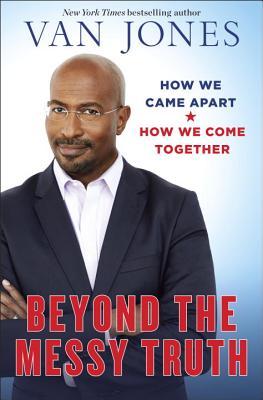

Review: Van Jones’s “Beyond the Messy Truth”

by Miles Raymer

In this era of increasingly putrid political division, there are lots of books out there attempting to diagnose America’s problems and suggest workable solutions. And although I’m not convinced that Van Jones’s Beyond the Messy Truth is necessarily the best of them, if I had the ability to force all Americans to read this book, I would probably do it (very un-American, I know). Beyond the Messy Truth is an intelligent, stirring, and no-nonsense exploration of, in Jones’s words, “How We Came Apart, How We Come Together.”

Despite his liberal partisanship (which he admits openly), I think Van Jones qualifies under my definition of a national hero: someone who works tirelessly in a challenging environment for the betterment of life for all Americans. That last part is crucial; despite disagreeing with conservatives on most issues, Jones exhibits not only an understanding of and respect for them, but also a genuine affection that bespeaks true patriotism––the kind that values our common humanity and heritage as Americans over and above all else. Jones groks the power and indispensability of political coalitions, and knows that strong coalitions can never be built or sustained by people who agree with each other about everything. This short book’s every intimation is shot through with an urgent message, which I think is best captured in these two passages:

Of this I am sure: we need the best ideas from all sides to get to the best solution. Our constitution is a product of passionate disagreement among strong advocates for different positions and constituencies. Innovation does not come from insular agreement but from individuals with different ideas coming together to solve problems using all the tools and ideas at their disposal. As we tackle our country’s most pressing problems, we need intelligent, dedicated people on both sides. (63)

Working together in this way is not easy, but it is what our country desperately needs. In the end, the promise of America is liberty and justice for all. My fellow liberals are so focused on justice we too easily forget about liberty. Conservatives can be so committed to liberty that you become blind to cases where injustice curtails freedom. We need each other. We cannot improve this country alone. If we focus only on winning elections, we end up demonizing the other side. If we focus on solving problems, we’re forced to build bridges. To build bridges, we must listen to each other. When we listen to each other, both sides change and grow. We find ways to disagree without disrespecting each other. As we better articulate our visions and solutions, we find points of tension––but also points of cohesion. We are forced to defend our beliefs to people who disagree with us, which makes them stronger and reveals the cracks. This is what America needs, and it will take contributions from all of us to get to a better place. (89)

This American truth seems almost trite when stated so plainly, and yet we are living through a moment when many partisans on both sides of the political spectrum are likely to scoff at Jones’s suggestion that liberals and conservatives need each other. That reality makes this book a lot more important and interesting than it would be in “normal” political times.

In service of this unifying message, Jones sets out first to highlight the many ways in which Americans from different backgrounds and political tribes are letting each other down, and have been for a long time now. Jones directly addresses liberals and conservatives with two open letters designed to persuade each side that, despite possessing legitimate core values, both camps are complicit in creating and exacerbating political dysfunction. He rightly criticizes liberals for being too thin-skinned when dealing with opposing perspectives:

We need to develop the emotional strength and resilience to reengage intelligently and constructively with the half of America that sees things very differently than we do. It takes a lot of inner work, community support, and maybe a few Jedi mind tricks to deliberately and skillfully place ourselves in conversation with people whose ideas, assumptions, and attitudes often wound us. But our present strategy of retreating further and further into self-affirming liberal echo chambers has backfired in a big way…We have to be wary of losing that natural, openhearted quality, of abandoning our traditional commitment to doing right by all. Otherwise, even when Trump is stumbling politically, he is still winning––spiritually. (27)

As a person who has grown increasingly uncomfortable labeling himself a “liberal” over the last couple years precisely because of this problem, it is a welcome relief to see an avowed liberal direct this kind of compassionate criticism toward his own side.

Another key critique Jones levels at contemporary liberals is the glaring contrast between their obsession with internecine sociocultural deconstruction and their often-ineffectual efforts to construct lasting political change:

We must have a ceasefire in the “who’s the wokest of them all” war. We cannot win against the worst of the right if all of our best weapons are pointed at one another. Right now, too many of us seem to approach liberal causes and conversations mainly by looking for ways to show other progressives what they are doing wrong. Too many of us can deconstruct everything but can’t reconstruct anything and make it work. Too many of us know how to run a protest against the adults on our campuses but don’t know how to run a program for children in our neighborhoods. Too many of us are great at opposition but awful at proposition. Too many of us know just enough critical theory to critique everything but don’t have the practical skills to make anything function at the level of our high standards. Too many of us know how to march against an elected official but not how to elect one. Too many of us know how to call people out but don’t know how to lift people up. And this reality creates internal dangers as real as anything we face externally. (54)

If left unabated, these “internal dangers” will take modern liberalism down the same road that was painfully traversed by mainstream conservatives and the Tea Party during the Obama era. This process appears already well under way, so responsible liberals like Jones ought to be doing whatever possible to slam the breaks and reverse out of the swamp of their own self-righteousness before it swallows them. Beyond the Messy Truth represents an excellent step in the right direction.

Jones has plenty of tough love for conservatives to complement the chiding of his fellow liberals. One of his main points is that conservatives have forgotten and even denied the important counterbalance that liberalism plays and has always played in American life:

Conservatives want policies that that bolster economic liberty and free-market enterprise, but America cannot be great if we do only things on which corporations can make a nice profit. You need liberals to point out key differences between private goods and the public good––and to raise questions about whether private companies are always in the best position to meet the needs of all citizens, especially the poorest and most vulnerable, who cannot pay. Conservatives want to limit the size of government, but you need liberals to remind you that clean air, clean water, safe products, inspected food, nonlethal workplaces, and smog-free cities are all products of government protection––which your constituents like quite a bit…I will keep working to beat you on Election Day. But I don’t want you to stop being conservative. I’m not trying to convince you to come around to “my side” of things. What America needs in the age of Trump is not fewer of you but instead more and better conservatives with the conviction to stay true to your core values. (65)

Importantly, Jones’s approach undermines a scary idea that has become something like gospel in some liberal circles: All we need to do is get rid of or permanently marginalize these conservative idiots, and all our problems will be solved! Jones sees the toxicity inherent in this attitude, and instead seeks to persuade conservatives to double down on the better angels of their nature rather than trying to bully them into becoming different people.

The central goal for conservatives, Jones argues, ought to be turning the Republican party away from its wealthy overlords and back toward the interests of regular Americans:

You have poor people in your party in red states and red counties. But you haven’t done much for them. You accuse the Democrats of letting down our poor urban voters. But the modern conservative movement is structured to ignore its poor rural and suburban base in the same way. Sooner or later, your constituents will realize that you are not building anything, that you are not promoting their interests. In the short term, potshots at liberals and refusals to work on bipartisan legislation can curry favor with Republican activists and their media boosters. But at the end of the day, ordinary conservatives––maybe people like you––are being left behind. (88)

Although Jones’s analyses of American liberalism and conservatism are neither exhaustive nor flawless, I think he does a terrific job of giving both sides a well-deserved scolding while simultaneously offering a warm handshake of encouragement and the promise of spirited collaboration.

Beyond the Messy Truth isn’t all theory. Jones effectively utilizes his past experiences to demonstrate how the power of personal connection will always trump political partisanship in the right circumstances. He describes two unlikely relationships with conservatives––Professor E. Jerald Ogg, Jr. and Newt Gingrich––that taught him about the character of conservative intelligence and the importance of finding common ground across party lines. Jones also recounts his heartwarming friendship with Prince, his musical hero, who bolstered him through difficult times and inspires him even in the wake of a tragic death:

I’ve witnessed humanity united, even momentarily, by one man striking a single note on a guitar. I believe that everybody has a note inside that they can strike, which can resonate beyond their own skin color or political ideology. They may do it through community service. They may do it through their profession. They may do it through parenting. But everyone has that something, that spark, and we have a responsibility to offer it to the world. (137)

Live music has played a critical role in the development of my personal relationships as well as my ethical outlook, so this passage “struck a chord” with me. The project of bringing Americans back together, which Jones calls “The Beautiful Work,” can be summed up as the means by which we can help our fellow Americans––regardless of race, class, gender, etc.––learn how and when to strike their unique notes in the most rewarding and meaningful ways.

Jones gives four prescriptions for enacting The Beautiful Work, all of which are relatively uncontroversial from a sociocultural perspective but politically intractable due to the sclerotic nature of our national government. Jones says that liberals and conservatives should come together to (1) fix the justice system, (2) end the addiction crisis, (3) create more hi-tech jobs, and (4) create more clean energy jobs. These sections are less inspiring than other parts of the book, but they offer pragmatic, bridge-building solutions to serious problems. I see these recommendations not as a comprehensive plan for fixing America, but rather as fruitful starting points for forming the coalitions necessary for such a plan to be conceived and executed.

Jones’s parting sentiment is yet another insight that we should all take to heart:

From the very beginning of this country, America has been two things, not one. We have our founding reality and our founding dream. And the two are not the same. Our founding reality was ugly and unequal. Nobody can deny that…But that’s not all America was, even at the start. And that’s not all we are now…We are that rainbow-hued people, unique on this earth, who contain in our multitudes every color, every faith, every gender expression and sexuality––every kind of human ever born. And we are living together, in one house, under one law…At our best, our mission is simple. For more than two centuries, we have been working to close the gap between the ugliness of our founding reality and the beauty of our founding dream…That’s who we are. That’s what we do. What’s what makes us Americans. (185-7)

If every American made a sincere effort to heed these sentiments and bear them out with compassionate action, there is no doubt in my mind that this country would immediately begin to transform itself into a place far more representative of our founding dream. I’m grateful to Van Jones for his many years of passionate activism, and for sharing his experiences and ideas in this book. I am proud to be one of his fellow citizens.

Rating: 8/10