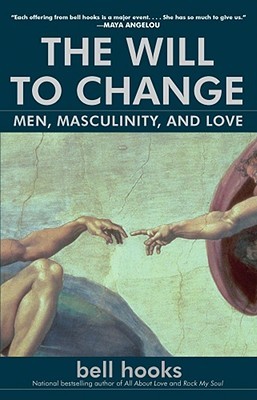

SNQ: bell hooks’s “The Will to Change”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

bell hook’s The Will to Change is a work of feminist philosophy that seeks to articulate and subvert the patriarchal constraints that make it difficult for men to give and receive love. “Masses of men have not even begun to look at the ways that patriarchy keeps them from knowing themselves, from being in touch with their feelings, from loving,” hooks writes. “To know love, men must be able to let go the will to dominate. They must be able to choose life over death. They must be willing to change” (xvii). Covering a range of topics––including the nature of male identity, violence, sexuality, professional life, and pop culture––hooks presents keen critiques of modern male dysfunction as well as hopeful visions for new kinds of masculinity that can escape and reconfigure outdated models of manhood.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- This is my first time reading hooks, and right off the bat I was impressed with her writing. Her prose is straightforward and passionate, intellectually complex without becoming inscrutable. I found many sections of the book to be emotionally moving and resonant with my lived experience; hooks demonstrates an excellent understanding of how patriarchal oppression operates in the lives of modern men.

- I also enjoyed and admired the personal touch that hooks brings. The book contains many intelligent and honest observations from her family and love life that help to illustrate how her theoretical positions play out in actual human relationships.

- hooks’s central thesis is one I can really get behind. She asserts that helping men and boys flourish is everyone‘s job, requiring cooperation from both genders and all members of society. At the same time, she locates the onus for change squarely where it belongs: on the shoulders of men themselves. “Women can share in this healing process,” she writes. “We can guide, instruct, observe, share information and skills, but we cannot do for boys and men what they must do for themselves. Our love helps, but it alone does not save boys or men. Ultimately boys and men save themselves when they learn the art of loving” (16). This collaborative paradigm or “partnership model” is inclusive but also allows for important differences in the roles and responsibilities that men and women enact in this process.

- hooks presents many excellent criticisms of feminism, most of them focusing on how feminism has failed to acknowledge the pain and suffering––often self-imposed––that men experience under patriarchal domination. Given her position as a prominent figure in the modern feminist tradition, this capacity for self-critique is healthy and refreshing.

- The Will to Change offered many opportunities for me to reflect on the ways I have been able to nullify or minimize the negative impacts of patriarchy on my own life, as well as the ways I have caved to certain patriarchal pressures. hooks’s assessments of men’s successes and failures are as humbling as they are empowering, and they helped me become better-acquainted with my own perspectives and subtle biases.

- I did discover several important points of personal disagreement with hooks’s outlook. I think she’s too comfortable treating patriarchy as the sole cause of male disconnection and destruction. Her narrative of patriarchy can be so totalizing that it doesn’t leave enough space for other causal factors, especially biology and evolutionary psychology. I have no doubt that patriarchal culture plays a major role in shaping the thoughts and actions of men, but I also think a significant portion of male violence, aggression, and social dominance behavior flows from our evolved animal natures. I don’t think these qualities are “hardwired” or guaranteed, but I do think the capacity for violence is present in almost all men (and women as well, perhaps to a lesser extent) due to biological reasons that may prove more resistant to changes in patriarchal culture than hooks seems to believe.

- I think hooks can fairly be accused of indulging in overgeneralization throughout the book. She readily drops broad statements such as “most people think…” or “almost everyone believes…” or “popular opinion says…” or “oftentimes men…” while never citing any hard data. The book contains many passages from other writers and occasional vague allusions to the findings of studies, but there’s not a single footnote, nor is there is list of notes or references at the end of the book. This chips away somewhat at hooks’s credibility and made me skeptical of some of her broader claims about how and why men (and people more generally) are the way they are.

- Another problem is that I found many of hooks’s critiques of popular media to be simplistic and unfair, sometimes to the point of absurdity. Her claim that “The Harry Potter movies glorify the use of violence to maintain control over others” couldn’t be less true, and she offers not a lick of textual evidence to support it (52). She also characterizes Harry himself as a “supersmart, gifted, blessed, white boy genius (a mini patriarch)” (52). Anyone who has read these books knows that Harry is a pretty average guy in most ways, except perhaps being unusually kind and brave. He’s not a great student, certainly not “supersmart” or a “genius.” The presence of Hermione’s character––one of the great feminist figures of modern YA fiction and arguably the narrative’s “true” hero––in part shows that Harry needs an actual genius in his friend-group in order to survive the many attempts on his life during his years at Hogwarts. In addition, Harry rightly attributes much of his own success to pure luck, demonstrating humility regarding his own limited capacities. I certainly don’t think the HP stories are perfect or undeserving of criticism, but hooks’s particular attack on this series is indefensible.

- Finally, I think hooks’s arguments in favor of “feminist masculinity”––compelling as they may be––face an insurmountable branding problem. Given the variety of male experience and the diverse challenges associated with getting us to unplug from patriarchal norms, the language we use to pitch an alternative route to male flourishing really matters. The pragmatic truth is that many, many men are never going to accept an ideological label that makes claim to their masculinity by leading with the word “feminist.” I think “new masculinity” or “positive masculinity” are much more appealing, but my favorite option is “humanist masculinity.” This last option is appropriately universalist and syncs nicely with hooks’s excellent observation that “selfhood, whether one is female or male, is always at the core of one’s identity” (117).

Favorite Quotes:

Only a revolution in values in our nation will end male violence, and that revolution will necessarily be based on a love ethic. To create loving men, we must love males. Loving maleness is different from praising and rewarding males for living up to sexist-defined notions of male identity. Caring about men because of what they do for us is not the same as loving males for simply being. When we love maleness, we extend our love whether males are performing or not. Performance is different from simply being. In patriarchal culture males are not allowed simply to be who they are and to glory in their unique identity. Their value is always determined by what they do. In an antipatriarchal culture males do not have to prove their value and worth. They know from birth that simply being gives them value, the right to be cherished and loved. (11-2)

We need to highlight the role women play in perpetuating and sustaining patriarchal culture so that we will recognize patriarchy as a system women and men support equally, even if men receive more rewards from that system. Dismantling and changing patriarchal culture is work that men and women must do together. (24)

Patriarchy promotes insanity. It is at the root of the psychological ills troubling men in our nation…Patriarchy as a system has denied males access to full emotional well-being, which is not the same as feeling rewarded, successful, or powerful because of one’s capacity to assert control over others. To truly address male pain and male crisis we must as a nation be willing to expose the harsh reality that patriarchy has damaged men in the past and continues to damage them in the present. If patriarchy were truly rewarding to men, the violence and addiction in family life that is so all-pervasive would not exist. This violence was not created by feminism. If patriarchy were rewarding, the overwhelming dissatisfaction most men feel in their work lives…would not exist. (30-1)

The first act of violence that patriarchy demands of males is not violence toward women. Instead patriarchy demands of all males that they engage in acts of psychic self-mutilation, that they kill off the emotional parts of themselves. If an individual is not successful in emotionally crippling himself, he can count on patriarchal men to enact rituals of power that will assault his self-esteem. Feminist movement offered to men and women the information needed to challenge this psychic slaughter, but that challenge never became a widespread aspect of the struggle for gender equality. Women demanded of men that they give more emotionally, but most men really could not understand what was being asked of them. Having cut away the parts of themselves that could feel a wide range of emotional response, they were too disconnected. They simply could not give more emotionally or even grasp the problem without first reconnecting, reuniting the severed parts. (66)

The men who choose against violence, against death, do so because they want to live fully and well, because they want to know love. These are men who are true heroes, the men whose lives we need to know about, honor, and remember. (74)

Today’s male worker struggles to provide economically for himself. And if he is providing for self and family, his struggle is all the more rigorous and the fear of failure all the more intense. Men who make a lot of money in this society and who are not independently wealthy usually work long hours, spending much of their time away from the company of loved ones. This is one circumstance they share with men who do not make much money but who also work long hours. Work stands in the way of love for most men because the long hours they work often drain their energies; there is little or no time left for emotional labor, for doing the work of love. The conflict between finding time for work and finding time for love and loved ones is rarely talked about in our nation. It is simply assumed in patriarchal culture that men should be willing to sacrifice meaningful emotional connections to get the job done. No one has really tried to examine what men feel about the loss of time with children, partners, loved ones, and the loss of time for self-development. (94)

When men practice integrity, they accept that part of the work of wholeness is learning to be flexible, learning how to negotiate, how to embrace change in thought and action. The ability to critique oneself and change and to hear critique from others is the condition of being that makes us capable of responsibility. To be able to respond to family and friends, men have to practice assuming responsibility. (164)

The work of affirmation is what brings us together. When men learn to affirm themselves and others, giving this soul care, then they are on the path to wholeness. When men are able to do little acts of mercy. They can be in communion with others without the need to dominate. No longer separate, no longer apart, they bring a wholeness that can be joined with the wholeness of others. This is interbeing. As whole people they can experience joy. Unlike happiness, joy is a lasting state that can be sustained even when everything is not the way we want it to be…

Men of integrity are not ashamed to serve. They are caretakers, guardians, keepers of the flame. They know joy…This is the true meaning of reunion, living the knowledge that the damage can be repaired, that we can be whole again. It is the ultimate fulfillment that comes when men dare to challenge and change patriarchy. (166-7)

We read self-help books that tell us all the time that we cannot change anyone, and this is a useful truism. It is however equally true that when we give love, real love––not the emotional exchange of I will give you what you want if you give me what I want, but genuine care, commitment, knowledge, responsibility, respect, and trust––it can serve as the seductive catalyst for change. (177-8)

The root meaning of the Latin word patior or is “to suffer.” To claim passion, men must embrace the pain, feeling the suffering, moving through it to the world of pleasure that awaits. This is the heroic journey for men in our times. It is not a journey leading to conquest and domination, to disconnecting and cutting off life; it is a journey of reclamation where the bits and pieces of the self are found and put together again, made whole. (181)

Thanks for giving bell a shot, Miles. She has affirmed, humbled, and strengthened me in so many ways as I have attempted to make sense of what it means to “be a man” in this often confusing, violent, and ruthlessly competitive world of ours. I also appreciate your points of critique. Much love to you.

Thanks Jesse for putting this book on my radar! My journey into the philosophy and psychology of men’s issues is still just beginning, so I’m trying to cast a wide net in search of all the different frameworks that are available. hooks’s perspective is definitely valuable and I probably wouldn’t have discovered this book if not for you! 🙂

I really enjoyed this books overall thesis, and think that it works best when its points are directly related to building and supporting that thesis. However, the book loses its poiniancy in some of the specifics; it gives a rather flat and over generalized look at rap music for example, that plays into white supramacist narratives about the artform, rather than giving a solid well rounded critique of the artform that properly adresses the fact that it is by no means monolithic, and that a wide veriety of artists and expressions come through it. I also think that her small rant about anger is fairly weak and not well backed by actual psychology. Anger is not some emotion that should be repressed and removed from the human psychology, it is a important emotion that allows for one to adress when you are being mistreated by others. What you need to work on is what things make you angry, and how to healthily express that anger. Additionally, the purity culture based views on sexuality are weak. Women having the choice to express their sexuality how they wish to and without judgement is an objectly good thing, and she gets involved in shaming women for having sex in parts of this book that damages the authors credibility. I definitely agree with you about some of her media critique issues as well, often time fully flattening a movie or series and removing any nuance from its presentation to make it fit into her thesis better.

Thanks Edward for this thorough and thoughtful comment. Lots to consider here!

I just read the book and I also believe there are too many generalizations. Hooks seems to think that most households are like Ralph and Alice Kramden. If that were the case the book works. She mention how boys were raised to be violent while girls were taught to avoid violence. I’m a 57 year old black male and in my neighborhood everyone was taught to fight. Our people had been enslaved for 400 years, the world had already showed us that if you can’t defend yourself, you might be made a slave. Patriarchy is a problem, but most times if I hear men and women submitting to a 1950’s model of gender identity, they are religious. For this group we can’t eliminate patriarchy without them feeling like its an attack on their religion. This is a big issue. I can’t believe that after 188 pages of writing Ms Hooks was never able to say anything about the role religion plays in Patriarchy. She could have started with God making Adam and Eve. If the Supreme Being realized by making Adam alone and to fix the mistake he made Eve, as soon as god took Adams rib to make Eve, the second mistake was made. That passage in the bible is the underpinning of male dominance over the last 2000 years.

Hi Chuck and thanks for this thoughtful comment! I don’t have a lot of religious influence in either my personal background or intellectual training, so haven’t thought in much depth about the connection between religion and patriarchy. But as you mention the link does seem both obvious and quite strong. This gives me something new to consider and learn. I appreciate you sharing your valuable perspective! 🙂