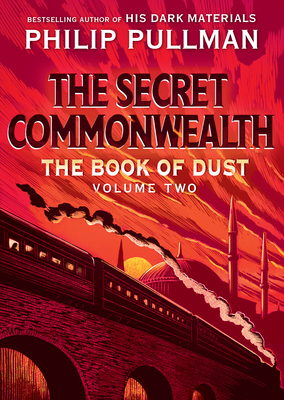

Review: Philip Pullman’s “The Secret Commonwealth”

by Miles Raymer

As a huge fan of Philip Pullman, I take no pleasure in reporting that The Secret Commonwealth is a massive disappointment. This novel, which begins every bit the worthy successor to Pullman’s marvelous His Dark Materials trilogy, slowly and tragically dissolves into a narrative so desultory and dull that it may as well not exist. Or it’s brilliant in a way I can’t comprehend––but I don’t think so.

Rarely do I feel the need to take vengeance on a novel when reviewing it, but this one brought me to a point of deep, painful resentment. The primary reason is that, unlike most bad books, the opening act displays incredible promise. La Belle Sauvage, the first volume of The Book of Dust, was a strange and dark tale with a lot of potential, and the first couple hundred pages of The Secret Commonwealth honor that potential, proving as good as anything Pullman has previously written. The story is mature and unsettling in a fashion that departs from his first trilogy, and the book starts off with a solid balance of plot-based and character-driven energy.

Lyra, now twenty years old, must deal with the consequences not only of her own personal journey as an adolescent, but of events that took place in her infancy. The relationships between Lyra and those seeking to cultivate her incipient adulthood are touching, and the older versions of the main characters from La Belle Sauvage are well-crafted. Watching them interact with Lyra is a genuine pleasure.

This pleasure is contrasted heavily by Lyra’s intriguing and disturbing arguments with her daemon, Pantalaimon (Pan). The Secret Commonwealth reveals new dynamics between humans and daemons, namely a host of ways in which people and their daemons can become separated. These operate as relatively successful metaphors for how our social relationships fluctuate over time and how people can become internally conflicted and alienated from aspects of their own personalities. Lyra and Pan become embroiled in a philosophical dispute over the nature of truth, and whether it is a product of strict objective rationalism or of pure subjective imagination. Their squabbling over this false dilemma becomes quite vicious, eventually leading to a dramatic but somewhat baffling estrangement. Unfortunately, the quality of this conflict degrades as the novel progresses, along with everything else.

Pullman is also preoccupied with “the world of hidden things and hidden relationships”––an animistic magical realm from which the novel derives its title (389). He often hints at the possible significance of “the secret commonwealth,” but doesn’t deliver enough detail to establish its value as a narrative device. This noncommittal attitude toward its own ideas permeates The Secret Commonwealth in a way that feels almost intentional, as if Pullman thought being intellectually wishy-washy would somehow improve things.

For as long as Lyra and her companions stick around in Brytain (Pullman’s fictional version of Britain), the novel holds together fairly well. But once they hit the road and split off into separate subplots, the story swiftly disintegrates into a plodding caravan of interactions with seemingly-inconsequential and mostly-uninteresting new characters. The main characters don’t interact nearly enough, and none of their individual journeys proves enlightening or more than superficially exciting. The novel is more than 600 pages, and in the last few hundred the story becomes increasingly rudderless, and––worst of all––boring. There is nothing in the way of a compelling climax, and the book terminates at a point that would constitute rising action in a tighter, more focused tale.

Given that The Amber Spyglass is by far my favorite volume of His Dark Materials, I am cautiously optimistic that Pullman’s conclusion to The Book of Dust will be worth reading at worst and capable of salvaging the series at best. But as it currently stands, The Secret Commonwealth imperils Pullman’s reputation as a master storyteller.

Rating: 2/10