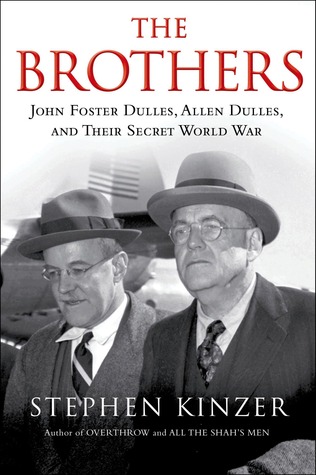

Review: Stephen Kinzer’s “The Brothers”

by Miles Raymer

Anyone who takes an honest look at American history must grapple with our shameful record of foreign intervention. As with slavery, Native American genocide, and many other homegrown atrocities, we must confront these unseemly aspects of our past in order to avoid similar mistakes in the future. Stephen Kinzer’s The Brothers offers a powerful analysis of American arrogance and stupidity in the wake of World War II––one that is surely edifying even if it is also flawed.

Kinzer’s eponymous brothers are John Foster and Allen Dulles, progeny of early 20th-century American elites who rose to power during the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower. Kinzer posits that these two men, very different in their mannerisms but perfectly aligned in their politics, exerted a strong influence on American foreign policy and squandered an invaluable opportunity to lead the world responsibly in the postwar era.

Deeply researched and well-written, The Brothers demonstrates how the Dulles brothers contributed to three insidious dynamics that still plague American politics today. The first of these is the bald application of religious zealotry to the notion of what America is and ought to be. Raised by a fervent Presbyterian family with immense privilege and access to high society, both brothers developed a simplistic worldview unfettered by nuance and self-doubt:

They were raised in a parsonage and taught from childhood that the world is an eternal battleground between righteousness and evil. Their father was a master of apologetics, the discipline of explaining and defending religious belief. They assimilated what the sociologist Max Weber described as two fundamental Calvinist tenets: that Christians are “weapons in the hands of God and executors of His providential will” and “God’s glory demanded that the reprobate be compelled to submit to the law of the Church.” (116)

People who see the world this way tend to conflate financial success with virtue, so it’s no surprise that the Dulles brothers cut their teeth in the world of corporate finance. After completing their Ivy League educations, they began working for the august law firm Sullivan & Cromwell. There, they helped America’s biggest corporations extend their reach in a swiftly-globalizing world, consolidating resources and helping America’s richest captains of industry become even richer:

Although not plutocrats themselves, they spent their lives serving plutocrats…Their life’s work was turning American money and power into global money and power. They deeply believed, or made themselves believe, that what benefitted them and their clients would benefit everyone. (116)

The world that had shaped them was based on the premise that powerful countries, especially the United States, had the right to set the terms of their commerce with other countries whose resources and markets they coveted. (160)

These two perspectives complemented the emerging ideology of American exceptionalism, which mingled all too easily with religious surety and corporate expansion. As the last superpower standing after the global trauma of World War II, the idea that America was ordained by God to lead humanity into a new era of peace and prosperity fit the moment. John Foster and Allen Dulles embraced this mission, utilizing their roles as Secretary of State and CIA Director to covertly interfere with less powerful nations. Each of these misadventures was given Eisenhower’s blessing, which invariably took shelter in the oft-false promise of Communist containment.

The meat of Kinzer’s text describes in dismaying detail how the Dulles brothers undermined fledgling governments in Iran, Guatemala, Vietnam, Indonesia, Congo, and Cuba. Over and over, they passed up opportunities to negotiate and learn in favor of decisive and injudicious action:

Foster and Allen never imagined that their intervention in foreign countries would have such devastating effects––that Vietnam would be plunged into a war costing more than one million lives, for example, or that Iran would fall to violently anti-American zealots, or that the Congo would descend into decades of horrific conflict. They had no notion of “blowback.” Their lack of foresight led them to pursue reckless adventures that, over the course of decades, palpably weakened American security. (314)

Of the numerous ironies that can be plucked from the Dulles brothers’ bouquet of meddling, perhaps the most profound is that they often deposed leaders who sought to emulate the American Revolution’s struggle against colonialism. Their Cold War blinders––made comfortable by their religious convictions––led them to repeatedly reduce complex international conflicts to mere skirmishes between unalloyed American goodness and a mercurial red menace.

There is no doubt that The Brothers has a worthwhile tale to tell, but even so I have a few problems with Kinzer’s telling of it. Kinzer has a clear agenda, which is to deface the American intelligence apparatus and paint the Dulles brothers as blundering, unreflective jerks. In his singular pursuit of these goals, Kinzer doesn’t make much of an effort to entertain opposing points of view. He doesn’t seem to entertain the possibility that the CIA has ever done (or could ever do) anything good, and given the complexity of international affairs and the difficulty of intelligence gathering and operations, this makes him seem more biased than a historian generally ought to be.

Finally, I can’t condone the point of analysis with which Kinzer closes. Speculating as to why the Dulles brothers acted as they did, Kinzer claims:

They did it because they are us. If they were shortsighted, open to violence, and blind to the subtle realities of the world, it was because those qualities help define American foreign policy and the United States itself.

The Dulles brothers personified ideals and traits that many Americans shared during the 1950s, and still share. They did not colonize America’s mind or hijack United States foreign policy. On the contrary, they embodied the national ethos. What they wanted, Americans wanted. (323)

This assertion––one in which Kinzer seems to believe strongly––is at best a half-truth. Much of his own research belies it, especially the ways in which the Dulles brothers and their minions employed manifold forms of subterfuge to conceal their actions from the American people. Kinzer often comments that critical details of the conflicts he describes didn’t become public knowledge until decades later, and yet seems comfortable assuming that Americans would have happily gone along with the Dulles brothers had they known all the facts.

Perhaps I am naive, but I refuse to believe the Dulles brothers did nothing more than channel America’s collective desire to dominate and manipulate. It is impossible to deny that their values and instincts overlapped with that of their fellow citizens, but blowing up their particular flaws and failings in order to impugn the motives of an entire generation seems a bridge too far.

Rating: 7/10