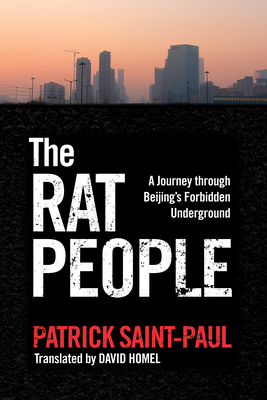

Review: Patrick Saint-Paul’s “The Rat People”

by Miles Raymer

In 2014, Evan Osnos reflected on the time he spent as a foreign journalist in China:

The longer I lived in China, the more it seemed that people had come to see the economic boom as a train with a limited number of seats. For those who found a seat––because they arrived early, they had the right family, they paid the right bribe––progress was beyond their imagination. Everyone else could run as far and fast as their legs would carry them, but they would only be able to watch the caboose shrink into the distance. (Age of Ambition, 271)

Patrick Saint-Paul’s The Rat People is about the Chinese citizens who missed that train. This informative book reveals the hidden lives of Beijing’s shuzu, or “rat people.” These are migrant workers (mingong) who have undertaken “the greatest human migration in history,” journeying by the tens of millions from rural China to seek opportunity in the country’s booming urban centers (14).

Saint-Paul’s reporting is solid, but the book lacks references and an index; including one or both of these features would have improved it. Even so, his detailed interviews combined with David Homel’s translation bring clarity and intimacy to these tragic stories, reminding readers that progress always comes with a cost. In the case of 21st-century China, the human cost of progress is extremely high:

These are the underlings of Chinese prosperity. Their lives are no fairy tale… The wealth of the entire nation that is poised to become the number one world economy is built on the shoulders of these laboring masses…The forgotten faces of growth, they are often exploited and considered second-class citizens. Their fate can be compared to the working class in European cities during the industrial revolution of the nineteenth century. Seven million mingong, out of 21 million inhabitants, contribute to the exuberant growth of the capital city, where they have come in hope of a better life, transforming the country into the global economic powerhouse it is now. Meanwhile, they live underground––literally…In Beijing, the tribe lives in countless basement rooms, and even in sewers. More than 1 million of them, according to estimates, subsist in Beijing’s belly. With no hukou, or residence permit, the paper needed to access all forms of the social safety net, including health insurance and schools for their children, they don’t have even the most basic rights. Stuck at the bottom of the ladder, their only hope is to move up a rung or two. (14-5)

In a series of grim vignettes, Saint-Paul describes the lives of various shuzu he spoke to between 2013 and 2016 (the book’s original publication year in France). The typical narrative of a shuzu begins with the difficulties of rural life in modern China. Unable to make more than starvation wages working on farms, and under the constant threat of land being expropriated by government officials, most young adults move to the city. There they live in subterranean squalor, work long hours at difficult jobs, and earn just enough to live and send meager support home to their families. The very best they can hope for is that their children will have a slightly better life than they did, although for many even this modest goal ends up being out of reach. Some give up the idea of having kids altogether, realizing that having a family will likely condemn them to a lifetime of merely scraping by or worse.

Most heart-breaking are the stories of liushou ertong, abandoned children who “have been sacrificed on the altar of Chinese economic growth” and “wander through childhood and adolescence with no one to look after their health, be it physical, emotional, or psychological” (87). Death by accident and suicide are common throughout the rural areas where liushou ertong live, with overwhelmed grandparents unable to fill the parental vacuum.

Even college-educated citizens have a hard time finding work. Nearly a third remain unemployed one year after graduation, and more than two-thirds make salaries no greater than those of migrant workers (111). “Even if they go to the large urban centers to improve their living conditions,” one economist comments, “they will still end up as part of the underclass” (112).

Despite the inhumane conditions in which they live and work, many shuzu display impressive grit and optimism. For some, their positive attitudes appear to be nothing more than psychological coping mechanisms, but their perseverance is nevertheless inspiring. As Saint-Paul points out:

The nickname “rats” is not entirely pejorative…Chinese astrology describes rats as ambitious, determined, impassioned, intelligent, lively, persuasive, energetic, resourceful, loyal, with a good sense of humor, and generous with friends and family. (188)

All of those adjectives apply in one way or another to the shuzu––a group blessed with unique energies but forsaken by luck and forgotten by society. “Surviving the Beijing hierarchy at the very bottom of the ladder,” Saint-Paul writes, “is a complex undertaking that demands extraordinary adaptive powers mixed with inexhaustible fatalism” (38).

The shuzu‘s collective effort is the engine powering China’s increasing dominance on the world stage, but precious few enjoy a fair share of the prosperity they help to create. Saint-Paul renders the shuzu‘s mostly-futile efforts to improve their lives even more disturbing by contrasting them with the conspicuous consumption of Chinese elites. These members of the ultra-upper class consolidate their wealth and power with each passing year, exacerbating already-extreme socioeconomic inequality in ways that may prove unsustainable:

No one is willing to place a bet on the party’s life span. It could go into overtime for several more decades––or suddenly stumble and fall. No doubt, if that day dawns, the rats will be first to emerge from their holes to bring down a ruling party that never did anything for them. (185)

The Rat People is a good book about an important issue, but overwhelmingly sad. The waste of human potential is vast and incalculable. For those seeking a companion book about similar issues in America, I recommend Chris Arnade’s Dignity.

Note: I was fortunate to receive a free copy of this book in exchange for an honest review.

Rating: 7/10