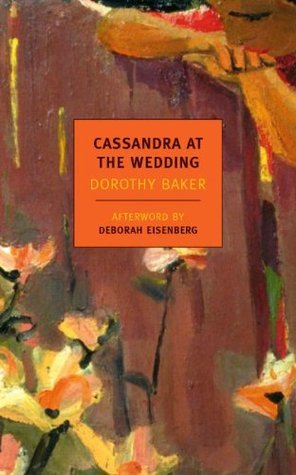

SNQ: Dorothy Baker’s “Cassandra at the Wedding”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

Dorothy Baker’s Cassandra at the Wedding is a captivating work of 20th century fiction. The narrators are identical twins––Cassandra and Judith––who return home to their family’s ranch in California to celebrate Judith’s wedding. Most of the story is told from Cassandra’s point of view, revealing her fraught internal conflicts over what her sister’s imminent marriage means for their relationship. Over several days, Cassandra and her family members confront their ambivalent feelings about one another, events in their past, and possibilities for the future. They engage in tense conflict and also experience tender moments of understanding and forgiveness. Presented in beautiful, surprising prose and steeped in psychological complexity, Cassandra at the Wedding is a harsh but rewarding novel that invites readers to explore the depths of human isolation as well as the peaks of meaningful connection.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- It’s been a while since I read a proper literary novel, and it was such a breath of fresh air! Baker’s language is delightfully precise, the story is emotionally riveting, and there are a host of excellent metaphors and allusions to Greek Mythology. The book is also quite short, in a good way.

- The novel’s central theme is the tension between Cassandra’s passionate desire for individuation and her intense need for closeness. The book is replete with poignant descriptions of what it feels like to reject everyone around you in a desperate attempt to assert your own identity, only to then collapse from the weight of your own grandiosity when your extant need for intimacy inevitably announces itself. Baker dives deep into the psychological benefits and challenges associated with having an identical twin.

- Tying into this theme are Baker’s keen observations about the nature of addiction and mental illness. We learn about the seduction of addiction through the genuine release the characters get from substance use (primarily alcohol), but we also see how over-reliance on substances leads to dysfunction. Regarding mental illness, Cassandra provides a particularly salient example of how “all-or-nothing” thinking can prevent people from confronting reality and moving forward in the face of adversity. There is also a section told from Judith’s point of view that cleverly reveals some key disparities between what Cassandra thinks her family thinks of her and what they actually think of her.

- This novel contains some very powerful passages about suicide and death. While I think these are among the best parts of the book, readers who are sensitive to these topics should take note.

- While I thought the whole book was excellent, I especially liked the end. It felt hopeful without being unrealistic or insincere. This is a story of someone who is passing through the eye of an existential needle, and whose struggle wins her the possibility of peace and redemption on the other side.

Favorite Quotes:

I seldom get praised for the hard things I do, and I do some of the hardest things. Things like waking up in the morning and going to sleep at night, all all alone except when I’m with someone; and it’s getting harder and harder for me to be really with anyone. And more or less impossible, on the other hand, not to be frequently with someone. (33-4)

All I want out of life is to find something worth being serious about. Ask me if I can ever be serious, and the only answer is that it’s all I can be and all I ever am, have been, or will be. It’s my whole trouble, but it’s also my one certainty––to know how serious I can be about what I love. (94)

No one…can understand what it’s like to be bound to a way of life like ours––a situation we inwardly glory in, but one that we have to protect at every turn from the menacing mass of clichés that are thrust on us from the outside. To be like us isn’t easy, it requires constant attention to detail. I’ve thought it out; we’ve thought it out together. I’ve tried to explain to my doctor that it’s a question of working ceaselessly at being as different as possible because there must be a gap before it can be bridged. And the bridge is the real project. (100)

I don’t believe I recognized it as a thought at first, simply as the dim stirring of an instinct, an instinct for peace––cessation of hopeless hope, or call it a war to end all wars. It can’t be done on an international scale, too many embassies, go-betweens, attachés. But one single person––and now I felt very very single––can accomplish what he must face sooner or later anyhow––his own removal from the fray. It doesn’t even take courage, because you don’t give up anything if you have nothing left to expect. You bow out with dignity, looking presentable, newly bathed, scrubbed up, combed out. They can tell you planned it because the whole thing is so immaculately, so to speak, conceived. And there will be deep gratitude on all sides, and on the part of some––regrets laced with admiration. (134)

So much for the passing in review. It was quick, I think––a great deal of it but soon finished, and then, though it’s not simple, or even sensible, to try to reconstruct nothingness, I believe I almost achieved it for a while––a great stretch of purest black velvet, smooth, soundless, the very piece of black velvet I’d been looking for for so long. I can remember feeling it drop, weightless, over me, swathing and swaddling me and then becoming one with me so that there was no way to tell which was velvet and which was Cassandra. But I never made it all the way to nowhere; there was a dogged spark of consciousness, very small, very feeble, but dogged, and it could just as well be called conscience, dammit, as consciousness, because I knew in some beating depth that I was engaged in illicit communion with the one great howling beauty of them all, and that there would have to be what there always has to be in this kind of affair––repercussions. There would be jealousy, accusations, recriminations, the full deck of threats and noises. I couldn’t stay all night, I’d have to leave by an inconspicuous exit and try not to kick anything over on the way out, and remember to pick up my things––my bag, my lipstick, all marks of identification, including the ostentatious monogrammed items my friends are forever giving me. Collect them and leave without lingering, because nobody will bless this union, not even granny, who will bless practically anything if you set it up right. No chance for me and the one of my choice, my calm sweet quiet black-velvet love––no receiving line, no friends to wish us all the happiness and success in the world in our new life, which of course is the wrong word, but how would they know enough to believe I could prefer the opposite number? How could they, when the best thing they can think of is life? And wish you all success and happiness in it, unless they happen to be tipped off that you want to marry a bolt of black velvet and you like it that way. Then they don’t wish you anything; they shake their heads, they pity you, they say you jumped the gun. Cassandra Edwards took her own life, because the headlong fool could not quiet down and wait for a natural cause. (196-7)

The things that get in your way, the indignities you have to suffer before you’re free to do one simple, personal, necessary thing––like work. If it has to be a quarter inch thick you hock a guitar, and when the supply runs out, hock something else, and no matter what you have to part with to do it you hang on to the hope of painting a good picture someday. And in time, others. That’s painters. But for me it was pretty much the same thing. I could never write any of this until I could tear up the pawn ticket on the ghost of my mother. It’s a different order of hocking but it comes to the same thing. Don’t lean. Stand up. Find a way. (225)