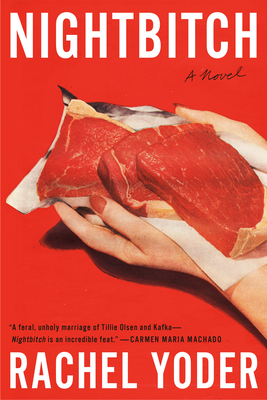

SNQ: Rachel Yoder’s “Nightbitch”

by Miles Raymer

Summary:

Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch is a work of magical realism about a woman who develops the bizarre habit of transforming into a dog and leaving her house to hunt small animals at night. Frustrated with the challenges of mothering her young son and the lack of support from her amiable but largely-absent husband, the “mother” (or MM––we never learn her actual name) assumes the alter ego of Nightbitch in order to cope and explore new modes of self-care and personal growth. Nightbitch is a surprising work of 21st-century feminism, one that deftly parses the modern experience of female domesticity and pushes back against social norms in a way that is both innovative and satisfying.

Key Concepts and Notes:

- Yoder does a great job of depicting the ambivalence of parenthood, demonstrating how it can be both a claustrophobic nightmare rife with suffering as well as a potential source of self-validation and flourishing. This book effectively puts the lie to the toxic message that “working moms can have it all if they just try hard enough and have the right attitude.”

- In the sections where the mother turns into a dog, Yoder’s depictions of animal violence and sensory perception are riveting. She really captures the sinister side of animal instinct, along with the unfettered joy of learning to trust your emotions and questioning your sanity as a path to identity formation. She also links these concepts up with art theory in a smart way.

- The book also contains engaging plots threads that examine female friendship and feminist mythology. The mythological and magic realism elements invite the reader to question the limitations of science and rationality without indulging overmuch in anti-science or relativistic sentiments.

- Yoder’s writing isn’t consistently impressive, but certain passages in this book are fantastic.

- I am definitely not Yoder’s target audience, and as such had a difficult time warming up to this novel. However, I liked it more and more as I read on, and found the ending to be delightfully weird and emotionally rewarding. I was worried for a while that Nightbitch would amount to nothing more than a whiny screed about the confines of contemporary mother- and wife-hood, but it turned out to be a lot more nuanced and fun.

- My one lingering criticism is that I was pretty uncomfortable with the way Yoder portrayed Nightbitch’s husband for almost the whole book. She presented him as a two-dimensional combination of cliches––the hard-working-but-emotionally-unavailable man meets the clueless-male-enforcer-of-the-evil-patriarchy. He didn’t feel very believable to me, especially in contrast to the thoroughly-developed internal life of the mother. Fortunately, Yoder threw some minor character development his way toward the end of the novel, so I was happy with where he ended up.

Favorite Quotes:

That single, white-hot light at the center of the darkness of herself––that was the point of origin from which she birthed something new, from which all women do.

You light a fire early in your girlhood. You stoke it and tend it. You protect it at all costs. You don’t let it rage into a mountain of light, because that’s not becoming of a girl. You keep it secret. You let it burn. You look into the eyes of other girls and see their fires flickering there, offer conspiratorial nods, never speak aloud of a near unbearable heat, a growing conflagration.

You tend to the flame because if you don’t you’re stuck, in the cold, on your own, doomed to seasonal layers, doomed to practicality, doomed to this is just the way things are, doomed to settling and understanding and reasoning and agreeing and seeing it another way and seeing it his way and seeing it from all the other ways but your own. (7)

Having a baby did not, in any way, represent a departure from work to which a woman might, theoretically, one day return. It actually, instead, marked immersion in work, an unimaginable weight of work, a multiplication of work exponential in its scope, staggering, so staggering, both physically and psychically (especially psychically), that even the most mentally well person might be brought to her knees beneath such a load, a load that pitted ambition against biology, careerism against instinct, that bade the modern mother be less of an animal in order to be happy, because––come on, now––we’re evolved and civilized, and, really, what is your problem? Pull it together. This is embarrassing. (29)

How many generations of women had delayed their greatness only to have time extinguish it completely? How many women had run out of time while the men didn’t know what to do with theirs? And what a mean trick to call such things holy or selfless. How evil to praise women for giving up each and every dream. (161)

This must be what it means to be an animal, to look at another and say, I am so much that other thing that we are part of one another. Here is my skin. Here yours. Beneath the moon, we pile inside the warm cave, becoming one creature to save our warmth. We breathe together and dream together. This is how it has always been and how it will continue to be. We keep each other alive through an unbroken lineage of togetherness. (230-1)

Life unfolded through mystery and metaphor, without explanation. (238)