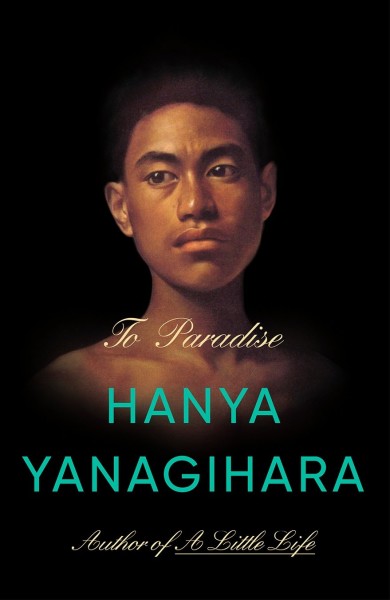

SNQ: Hanya Yanagihara’s “To Paradise”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

Hanya Yanagihara’s To Paradise is an exquisitely-crafted and emotionally-gripping novel that covers a huge swath of thematic, historical, and futuristic ground. The story is told in three Books, each of which is loosely connected through the recurrence of certain character names and relationship dynamics that inhabit a single home in Washington Square, New York City. Book I takes place in 1893, and invites the reader into an alternate history in which the American Civil War had much different consequences. Book II takes place in 1993, and explores the true-history HIV/AIDS crisis and the Hawaiian sovereignty movement. Book III takes place in 2093, and depicts an America that has devolved into a grim totalitarian dystopia in order to stave off a combination of increasingly-deadly pathogens and climate catastrophes. These stories appear to take place in separate but metaphysically-linked universes, but the novel is highly interpretable on many levels. Brimming with brutal brilliance and humanistic heart, To Paradise is a tour de force of literary creativity that solidifies Yanagihara’s place among today’s most elite and daring novelists.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- The novel toys with character names and identity across three centuries in a way that feels genuinely innovative, including clever and subtle elements of metafiction. It’s an ingenious narrative embodiment of the old saying that “history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

- Readers can expect the same psychological density and intensity of Yanagihara’s two other novels, A Little Life and The People in the Trees. While To Paradise covers a lot of dark territory (especially in the third Book), it is not nearly as punishing as A Little Life. It is also much more ambitious compared to her previous works; Yanagihara took a bunch of risks with this book, all of which paid off in my opinion.

- Yanagihara displays masterful building of romantic and sexual tension throughout the novel, but especially in Part I. She shows how romantic relationships help us learn that we are capable of giving and receiving love, and also delves into the deep fear of betrayal or abandonment by those closest to us.

- The book contains numerous show-stopping passages about the nature of love, connection, death, grief, and regret.

- Yanagihara spends a lot of time considering the psychosocial effects of class and racial divisions, including the harsh legacies of slavery and colonialism. In Parts II and III, she keenly depicts political radicalism as a psychological pitfall that can seduce young people, hijack their intellectual development, and obliterate their capacity for individual thought.

- Book III is a timely and absolutely terrifying extrapolation of current challenges brought about by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic. This includes incisive examinations of disease and resource management, the politics of media and (mis/dis)information, the ethics of science when millions of lives are at stake, and Orwell-level passages about dystopia’s philosophical underpinnings. Yanagihara demonstrates what it’s like to live in a dystopia as a relatively normal citizen, and also shares the internal experience of a well-intentioned scientist-turned-bureaucrat who consciously works to consolidate state power in the service of public health.

Favorite Quotes:

To live a life in color, a life in love: was that not every person’s dream?…True, his forefathers had fought and toiled to establish a land in which he was free, but had they not also ensured and therefore encouraged a different kind of freedom, one greater because it was smaller? The freedom to be with the person he desired; the freedom to place above all other concerns his own happiness. (127)

You should always have a close friend you’re slightly afraid of…Because it means that you’ll have someone in your life who really challenges you, who forces you to become better in some way, in whatever way you’re most scared of: Their approval is what’ll hold you accountable. (225)

What he wouldn’t know until he was much older was that no one was ever free, that to know someone and to love them was to assume the task of remembering them, even if that person was still living. No one could escape that duty, and as you aged, you grew to crave that responsibility even as you sometimes resented it, that knowledge that your life was inextricable from another’s, that a person marked their existence in part by their association with you. (231)

The world that we live in––a world that, yes, I helped create––is not one that will be tolerant of people who are fragile or different or damaged. I have always wondered how people knew it was time to leave a place, whether that place was Phnom Penh or Saigon or Vienna. What had to happen for you to abandon everything, for you to lose hope that things would ever improve, for you to run toward a life you couldn’t begin to imagine? I had always imagined that the awareness happened slowly, slowly but steadily, so the changes, though each terrifying on its own, became inoculated by their frequency, as if the warnings were normalized by how many there were.

And then, suddenly, it’s too late. All the while, as you were sleeping, as you were working, as you were eating dinner or reading to your children or talking with your friends, the gates were being locked, the roads were being barricaded, the train tracks were being dismantled, the ships were being moored, the planes were being rerouted. One day, something happens, maybe something minor, even, like chocolate disappears from the stores, or you realize there are no more toy shops in the entire city, or you watch the playground across the street from you be destroyed, the metal jungle gym disassembled and loaded into a truck, and you understand, suddenly, that you’re in danger: That TV is never returning. That the internet is never returning. That, even though the worst of the pandemic is over, the camps are still being built. That when someone said, in the last Committee meeting, that “certain people’s chronic procreation was welcome for once in history,” and no one reacted, not even you, that everything you had suspected about this country––that America was not for everyone; that it was not for people like me, or people like you; that America is a country with sin at its heart––was true. (588)

Data, investigation, analysis, news, rumor: A dystopia flattens those terms into one. There is what the state says, and then there is everything else, and that everything else falls into one category: information. People in a young dystopia crave information––they are starved for it, they will kill for it. But over time, that craving diminishes, and within a few years, you forget what it tasted like, you forget the thrill of knowing something first, of sharing it with others, of getting to keep secrets and asking others to do the same. You become freed of the burden of knowledge; you learn, if not to trust the state, then to surrender to it. (633)

I know that loneliness cannot be fully eradicated by the presence of another; but I also know that a companion is a shield, and without another person, loneliness steals in, a phantom seeping through the windows and down your throat, filling you with a sorrow nothing can answer. (676)

Cobras are very fierce…Small, but quick, and deadly if they catch you…A mongoose can actually kill a cobra, if it wants to––but they very rarely do…It’s too much work. So they just respect each other. But we’ll be a cobra and a mongoose that do more than just respect each other: We’ll be a cobra and a mongoose that unite to keep each other safe from all the other animals in the jungle. (700)

heard some similarly good reviews and also her interview on NPR, it was really good. I look forward to reading this…

in 2027

Cool! You will love this one whenever you get around to it. 🙂