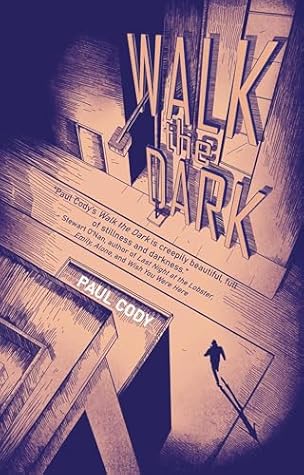

Review: Paul Cody’s “Walk the Dark”

by Miles Raymer

Disclosure: I received a free copy of this novel from the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

Paul Cody’s Walk the Dark is a slow, strange novel that unfolds through two alternating sequences. The protagonist and narrator, Oliver Curtain, tells his life story via a series of chronological flashbacks, starting from early childhood and terminating in late adolescence. Between these flashbacks are chapters set in the present, where Oliver is serving out the 29th year of a long sentence in a New York prison. The obvious question of what landed Oliver in prison is an excellent hook, which Cody follows with a promising yet restrained narrative that never quite gets off the ground. Cody is a talented writer whose detailed imagery and precise prose have no trouble evoking the reader’s emotion, but the quality of his story doesn’t match the writing.

In my view, Walk the Dark is best understood as an homage to the forgotten poor in American society. Oliver’s upbringing is a tragic tapestry of factors that dominate the lives of America’s least fortunate citizens: prostitution, addiction, poverty, and complete disengagement from education and community life. Oliver’s mother is an energetic and loving but wildly irresponsible parent who exposes him to sex work and drugs at an extremely young age. The male figures in Oliver’s life are the blurry torrent of men who drift in and out of his mother’s bedroom, some nicer than others. And aside from his mother’s best friend and a girl he becomes friends with in his early teens, Oliver has no other major attachment figures in his life. Predictably, he drifts through his days in a blissed-out haze fueled by the steady stream of alcohol and prescription drugs provided by his mother and her best friend. As he ages, the bliss wears off, replaced by a cold combination of numbness and unbreakable habit.

Oliver’s one distinguishing feature is his practice of “walking the dark” at night. He wanders around his neighborhood when everyone is asleep, gazes into homes, and fantasizes about the lives of people who are better off. Later, he begins actually entering some of these homes, but never with criminal intent; he merely wants to get closer to the material trappings and homey vibes of “normal” people. The intense loneliness that suffuses these scenes is heartbreaking.

Oliver’s present-day scenes in the prison are less captivating than the flashbacks, but they do add an additional layer of depth to the novel’s mélange of American decay. Cody captures the quiet, desperate, and often-undignified lives of Oliver and his fellow prisoners, reminding readers of the massive population of discarded American men that languish in confinement. More than any other, this aspect of Walk the Dark reveals Cody’s noble attempt to illuminate stories that usually vanish into unremembered darkness. And more than any other, this aspect of Walk the Dark renders it a worthy piece of American fiction.

If I could improve this novel in one way, I’d want it to be somewhat more conventional. The unconventional elements of Cody’s writing shine, but I think they’d be better paired with more familiar plot beats. Maybe other readers would disagree, but by the end I was frustrated by the classic feeling of “this isn’t going anywhere!” We do finally get an explanation for why Oliver ended up in prison, but it didn’t have the impact I was expecting and craving. Still, I enjoyed the time I spent “walking the dark” with Oliver, and am grateful to Cody’s publisher for sharing this novel with me.

Note: This review was originally published on November 25th, 2024. The original was lost in a database corruption event but I was able to republish on the date below.