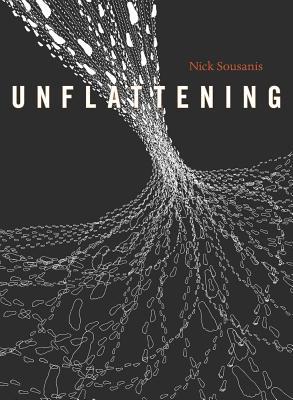

Review: Nick Sousanis’s “Unflattening”

by Miles Raymer

Nick Sousanis’s Unflattening has the look of a graphic novel, but it’s actually a group of interrelated philosophical essays presented in comic book form. This stunning work of art presents a gauntlet of brain-teasers that challenge our assumptions about the nature of human perception and understanding. Sousanis’s central message––that we should learn to see from multiple perspectives at once instead to searching for the “correct” outlook––is an important one, despite not being particularly novel. The written text is somewhat vague and highly repetitive, but Sousanis more than compensates for this weakness with visual creativity. The artwork in this book is brilliantly conceived and exquisitely rendered.

Sousanis defines “unflattening” as “a simultaneous engagement of multiple vantage points from which to engender new ways of seeing” (32). Drawing from the works of scientists, philosophers and artists, Sousanis creates a journey through three-deminsional space rendered on two-dimensional surfaces. He explores the ironic tension between the expansion of scientific knowledge and the intellectual barriers that arise between different areas of study, and also demonstrates a keen understanding how relationality affects meaning:

Meaning is…conveyed not only by what’s depicted, but through structure: the size, shape, placement, and relationship of components––what they’re next to and what they’re not, matters. (Orientation too.) (66)

Sousanis’s perspective is deeply indebted to American philosopher John Dewey, who he cites more than once, as well as to Mark Johnson and George Lakoff, two inheritors of Dewey’s tradition. Having studied Dewey under Johnson’s guidance during my undergraduate education, I was delighted to see these names woven into such an unusual and boundary-breaking treatise. Sousanis has taken their philosophies to heart and put them to excellent use.

Sousanis rightly suggests that upending our habits of perception can bring about expansions of consciousness, and thinks that comic books––with their trademark mixture of words and images––are in a unique position to precipitate such changes. I believe he is correct about this, although I suspect his assessment of comics’ potential may be slightly inflated. He claims that comics provide “a means to capture and convey our thoughts, in all their complexity, and a vehicle well-suited for explorations to come” (67). Someone well-versed in the mechanisms of perception should be skeptical of any artform that purports to portray thoughts “in all their complexity.” Comics can definitely challenge the mind in a special way, but they have their limitations as well, just like any medium of art. Anyone who claims to comprehensively capture any thought––let alone a series of thoughts that might coalesce into an idea––is overstepping.

Sousanis also stumbles slightly in his depiction of how the brain builds autobiographical narratives. Discussing his teenage self’s invention of a superhero called “Lockerman,” Sousanis digs into his childhood memories for a theory of the superhero’s origin:

Lockerman’s true origins, I came to realize, sprang from my early fascination with keys and locks; my brother’s tall tales about what lay within the kitchen cupboard and lurked behind the attic door (which remained shut), as well as the wonderlands accessed by ordinary portals: rabbit holes, looking glasses, and wardrobes. (93)

This lovely notion not only lacks verification, but defies verification altogether. Sousanis fails to point out the critical caveat that the imaginative origins of an idea like Lockerman are always opaque, both to their creators and anyone else. What he is describing here is an autobiographical narrative generated by his brain after the fact. Sounsanis is trying to make sense of himself, and in doing so he links up the idea of Lockerman with specific memories, constructing an intelligible story whose primary function is to fill gaps in his identity, to render his self a unified entity that has persisted through time. Does this mean that Lockerman definitely didn’t spring into existence in the way Sousanis claims? Certainly not. But neither is it accurate to say he “discovered” Lockerman’s true origins. Sousanis has concocted a comforting and graspable story, but with no certainty of its veracity.

There’s a final problem in Unflattening that I think needs addressing. Sousanis is adept at teasing out the multiple perspectives that can be brought to bear on a given object or idea, but his book doesn’t satisfactorily teach us how to agree about anything. It’s all well and good to teach ourselves to seek out unacknowledged points of view, but when it comes time to decide how to turn our concepts, experiences and values into action, people have to have at least enough common ground to hear one another, negotiate and compromise. Sousanis displays a good grasp of how the “gulf of mutual incomprehension” can stifle communication, and puts forth a possible solution: “In recognizing that our solitary standpoint is limited, we come to embrace another’s viewpoint as essential to our own” (38). Okay, but is internalizing an alternative perspective necessarily the same as condoning it, as thinking it deserves to be acted upon? I don’t think so. We’re still left with the problem of sorting out “valid” or “relevant” perspectives from “invalid” or “irrelevant” ones. (It’s hard to fault Sousanis too much for falling short here; in my experience, nobody else can resolve this problem, either!)

Having enjoyed my usual pokes and prods, I want to reiterate just how fascinating and singular this book is. I’ve definitely never read anything like it, and I think it’s a useful text for those familiar with the philosophy of perception as well as neophytes. Unflattening is a marvelous testament to the fact that visual art can explore regions of thought that are unavailable to the written word alone.

Rating: 8/10