap, but I suspect the latter is more likely. It’s also possible that I don’t want face up to my personal status as one of the silent majority––a meat eater who occasionally pays lip service to animal rights without ever doing anything about it.

Whatever the case, I’m convinced that We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves is a useful and interesting book. My takeaway message was that, even as we strive to expand our knowledge of the natural world, we should never naively take elements of nature out of context. In the end, Rosemary faces up to this reality:

There had been other incidents that my parents swore I knew about and had even witnessed, though I have no memory of them…One of the grad students had been badly bitten in the hand…she [Fern] had flung Amy, a grad student she adored, against a wall, a distance of several feet…Her [Fern’s] remorselessness…had shocked me to the core. So this is what I should have said to Mom; this is what I meant to say––

That there was something inside Fern I didn’t know.

That I didn’t know her in the way I’d always thought I did.

That Fern had secrets and not the good kind. (269-70)

Of course Fern has secrets. She is a member of a completely different species, foolishly dragged into a charade she can neither understand nor properly appreciate. Rosemary’s parents, and the ideological justifications that drove them, are the unintentional villains here. Raising a chimpanzee in a human family is a stupid proposition, even in cases where the animal might otherwise perish. The pain Fern experiences when re-introduced to her own kind could have been completely avoided had some idiot humans resisted the urge to raise her as something she could never be.

We can’t stop doing science, and we shouldn’t; it’s the best mechanism we have for expressing our natural curiosity, and it’s an incomparable tool for improving human life. But we should remember that science is always personal––if not for you, then for someone else.

Rating: 8/10